Where will the cards fall ?

The half year approaches - what has happened? Two very different quarters so far. And Investment Trusts complain too much, having stuffed their boards with placeholders with minimal stakes in the shares and multiple appointments. In markets many things still depend on how the cards (and ballots) fall.

THE FIRST HALF

With current interest rates for hard currency, high yield bonds, around 6%, you would expect riskier equity markets to be giving you over 10% a year, made up of a mix of capital and dividends. That’s the bar; it is quite high just now.

Looking back a year, only Japan and America comfortably achieve that, the S&P up +24%, NASDAQ up +30%, Nikkei up +14%. Germany creeps in at +10%, neither France nor the UK do. Outside developed markets, it is largely dire, only India at +25%.

Then looking just at the first half, all of Japan and Germany’s gains came in the first quarter, so they are now sitting well off their twelve-month highs. While as we know the big three, S&P, NASDAQ and SENSEX, are now close to all-time highs, they powered through the second quarter.

So, the challenge is, do they go on up, do the markets that have fallen back, after a good first quarter, come back to life, or do some of the dogs perform?

Some major markets, Friday close and intra day

I have no great faith in the UK market, nor in a new government being much better at growth (it can hardly be worse) than the current mob. But there are cheap looking international stocks in the UK and the punishment meted out to real assets, by interest rates and shrinking bank balance sheets, might be finally ending.

While quite clearly the good middle tier stocks are easily cheap enough to lure in bidders from abroad or private equity, in some number. UK valuations are in short OK, not something you can necessarily say about the US.

The residual underperforming markets do often have a nice yield, but who cares? With bond yields high and staying high, in an appreciating currency, why take a cut in yield in order to buy equities? Plenty of time for that later.

Anyhow in most European and Emerging markets, equities seem not to be able to get out from under their own feet, endlessly tripping over their own fractured politics.

INVESTMENT TRUSTS

We are hearing a lot of moaning about Investment Trusts, which the FCA really do not like. EU law always struggled with the trust concept anyway. That the FCA has shown no interest in freeing us from those shackles is not a surprise, it seems they too would rather channel money to Nvidia than invest in the UK. Here is their Lordships’ briefing on what EU rules we might be repealing. Nothing for Investment Trusts.

I am on balance on the Trust’s side, I do think closed end structures (as they all are) allow long term decisions, while protecting daily dealing, one of Europe’s quirky hang ups. Daily dealing is fine in deep markets, but an illusion in many medium and small equity markets. With liquidity ever more narrowly focused, closed end funds seem more, not less, important, for balanced capital allocation, competition and growth.

Trusts directors should also protect investors from over mighty fund management houses, who treat closed end funds with disdain, as captive funds, with often high fees. Their greed lets in low-cost passive competitors. Instead, their permanent capital should come with an obligation to hunt down good, index beating performance.

Sadly, the FCA has perpetuated a system, where the fund management house appoints the Boards, not, in reality, the other way round. So, they are decorative, good for marketing, and highly unlikely to fire the manager. Too many are industry insiders, serving on multiple trust boards, often in sequence. Seldom do they have an investment of at least their annual pay cheque in their current Trust, and often, little investing expertise in the relevant area.

So, Investment Trust boards hardly ever sack fund managers for poor performance. David Einhorn explains the bigger issue very clearly, noting benchmark hugging over time is what investors now get. There is a clear link to poor performance and bigger discounts, and to big discounts and treating shareholders badly: One area where big certainly does not mean better.

Rather than sabotage the sector with old, irrelevant EU law, the FCA should be hunting down poor performance, and making the “independent” directors just that, including banning directors shuffling around a set of one-manager trusts.

INTEREST RATES

We have just had Powell hold US rates, saying it is all data dependent, and slightly oddly he conceded the expectation is for a pick up in inflation, on the technical grounds that the abrupt drop in inflation last year, creates base effects.

Although he rules out more hikes; you get the feeling if he had held his nerve last summer, and added a bit more, inflation could be beaten by now. Not that he wants to or can add such instability now, so he is stuck, and we with him, watching paint dry.

With no real distress there is no pressure to cut prices, service inflation remains too high, energy prices are still quite strong, so no longer giving a deflationary boost. Both the AI boom and the resulting stock price gains, encourage consumer spending and keep (in most sectors) a strong labour market.

Markets are evidently OK with that, falling rates, no recession, growing earnings, is almost ideal. Meanwhile we are all hoping that Congress will keep either of the two old men from doing anything unusually silly, and the electorate will keep Congress on a tight leash.

Quite a lot of hoping and several months still to go.

