Skipping along

Skipping is the week’s theme, following the inadvertent use of the term by the Fed Chairman, along with the rather weird behaviour of Jeremy Hunt.

Although any skipping seems unlikely soon, on this side of the Atlantic.

The dear old ‘recession’ still lingers, unseen but feared, like an ex Prime Minister. We are convinced it will arrive, but as a ‘technical’ recession only. It should be hard for anyone to be surprised. Labour markets are much stickier and far more fragmented. Supply is short, so any systemic shock feels unlikely. While as old hands keep noting, single figure mortgage rates, well below inflation rates, are hardly restrictive.

Chair Powell (almost) mentions ‘skipping’.

Jerome Powell was bowling along contentedly, when he suddenly described the Reserve Board’s June inactivity as ‘skipping’. Although it actually was just a ‘skip’, before he realised the error and with a guilty look speedily reverted to the far more passive ‘pausing’. But we knew how he was thinking. He was going to keep his foot on the neck of borrowers for a bit longer – interestingly, he refers to real rates of interest, as somehow unjust and injurious. Odd that when asked anything about fiscal policy he instantly plays the neutral, technical banker, no good and evil there.

Moves in the real economy.

So, what has really happened?

Not a lot, energy prices have climbed all the way up, and now slid all the way down. Aggressive fiscal stimulus continues, any chance Biden has to bribe the electorate with their own money, he still takes. Employment remains strong, although there is some tightening in hours worked, but it is still pretty hard to see how the Fed gets down to 2% inflation for a year or two.

And yet, markets by a mix of that unseen recession and faith in so called base effects, do think inflation by the autumn, will justify a real pause. No skipping.

UK Chancellor’s odd statements

Here in the UK Jeremy Hunt is in quite a different place. Inflation still looks high and embedded, but he has carefully outlined how he would keep going with substantial hand outs to offset inflation (aka fiscal stimulus).

However, inflation control was all for the Bank to sort out.

This is nonsense, of course. The UK Government is yet again stoking inflation while taking no responsibility for stopping it. He then gave a tortuous explanation as to why his policies have now produced exactly the same interest rates as the Truss typhoon, created by his reckless predecessor, but somehow, not at all the same.

Rate rises – a global feature.

Funny that, as we noted at the time, there was little odd about the October rate spike, and much that the Bank could have done (but refused to) by a prompt rate rise (matching the US) to stabilise the currency and inflation.

Rate rises are a global feature, with not a lot one small country could do about it.

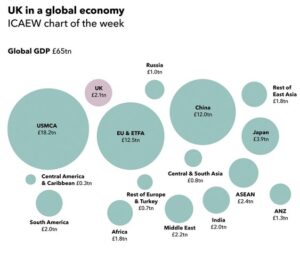

2021 chart produced by the UK Institute of Chartered Accountants

So quite where the virtue of the Truss toppling quarter point rise is now, is rather unclear.

As sterling shows, the prize for that autumnal sloth will be higher rates (and inflation) than elsewhere for longer. The thing about fire fighting is the sooner you start the less you have to do.

So how did Monogram’s methodology work?

Our in-house model switched into Japan in December 2022 and Europe in March 2023. As we only ever deal in half a dozen big global index Exchange Traded Funds, this is not a tickle, but 25% of the total equity position in (or out) at once.

Brutal and scary, but effective.

We look at the signal, kick the tyres, thump the bonnet, turn it off and on again, look for reasons to ignore it, and then six months later look back in wonder and say, “oh yes, that was right”. These signals are delicate enough to very seldom feel right at the time, but after almost a decade of running the model, we have learnt to obey.

So, our Momentum performance discussion, yet again, is about how much we made, not about in which direction the money went. While the GBP version, seeing similar signals, has also never come out of the S&P 500, which for a good while also felt wrong, but it seems was right, taking a long view. The USD model was more skittish but is back in both (S&P and NASDAQ) US indices now.

So, we do know where momentum has been, and it is quite strong.

Markets in the political timeline

The rational thinkers say the market is (still) too expensive, but the trend followers don’t agree, who is right?