DREAMERS

What would Trump’s high tariff isolationist world look like? What would the mirror image be in Xi’s China? Not now, not next week, but rolling into the next decade.

And whatever portfolio theory says, and whatever the optimistic investor believes, 80% of my own portfolio is flotsam, drifting up and down on Pacific tides. Stocks I both like and which have compounded over decades are remarkably few. Oh, and a brief word on African housing.

GOING IT ALONE

But first, to give it the grand name, autarchy, or self-sufficiency. A bit of a joke - the Soviet Union tried it, Iran tries it, China famously only revived after ditching it.

But it is back in fashion, and not just in strange places. The EU industrial and agricultural policy is starting to look like a version; beyond their four walls they need carbon and chemicals, but within them they don’t, nor will they allow imports of them (or products including them). Quite fantastic.

Trump is on his 60% tariffs line. Xi clearly wants to cut off foreign capital, as it arrives infected with democracy and transparency, and the associated foreign reporting or verification.

So, could they? Yes, the US could - it is big enough, can do most things, and largely trades internally. While at least in Trump’s imagination the commercial borders are sealed, and so enforceable.

What goes wrong? Well at some, quite distant, point people stop expecting to trade with the US. So, at its most extreme, if China can’t sell to the US, it won’t buy from them either. But that is decades away, most Chinese production can probably take a 300% tariff, and still sell at a profit.

The flip side of the tariff is the huge salary for a barista, or a trucker. The latter is not so far away. Prices of domestic US production must rise, to allow the blue-collar Mid-West to rejuvenate. US consumers of course (including that barista) will pay vastly more for US goods, or will get hit with the import tariff; this of course is a tax on them.

What about Xi? Well again it is possible - that’s how China ran for much of his life, with a lot of new infrastructure, industrialization, since installed. He can do it all again. There, unlike in the US, the issue is capital. As a big net exporter, an area that will itself be under pressure, money will be harder to find; it already is.

THE NIGHTMARE

Countries that go through this closing cycle typically also do default (as the Soviets did, as US (and UK) railways did,). Folly, but it can be done.

The US has been going down this route since Obama, Trump talked a lot about it, but Biden too sees the resulting wage inflation as a good thing. So, it is the next US President’s policy either way.

Obama was keen on hitting capital markets (FATCA was and remains both a non-tariff barrier (I am being polite here) and a tariff on external capital) and I suspect a Biden administration must do the same, to balance the books.

While Xi never really left protectionism, WTO and GATT were mainly honoured in the breach.

And Europe? There is quite a strong strategic need to expand to the East, although as that goes through (and we are talking the mid 2030’s here) Ukrainian farmers, like Polish farmers today, will buckle under the rules; it barely matters about the Donbas, the EU will shut those heavy industries down too.

So, I think autarchy can work for all three, it will support a large uncompetitive labour force, and consumer choice will vanish. In many cases there will be lower quality and high prices. All three will attack (or in some cases keep attacking) capital flows.

And in the end, the entrepots will survive, those not in any such block, like the UAE or Singapore today, Amsterdam in the 17th Century, Yemen under the Romans and Victorian Britain.

The winners will be flexible, a tad amoral, assertive, in fluid alliances, but reliant on gold not steel to survive. And they will suck in entrepreneurial talent too. At a strategic level, that feels the place to be looking. Although buying uncompetitive heavy industries before their brief period of tariff induced profitability, has a short-term allure.

DOGS OR GREYHOUNDS ?

The ludicrous halving of CGT allowances, based on some fantasy “yield” number from the equally ludicrous HMRC, via the OBR, means once again the tiresome process of harvesting losses is upon us. No longer can they sit unloved at the back, snoozing; out they must come.

And what a tale of dross they reveal, and scattered amongst them so many once “good ideas” and busted yield stocks. Well, it sticks in the throat, but perhaps sticking it in a US wonder stock for six months is better?

Of course, if I knew when I acquired them that the FTSE was moribund for two decades, I would never have bothered. Seems it is time to simplify.

COLLATERAL

And lastly African housing. It was one of Gordon Brown’s (and the PRA’s) great achievements to get UK banks out of overseas assets, far too volatile, currency? foreigners?- Who needs them? Bring it all home and inflate the UK housing market with safe, cheap, mortgages.

So, Citizens went, Barclays were hounded out of South Africa, and so on – although their post-sale performance has really not been great either. Africa now just does not have proper mortgage financing for the vast bulk of the population. This is at a level I had failed to fully comprehend.

You think that despite everything, Africa must have got better. But no housing, so less health, less stability, no financial security. Safe recycling of profits in the continent is still hard. Aid can’t create institutional reform, but that’s the need.

If you look for the breakout into developed status, it starts there.

All mimsy were the ‘borrowgoves’

Away from all the shenanigans with base rates and currencies, earnings seem to be showing a pattern. We look at the possibility of an unshackled NatWest and India’s renaissance after the Hindenburg disaster.

START OF EARNINGS SEASON

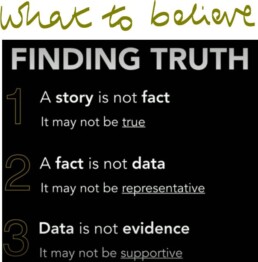

In so far as reported earnings have a pattern, it reflects the actual position, not the fears of a hidebound analyst community imprisoned by useless economic models. Statistics are not predictive.

There is no recession, whatever all those clever models predicted, never could be one with the extreme fiscal stimulus (quite unlike the private sector fuelled inflationary blow outs of previous downturns), high employment and plenty of liquidity. So, real life earnings are in a purple patch, high and in cases rising demand, with falling or stable costs.

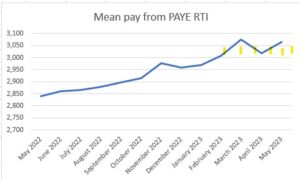

Meanwhile wage costs are perhaps stabilising and the labour supply position seems less frenetic.

In-house graph from published UK Government statistics – real time statistics

But dividends are generally ticking up, a nice bonus to collect when interest rates do start to fall next year, and valuations based on yields look low again.

FLAVEL OF THE MONTH

Nat West really is a sorry tale. The government stupidly sold off the crown jewels at give-away prices, and it now seems to be clinging on to the chaff for no good reason. The dead hand of the state permeates the place, and given the huge interest being paid on the vast national debt, surely a sale of all the government holding is long overdue.

You read the voluminous annual accounts and somewhere about page 180 the PR guff gives way to the reality of declining business lending, a worsening net promoter score and that ultimate civil service fudge, of combining two corporate departments to obfuscate.

Does NatWest actually dislike its customers?

I speak from experience – NatWest seems to dislike small business: we moved the last of our corporate accounts from there this year. Why? In striking contrast to the PR flim-flam that dominates the annual accounts, it seems that making life easy for us, is nowhere on their agenda.

At some point, it was just easier to go than fight – somewhere around the twentieth demand for the same details, and the endless Orwellian (“does not agree with other data”), even after the written confirmation that they were now content; so we quit. Always there was that threat to close the account, but not release our funds, for some arcane procedural reason.

I found the bloated pay packet for the CEO (and CFO) pretty hard to swallow for that performance. It just seems that they don’t attract good staff, and like the slow pacing of caged animals wearing their lives away, those that remain pick away at the residue of their customers.

As for valuation? Nat West would still be cheap, but I felt if it broke above £3.00 (as it did earlier this year) again, on present form – that’s not a terrible exit.

Let’s hope this starts a basic rethink and some real value creation.

RISING IN THE EAST

We noted when the Hindenburg short-selling started in India, and we doubted that it was much more than a clever speculator, despite the sad sight of the neo-colonial British press (and a few Americans) lining up to say “I told you so”.

Friday’s FT was discussing India and still called it “low-growth… dependent on commodities… hampered by political dysfunction and corruption”. Extraordinary – stale, lazy, stereotypical.

The reality is as we predicted: after a pause while stock markets looked for a systemic problem, and the short sellers booked their profits, the Indian market strode on to a new height.

From Tradingeconomics

Not that the biased UK financial press would ever mention that story. Far from the mud hut image they seemingly seek to portray, plenty of IPO (and deal making activity) is showing that India, not Europe is becoming the true challenger in high tech.

The SENSEX started this century at 5,209, the FTSE 100 started at 6,540. The FTSE 100 has made it to 7,694, and the SENSEX? It has powered past to 66,160. One is up some 18% in 23 years, (not enough to even cover advisor and custody costs), the other 1250% in the same time.

No sensible portfolio can have omitted India this century, but the UK press will have worked hard to ensure most UK ones still do.

Well, that’s the half year done, we will resume on the 10th September, expecting markets to be drifting sideways, but that gives plenty of time for the traditional summer bursts of excess or despair.

Although if it is performance you want, getting the big moves right, and the right markets, is far superior to the timing of most individual stocks.