We tend to feel just as Central Bankers were very slow to spot inflation, they are possibly being too slow to see it has now been contained, and the US skip may be a pause and then a snooze. Which would be very convenient for the Fed during the US Primaries, allowing for cuts into the US election?

Related to that, we watch with amusement a dialogue about the attractiveness of stock exchanges, in particular in London, couched entirely in terms of what potential listing companies say they want. Not a mention of what investors want, as if they just don’t matter. Quite absurd, as what all listings need is a deep market, good liquidity, stable tax regimes, and an attractive base currency.

Is London aiming to provide these? We seem to favour founders – so, tweaks to voting rights, smaller free floats, fewer shareholder rights. But then oops! No buyers.

This is worse than nonsense, it damages what little is left of London’s reputation. In this market you start with the buyers. The price performance of many a recent IPO spells out the problem, the sellers are finding it too easy to deceive people – a call is needed for greater transparency, longer lock-ins, and less pandering to insiders and their advisers (not more).

The Sleep of Reason

Big picture risk assessments today, and worries about the prevailing style of regulation - we look at where the next bank blow up maybe. We’re assuming this will again be caused by regulators and their herding behaviour. On the upside, an improving medium-term market outlook. Also, dollar danger.

But before I begin…

First of all, many thanks to those who replied to our sentiment survey, you are a cautious crowd! Over half (53%) sitting on the fence, alongside us. The largest directional group is bullish on equities (18%), but it is a pretty even bull/bear split with bonds, and quite a few equity bears too.

Regulatory Myopia and Declining Banks

Bank boards (and auditors) are still clearly confusing regulatory approval with sound banking, in the odd belief that excuse will wash, when they implode. In particular we worry about the vast amount of debt that is sitting on bank balance sheets, at below current market levels, and not in this case issued by governments.

We have notable anxiety about two areas, fixed rate mortgages and investment grade debt where, especially for the former, the numbers are vast. Perhaps the tightening steps to date appear so ineffective, just because so much of this old low-cost issuance, is only very slowly rolling off .

Big picture – the effect of long dated low-cost loans, with rising interest rates

This leaves cheap money in the system, funded by banks, that have to pay way more to keep funding these long-term deals. They’re doing this typically with short-term sources, like deposits. In sub-prime, asset finance, trade finance, consumer finance, none of it matters much, as they are pretty short duration. Which is where most people worry, because of default rates, we don’t.

But in mortgages especially the regulator typically issues the future economic scenarios to banks, who then price (originate) and provide for losses against that projection.

If that projection is absurdly few rate rises, for a decade (as it was till fairly recently), it seems banks just follow obediently along. As a result, they have issued vast amounts of long dated, low cost loans based on false or unrealistic assumptions.

Those regulator driven economic assumptions/scenarios are key, and yet are lost in the detail. Each bank has to publish them if you dig deep enough. (Some are on p155-157 of the HSBC accounts, for example, if you have the stamina.)

Re-mortgages – what they contribute to our big picture

The other part is refresh rates, in a falling interest rate world, borrowers re-mortgage every few years, but in a rising one early redemptions virtually stop. So, the whole system gums up, without fresh liquidity. Regulators have not seen, and have no data, on such a ‘higher rates for longer’ world. So, it is assumed that world cannot exist. While the key thing (still) on these scenarios is that interest rates are still assumed to be like rockets, straight up straight down.

Now if you assume that, there is some short term pain, but normal service resumes soon enough with no long-term issue. But is it realistic? It is a vast slow moving market as in this publication of the FCA’s mortgage lending statistics .

Inevitably the scenario dispersion used is small, indicating a regulatory finger remains on the scales. So, most banks take the Central Bank forecast as the middle way, with say 10% either side. All as at the historic balance sheet date. Last year they were nonsense even before publication, two months on.

That is aside from Hong Kong, where real economic models, with real outcome ranges are visible. For most markets you see a skein of twisted rope drifting laconically into the future, but on HK they produce an exploding ammunition graph, smoke trails looping everywhere.