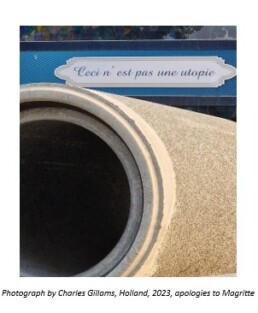

It is Not a Pipe

A long view this time : Has the price of capital changed for good? How bad is the UK position? Oh, and the unusual universality of colonialism.

A Far Off Galaxy

Let’s start with colonialism. I have been reading about the benighted past of Bulgaria (R.J. Crampton, 2nd Ed, CUP). A Bulgarian I know said that the country ‘has a knack for picking the wrong side’ - a little harsh, I thought. However, it has always existed as a colony, aside from a brief imperial phase around the last millennium but one, and before that when it equated to Thrace, almost as far back again.

Given the option, Bulgaria recently opted to join the Western European empires’ current formulation as the EU and NATO - the latter being the armed wing of Western thought. Bulgaria had suffered horribly under the Soviets, with a steady and ruthless coercion of an existing multiparty democracy, at a speed just enough to keep outsiders ignorant, or if not, passive.

That history gives me a whole new viewpoint, on the string of broadly similar states. The Balkans and The Middle East all appear in a new light, and indeed I start to comprehend the bitter sideshows (as they seem now) in both World Wars, over that same terrain.

The collapsing empires (Russian, Ottoman, Roman,) seem more influential than the current rulers in so many former colonial states. They are really not, as we think now, a series of nations fighting for ‘independence’. In most cases that independence is fragile to the point of being mythical, while the internal fissures are enduring. The cracks of nations within empires, not of states within a world.

Now You See It

One passage in Crampton’s work stood out “by mid-summer social and industrial unrest were widespread with strikes by civil servants. On transport networks, and despite the provisions of the law, in the ports and medical services. The government was forced to grant a 26% wage increase to all state employees, an action which weakened its attempts to control the budget deficit and inflation and which did little to impress the international financial organisations.”

Written about conditions just before another wrenching Balkan realignment last century, this rather made me stop and reflect.

A parallel with the UK?

Just how close are we in the UK to that edge? Lost in a warm feeling for individual strikers and their causes, and a very British willingness just to plough on, there still seems to be a real danger.

I am well aware of our great national strengths, in the arts, our language, higher education, science, heritage, even logistics and retailing - they are enduring causes for optimism. But long-term investors need to weigh up the recent damage, especially the loss of political capital by the “responsible” right, the high levels of debt and taxation, which coupled with low productivity, could also spell trouble, the certainty of ongoing nationalism and the unhealed rift of Brexit.

There is danger too in the probability of a Labour government, which however centrist the leader is, will have left wing factions to assuage. It is equally dangerous to continue our recent experience of minimal ministerial experience. I hope the change won’t be as bad as I fear, but it will probably be worse than I hope.

This remains a reason for the FTSE to be anchored to late 20th Century levels, despite almost every stock I research looking cheap. The fear of being still cheaper tomorrow rules.

Do Markets Care?

On the other hand, re-pricing capitalism after the decade of populist nonsense by central bankers does feel pretty good. If you have no cost of money and no reward for savers, financial gambling prevails.

All of this raises a key issue: is the apparent resurgence of speculation (the greater fool theory of investing) permanent? In which case investors should probably just watch momentum. Or is this most recent re-run of the last decade’s speculative phase, really transient?

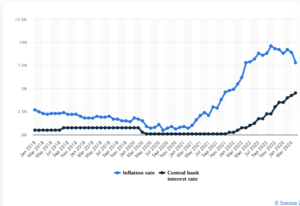

For a better view, see this page on Statista

As long as inflation exceeds the cost of money, assets will likely rise; the widespread return of real interest rates (a point we are almost at) should slow that down.

After that point what matters is cash flow, and whereas gambling will favour growth stocks, real returns come about when interest rates are high, but inflation is also falling. The gap matters and we are not there yet.

This is probably the crux of the next two years, and we doubt that having had a serene and slow drift towards recession, there is any reason either to expect a suddenly faster descent now, or really to expect the corollary, a sudden fall in interest rates, to offset a deep recession.

If rates stay high, but have indeed peaked and inflation declines, value investors should be in a better place. If they get it wrong, they are at least paid to wait.

As we have seen in the last twelve months, growth investors fuelled by borrowed money really do need a rising market, they get hit twice if it falls: both through a loss of capital and then the need to fund loss-making assets at real rates.

The Monogram View

Overall, our position has been that fundamentals should win, but we suspect momentum will win. Spotting the next momentum shift early, therefore remains a powerful driver of returns.

One narrative of 2023 (so far) is that the SVB crisis and stronger growth combined led to far more liquidity than markets expected. This fed into the gambling stocks, giving them momentum.