To a lesser extent BP debt (a classic investment grade, big, global borrower) is a similar problem. It has half fixed, half floating issuance, but the fixed is at 3% with a fourteen-year average term and the floating at twice that, at 6%. Now someone holds that fixed debt, and if regulated it will have to now be held below par. Are BP going to prepay it? Despite the roar of cash coming in, why would they? It is stuck, unusable for 14 years, unless inflation (and rates) collapse as fast as predicted.

What else is driving markets?

The big upside drivers to us are, the end of COVID, the end of the energy spike and falling rates. The first two will help through 2023 and 2024. Rising rates are still hurting, but again 2024 and beyond looks good.

While the biggest current downside driver is the recession, which will impact 2023, but again rebound in 2024. So, the issue is: will the rather timorous monetary tightening and anaemic reductions in the absurd fiscal overdrive, be enough to defuse all that good news coming in the next year?

Markets apparently think not.

We are particularly struck by the NASDAQ up 18% year to date, yet our tech bell weather share, Herald Investment Trust (HIT) is still (marginally) down YTD. So is this a bitcoin-type story (all about liquidity) or is it based on tech fundamentals? If the latter, then why is it seemingly glued to the US, and not translatable? Even failing to reach non-US holders of US companies.

For now, until the price of global tech shifts, I treat the US as a special case; growth is not back yet.

While the currency charts are unclear, it does also feel like the beginning of the end of the great dollar story, with sterling persistently ticking higher of late.

From: this page published by the NY federal reserve.

From: this page published by the NY federal reserve.

That’s a real danger for portfolios that thrived on dollar power last year.

We close wishing you a happy Easter break. We will be back with St George.

A RIGHT OLD TONKIN

About Influence – American and Russian, mediated by the Chinese

So, to start with what does worry us: That is the slide to a hot war with the powerful Eastern autocracies, fueled by the EU with Napoleonic tendencies, an old man in the White House and a curious sense of ‘crusades’ with no consequences.

For those with long memories of American imperialism, the latest drama even fits neatly as a modern Gulf of Tonkin, a key moment in the slide to war. In that case (south of Hanoi) the clash was naval not aerial but was still notable as one directly between the warring parties and not just their local proxies.

While elsewhere the pieces move, China can not let Russia fail, nor descend into chaos, their long-shared border must stay intact and secure. They no more want the US there than the Russians do. The first step after his confirmation as ruler for life, by Xi, was indeed to go to Moscow.

And the bitter battles in the Middle East of Persian against Arab, Sunni against Shia have cooled abruptly, under Chinese influence. The world once more understands that the US is the threat to peace and stability, not just their fractious neighbours.

For Biden it is an easy fight, the Pentagon so far has played a blinder, what can go wrong? While, for now, France is Europe, no other large state has anything like their stability, Italy is led by the unspeakable, Germany has free market liberals in a bizarre ruling alliance with Greens, Spain is wrapped in its own forthcoming general election, the UK both distinctly detached and under a caretaker government.

The UK budget said nothing, incidentally.

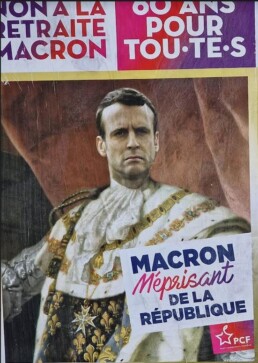

Main influences in France.

While the left in France, as the above photograph shows, are very alive to Macron’s ambitions, to add more territory to the EU, arrange more protectionism for French goods and to suck the labour force out of adjacent states to serve the Inner Empire. Just like Bonaparte tried (and failed) to do, with dire consequences for the French nation.

For all that, the domestic fracas in France (which makes our own strikes look rather tame) was inevitable. Raising (by not a lot) the pension age from 62 to 64, against our own 67 looks small, but it was a clear campaign pledge.

The absence of any minor party wishing to self-destruct, by supporting it in the French legislature, is no great surprise either. So, he has implemented it by decree and Macron has dared the opposition to now either remove his prime ministerial nominee, or shut up.

Banking On Nothing

So, what of markets? Well, the end of SVB is no great loss, it had several policies that had to implode if rates rose, especially on the lending side. It was painfully ‘woke’; I can tell you more about the Board Members sexual orientation, gender and ethnicity than their banking experience, the former just creeps into the end of their latest Annual Report, the latter was invisible to me.