So, although the first half was not what we expected, the second half might still be. But it is just one narrative, and it may still be the wrong one.

Note : Further reading, for those interested in Bulgaria :

See also, The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Obolensky, Dmitri.

Pain delayed, pleasure denied

We look at the startling emergence of another US based tech bubble, the failure of value investing and offer some reflections on the UK market.

The Bones of World Financial Markets.

This has been a baffling half year in which, with few exceptions, we have ended up going sideways for most of it. The exceptions were in descending order, within equities, the NASDAQ (by a mile), Japan, Germany, the S&P and France. Although all, especially Japan, offset by a weakening local currency for UK investors. A quite unusual, largely unrelated, mix of old and new.

Overall, cyclicals in general, and energy in particular, as well as bonds, and China have been painful and financials at best so-so. It feels like a year to not hold what worked last year and vice versa. Nor is it as simple as growth versus value; neither have worked consistently, except in the case of a small (but rotating) group of tech stocks.

Our view thus far, has been that until global growth starts to move, we stay out of the way. This has been wrong, because the overvalued US mega stocks, were almost the only game in town. Yet jumping in now, of course, also feels very dangerous.

However, a few of our growth markers have, even if flat on the year, started to shift, not the highly speculative micro stuff, which is still falling away, but the solid middle ground. The hot India tech sector, far more connected to Silicon Valley than we realise, has suddenly jumped.

Macro Skeleton

What about the underlying macro story? Well, the pain of the invisible recession, and the pleasure of resulting rate cuts, have been delayed and denied respectively.

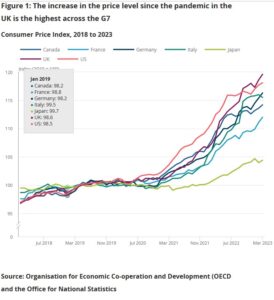

From the UK office of National Statistics – see this chart more clearly on this page.

From the UK office of National Statistics – see this chart more clearly on this page.

Well, there it is, poorly controlled inflation persists, a longer rate squeeze may still be needed. The vanishing China post-lockdown boom means that there was no sudden stimulus to offset that. Our published data (from Andrew Hunt) was saying Chinese ports were remarkably empty three months ago, from soft export demand, a good lead indicator.

All of that was hidden by strong services demand, and in closed economies (as the UK is oddly becoming) there is no relief valve, and hence it suffers embedded high inflation. But clearly consumption is dropping in the US, recent retailer numbers are all over the place, confirming those China export stats.

While on commodities, the failure of sanctions to impact energy is ever more clear, and I doubt OPEC’s ability to stem the energy glut. As a final blow to value stocks, “higher for longer”, on interest rates, which we have been predicting for two years, hurts indebted companies, who increasingly have to refinance at high rates. It also makes their dividend yields less attractive.

When rate cuts do come, growth having survived the storm, may well soar; as we have noted before, the prevailing fashion in investing heavily favours so called “tech moats” and dislikes debt. That markets keep seeking out new moats, real or imagined, is all part of that.

The speed at which digital currency and virtual reality have become old jokes, but generative AI will save us all, is remarkable.

Bond Dilemmas

In bonds we have seen no point in our lending to governments at rates that are below inflation; in most of the world as inflation falls, bonds still remain unattractive, as yields then start to drop too. So, the bond trade has been messy to say the least.

With greater certainty about a consumption recession, the fear of defaults also rises, and the longer rates are high, the more that refinance risk looms. Jumping a spike is possible, vaulting a table, without spilling your drinks, rather less so.

There is also still a ton of money parked up in fixed interest, just waiting for the equity ‘all clear’.

Lost London?

The UK market (yet again) simply flattered to deceive; I struggle to see much hope for it. While we can hope the likely change of government will be an enhancement, it really will just entrench welfare dependency and producer capture of state services, albeit in a rather more disciplined way.

The risk of Brexit always was that we would use our new freedom to rebuild old prisons. Can a new flag on an old workhouse change much? As for where our stunningly high inflation comes from, again, it must be our own creation, the Ukraine energy peak is now a dip, so it is not imported.

While no one wants to say it, tax rises, especially of such magnitude of corporation tax, in particular, are inflationary, but so is the cheap theft of frozen income tax thresholds. Trade unions employ good economists too, they negotiate for higher take home pay. Rate rises also cause extra inflation, especially with our persistent high national and consumer debt levels.

Sterling strength (it is now moving up against the Euro too) is a sign of markets seeing the UK as the best bet for avoiding rate cuts (and for getting more rate rises). That is not a good sign domestically.