SVB’s long list of ESG triumphs and poses (and it is long) at no point included not going bust. It did commit an extra $5billion to climate change lending, which I guess has all gone up in smoke now. Still apart from all being fired, the bank insolvent, the remnants rescued by the hated Washington mob, under investigation by the DoJ, all the rest of their “G” was superb, and so, so, cool.

I don’t see Credit Suisse as a danger, although it may be in danger. It has had an appalling run of misfortunes, with musical chairs at the top, but it remains a cornerstone of Swiss identity. To let it fold would be highly damaging and cause shockwaves in derivatives markets.

Influence on the markets

So, I do understand the Friday sell off (who wants to be weekend long with regulators on the loose). And we do understand markets needed to go down, after the big October bounce, indeed it was a key reason for our building up over 33% cash or near cash at the previous month end. We knew the winter rally was fake.

But I don’t see this as much more. Retest of the S&P 500 October low? It should not be. I take a lot of heart from bitcoin soaring (63% YTD); if liquidity was short, that would not have happened.

But for all that, I don’t like March in financial markets, too much is uncertain. So, this is more a time for cautious adding, rather than hard buying, but if we get to Easter (and hoping to be wrong on the Tonkin analogy) it does seem a better prospect.

Nor do I see how the various central banks can justify a pause in rate rises, at this point, but nor will they go in hard, that would be folly.

This Fed has made enough mistakes already.

Caution: Bumpy Road ahead

Puzzle: World markets have whipsawed in the last few weeks, from high anxiety to an almost beatific calm. The VIX volatility index has dropped to pretty well a post-pandemic low. Which should mean we all agree, but on what exactly? Rising inflation, yes, but how durable, and caused by what?

And that, we all accept, will make interest rates rise, yes, but how high for how long? Markets we feel are, to say the least, fragile.

At the turn, we know that moves can be dramatic both ways, for markets.

Are we really seeing a labour shortage? The UK truck drivers’ situation

What we see now is not a labour shortage, and hence political talk of stemming migration and higher wages is well off target. What it is, in part at least, is a failure of the routine operations of an incompetent government, something politicians typically don’t want to discuss.

The government has insinuated itself into so many areas, with its complex regulations, that the market economy now lies ensnared in myriad interlocking regulations, backed up by a deeply entrenched blame culture (and its friend the compensation economy).

To take one example, there is no shortage of truck drivers, but there is a shortage of qualified, approved, signed off and regulated truck drivers, because as part of the destructive lockdown, the government just halted the conveyor belt of required testing and approvals.

Truckers’ wages have for long been too low, of course, especially for the owner drivers in the spot market. What we have is not a labour shortage, it’s a paperwork shortage. The difference is vital for how enduring inflation is. A new driver will take a couple of decades to grow, but clearing a paperwork jam, a few months. One is enduring, the other transient.

Withdrawal of older workers from the labour market

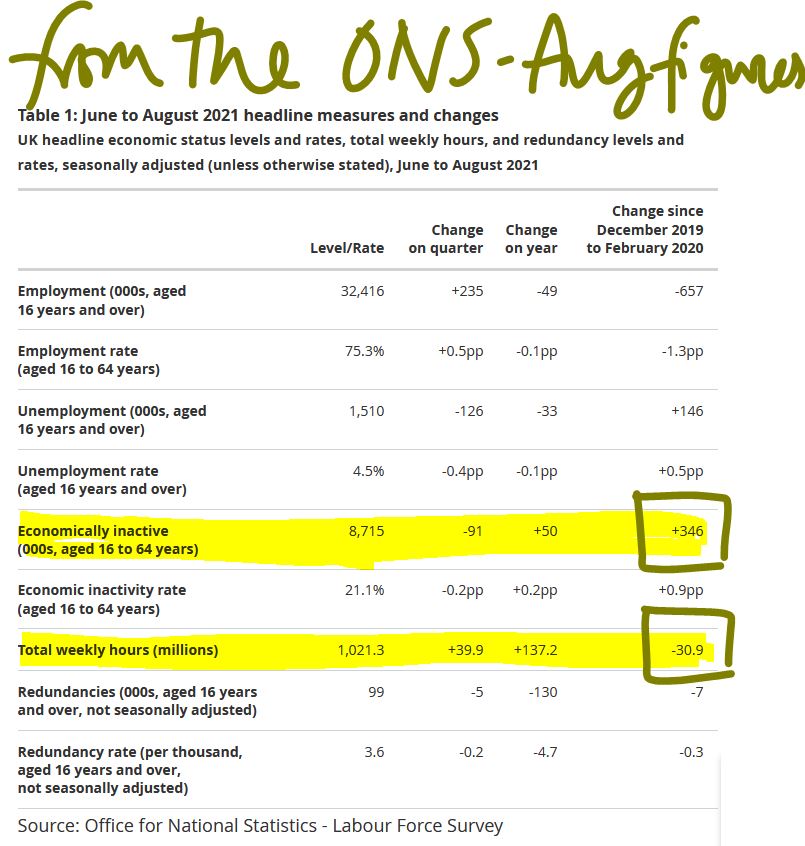

Work after all is something of a habit: once it is lost, it can be hard to understand why it existed. So, we see a marked increase in older workers in the UK who have just withdrawn from the market (Some thirty million fewer hours worked - see figure below). That too is not a labour shortage as such, they all still exist.

But if work was of marginal benefit to the worker, and the costs to resume work (actual or psychological) are high, disruption will cause the fringe or marginal job to be unfilled. Yet again more in the transient column than permanent.

Someone will waive the rules, or the government will notice, well before all drivers get paid high enough wages to cause embedded inflation. In any event articulated fuel tanker drivers tend to work for big employers, with good conditions, and are well organized. They have to be, after all they drive mobile bombs. The spot operator on a rigid rig is in a different market.

Inflation will most likely be transient

So, if it is not an actual labour shortage, it won’t cause wage inflation, and will be transient. Some other areas reliant on highly skilled older workers will continue to see standards fall, but generally younger workers will over time fill those slots and gradually acquire those skills. And it won’t be a long time.

Our view from way back was of 5% plus inflation and labour markets that struggle to clear this year. We were wrong to not foresee the failure of regulatory processes to keep up. However we still do see a permanently higher post COVID cost base and therefore in certain sectors, a large amount of marginal productive capacity are likely to be withdrawn from the market.

With a banking system that still struggles to offer commercial finance to the SME sector, because of excessive regulatory caution, there are swathes of jobs that have simply gone. So that labour will in time be redeployed. The current concern is that many of these workers show no desire, or ability under current conditions, to return to the market. But when they do, the capacity that has been destroyed will slowly return, and once more drive down prices.

Nor should we forget just how much the Exchequer loves inflation, as fiscal drag, their beloved tax on higher prices, smooths away so many budgetary blemishes. They will let it go, if they possibly can.

Commodity prices

On the input side we do still see commodity price rises as transitory, at least within the energy market. As others have noted much of that too is regulatory failure on a grand scale, not a true shortage. Price fixing by the state is a notoriously foolish concept, as we learnt in the 1970’s.

There are a number of other supply factors at play too, but while some will recur, most are temporary.

How long do we think the inflation spike will last?

So yes, inflation will spike, and yes it will stay elevated for much of next year, but no, we don’t see it as necessarily durable, once COVID restrictions and related behavioural changes vanish.

We are still pretty certain that the political costs of aggressive interest rate rises will outweigh any perceived price control benefit. As long as some Central Banks hold off rises, it will be very hard for others to do so, without sharp currency moves or bringing in formal exchange controls. That would in turn spook markets far more than rate rises.

The next phase of markets

All of this says to us that a major market dislocation, despite the benign signals, lies ahead in the next six months.

Markets shifting rapidly are more a sign of uncertainty than of a new degree of confidence, and we simply don’t trust it. We see inflation as apparently out of control, but no significant interest rate rise response is feasible. That can feel like stock nirvana, but also like investor purgatory, as you have no idea what is or is not a sustainable profit.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd