Sea change

A trio of influential knaves to worry about this week, united by a belief that “this time is different”. Well pantomime season is behind us, however we can still all shout “oh no it isn’t”.

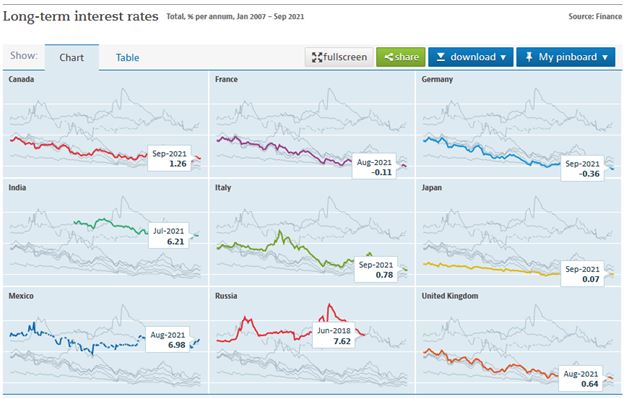

Boris seems to be the least of our problems, if the greatest of villains, for the scurrilous crime of enjoying himself, what a rat. While Powell is providing an increasing threat to the poor and exploited across the globe by generating financial instability, and the lamest of the lot, Lagarde is just repeating a political line. The Euro zone debt figures look like this. A sharp rise from an already overstretched position, but still benefiting from falling rates, so when that rate line turns, the problem will really bite.

Will markets ever trust the Fed (if they did this time, outside the gilded denizens of Wall Street) again? Hopefully not, the trouble with putting administrators in charge of Central Banks is they rely only on historic facts, it is in the job description, that’s what they polish, hone and serve up.

But the economy is dynamic

The mismatch is that the economy is dynamic, and has no printed rule book, beyond that of the rocket; what goes up, must come down, immutable like gravity. And you simply can’t wish gravity away.

So, this Fed is programmed to repeat what it can see looking backwards, and all the obedient commentators on Wall Street who simply echo its nonsense, are of little use, except to fleece the gullible and to signal false comfort to one another.

Having said for most of last year “there is no inflation” they have turned on a sixpence, to say inflation is now out of control. Talking of six or seven rate hikes; they wish, just banker’s fantasies. Although markets, not surprisingly, are now suddenly jittery.

Investment implications

This week we went from feeling over 20% cash was too cautious, to feeling we had missed the boat on value stocks, back to feeling 20% cash was really just fine, all in the space of four short days.

So, because that sea change in inflation expectations was so abrupt, this is a genuine dislocation, we do see the NASDAQ and both the concept stocks on infinite multiples and the mega tech stocks on thirty- or forty-times earnings, as in some trouble, in a process that does not feel over yet.

There is a ton of selling, and the spoofing assets, including crypto, will be heading down, in a dip that feels likely to be around for a little while. But two things stand out, firstly until rates start to top out, this excess money simply can’t go into bonds, so what happens to it? Secondly if the market assumptions about Powell and Lagarde are both right, you are going to be paid handsomely to hold dollars, while simultaneously being charged to hold Euros. We don’t see that as sustainable either. One must be wrong.

Looking ahead

This is why Lagarde’s confidence in no rate hikes, feels like a lawyer’s bluff, as if currencies move, it won’t be her choice for long. While uninvested money, on which fund management fees are still charged, always makes asset gatherers nervous; it will all go somewhere.

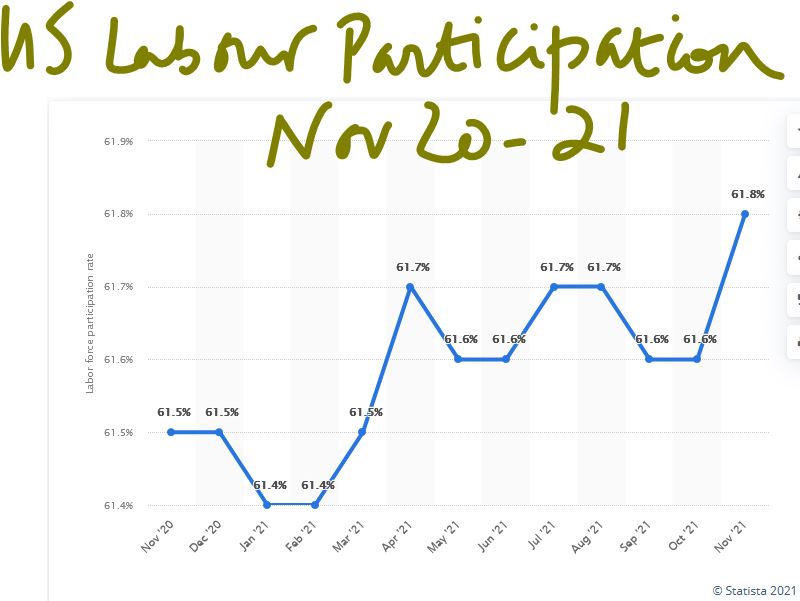

That also leaves the question of how much growth we will actually see, as if it is below expectations, then inflation will be choked off, labour force participation will fall, US rate rises will run out of steam. There are already signs of that. While given the scale of market movements, the ending of bond buying by the Fed (long overdue) and even a modest run off of the balance sheet, will be pretty irrelevant, both are really drops in the financial ocean.

The froth blown off

So, the good news is we will see normal investment conditions, the froth blown off, bonds producing a yield, along with slower growth and moderating inflation, which we do feel will be backing off by mid-year. All of course will rather depend on the progress of COVID, because we still see (and have done for nigh on two years) this inflation is directly caused by COVID responses.

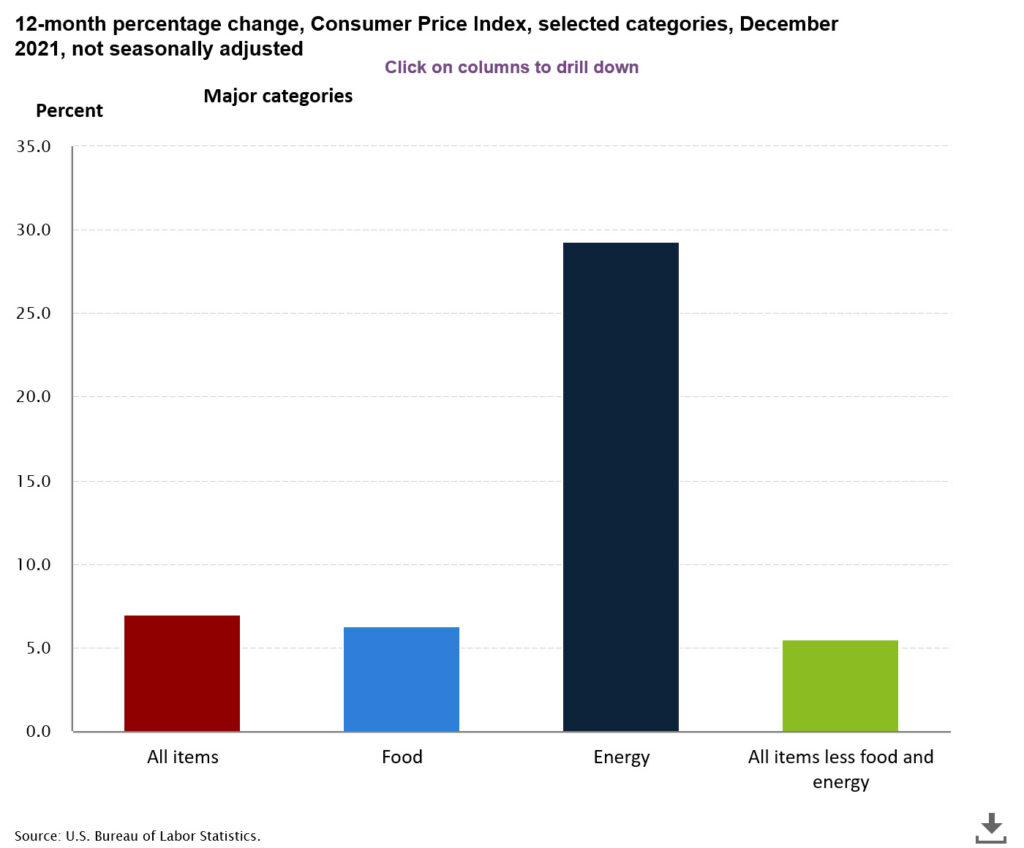

Reducing the output capacity of the economy, with no cut in demand, has to cause price rises. These price rises will exist everywhere COVID does, so trying to pin them to a single cause or location is not easy. They will persist until the demand/capacity equations correct, which with COVID is a multi-year task.

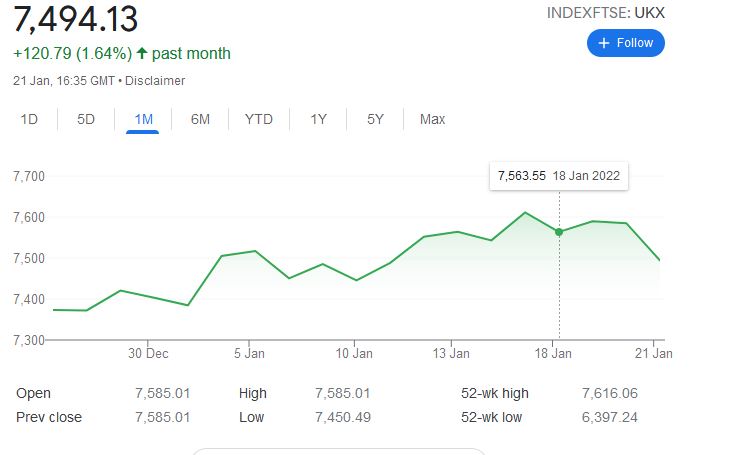

The FTSE finally gets a look in

So, a sea change yes, a market dislocation yes, but if it is as bad as is currently feared, with some big winners resulting in the financials, real assets and energy. All of which, on those fundamentals, still look to us good value, hence the visible support for the FTSE 100.

While if it is not that bad, sufficient money will flow into US Treasury stock, from low interest areas, forcing the dollar to rise, and rates down, until other areas are simply pulled along. So no, we won’t then be getting seven rises on this data and equity markets can start to relax.

And what of Boris?

Finally, Boris, now degenerating into farce, but much as we hate what he has become, we recognize one wing of the Tory party feels he is too right wing, while another feels he is too left wing. Both dream of replacing him with their own, but in so far as he splits the difference, the risk that the other faction wins, should keep him in office.

Either faction will demand more of his replacement than they can ever deliver, given that core fundamental split, so such a divide simply hands Downing Street to Keir Starmer. For now, I still feel he survives, and given his nature he will remain impervious to change, but remarkably adept at promising it.

Sterling seems notably unfazed by it all.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Limited

THERE IS NO SANITY CLAUSE

Three big topics this week from three central banks, all of whom look to be in a muddle, with their knitting all jumbled up and highly implausible. Entirely predictable inflation meanwhile threatens to sweep them off their path, as they tinker with micro adjustments to interest rates.

Boris is diverting, but we doubt if it all matters; pre-Christmas entertainment. If he were logical or even vaguely numerate, he would change, but he’s not, and he won’t, but nor does he need to.

The Lib Dems win a by-election, that Labour fails to contest, but it makes no difference in Parliament, and it lets Boris look contrite mid-term. He will survive this with ease.

Which is not to say he should, or that he’s not making a hash of COVID, the sequel. In keeping the NHS in its current format, Boris fails to ask, as many have before him, whether it is still fit for purpose. This remains an urgent question. It can’t simply collapse every year.

Bailey - Bank Governor and historian

But perhaps Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, understands the extraordinary risks Boris poses to the economy, and has hiked rates to show that. A Cambridge (Queens) historian, with a doctorate on the impact of the Napoleonic Wars on the cotton industry of Lancashire, he will know full well the impact of a French orchestrated trade war backed up by a dodgy pan European monetary system.

A consummate insider, via the LSE, he moved on to the ascending ladder of the Bank, which did include a slightly unfortunate move into the FCA. This turned out to have rather more real villains than he was used to. Married to the head of the Department of Government at the LSE, he will be very well aware of the political game and the current mood in Whitehall.

He’s seen enough inflation and has decided the Bank must pretend to act. Not only is the rate rise trivial, but it also coincides with a continuation of Government bond buying (QE), an odd call. That the last thing the economy needed was still more liquidity, has surely been obvious for eighteen months now.

Christine Lagarde and Jerome Powell

In Europe the same mishmash exists. We have been hearing Christine Lagarde explain why the ECB is now accelerating one asset buy back (APP) while ending another one (PEPP). She was winging it with the phrase “utterly clear” in answer to a pertinent question, when it was clearly anything but. Still, she did seem to have her ear rather closer to the ground on wage inflation, at least compared to Jerome Powell.

He by contrast has been caught with his pants on fire, trying to weasel his way out of the Fed failing to spot inflation, by saying that most market commentators agreed. Remind me, which is the canine, and which the wagging appendage?

Basic economics - why inflation arises

We called it on inflation as soon as that stock market rally took off, and for the simplest of economic reasons: the pandemic had reduced global productive capacity, so absent a change in price levels, the economy was less productive, profits were therefore lower, competition would therefore be less (unless prices rose), and total production must fall. Less output, same demand will always mean inflation.

Forget the energy issue, forget supply chains, less capacity, more demand always means trouble. True based on that one schoolboy error, the dopey measures to reduce capacity further by more regulation, hiking the minimum wage, paying people not to work and so on, plus embarking on accelerated decarbonization and a few new trade wars, was not going to help much either. But please no more “surprise” inflation, it was baked in. (See extract from my book, Smoke on the Water, blog dated July 2020, title re-appearing shortly on Amazon)

After the interest rate rise

However, we have also long felt that interest rates can’t rise enough to stop inflation, but that as governments have to back off fiscal stimulus, as they are already overborrowed, the lower productive capacity will itself shrink demand, and in the end cause inflation to fall. But we see that as taking years, not months.

Why are interest rates not rising to combat inflation? No political will for a start, and any one country that gets too far out of line will find currency appreciation itself addresses the problem. So, do we believe the US “dot plot” suggesting three rate rises in 2022, while the Euro zone does nothing? We struggle to.

Powell is still clinging to the lower workforce participation rate (which matters) as a signal to defer rate rises and not the unemployment rate (which is more closely related to vacancies) and hence of less fundamental relevance. While employment is great, it will still be unattractive if inflation (and fiscal drag) takes off, thereby holding the participation rate low.

This does still suggest dollar strength, while sterling like other smaller currencies always needs to be wary of getting too far out of line with US rates. But also, a need to fathom out the new look economy. To us, it does not seem service industries that rely on cheap labour are operating in the same world they grew up in. Certainly not if it is onshore.

There is a forced change in government consumption patterns (and hence employment), and this will also be telling. We are heading into quite a different market, when all this shakes down.

Sitting on high cash levels over Christmas, as we are, is pretty cowardly, but if you can’t see the way ahead, slow speeds are usually safer.

We do also rather agree with Chico Marx, this year at least.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

Which is the Leviathan?

This is a week to ponder the role of private equity in portfolios, in what may be an early phase of a great investment and technological explosion. There seems to be no sign of higher interest rates and a stubborn refusal by Central Banks to care much about inflation. The talk of a UK raise always looked to us like a head fake which we ignored.

Spotting good and bad private equity

So first to private equity, a beast that comes in many guises, not all benign from an investor viewpoint. All liquidity fueled equity explosions come with a heavy loading of chancers; Bonnie and Clyde’s rationale for bank robbery remains valid.

Good private equity relies on management being superior to that of their targets. This can be in their analysis, their execution, their swiftness of foot or their innovation. All of this generally flourishes away from the hidebound inertia of many listed companies and their professional Boards of tame box tickers.

Bad private equity uses accounting tricks, the malleable fiction that the last price is the right price in particular, and the terrible phrase “discounted revenue multiple” which is a nice conceit for “never made a profit”. All of these share the same vice of management marking their own work.

So, we struggle with the likes of Scottish Mortgage and its little array of unquoted Chinese firms, the alphabet soup of non-voting share classes and love affair with management. Maybe they are that skilled, but nothing that looks like a real two-way market is evident to us, in many of these valuations. We have by contrast long admired Melrose Industries for their quite ruthless devotion to turning over their investments, good or bad and stapling executive pay to actual cash realizations paid to investors.

Where we stand – given our strategy

For an Absolute Return specialist there are added constraints: we want to hold under twenty positions altogether and all in ones we can sell tomorrow afternoon. And we like holdings where valuations are transparent, there is no gearing (there is usually quite enough in the private equity deals already), and you can pick them up for a fat double digit discount: oh, and we do like a yield too.

So, we are looking for big, listed options with hundreds of high-quality funds bundled together and for any yield, a bias towards management buy outs. We are certainly not at the venture capital end, with silly pricing, high fail rates, unrealistic managers, and not a decent accountant in sight and aspirations to change the world. Met those, invested in too many, and donated more shirts off my back than I care to enumerate to their serial failures and inexhaustible funding rounds.

But there are good things about Private Equity, one is that in a rising market, it can be like clipping a coupon. The accounting rules require them to be backward looking, so coming out of a trough they are typically reporting on valuations that are three or four months old, which in turn reflects business activity up to six months old. As they trade at a discount of typically 25% or so, you can buy today at a 25% discount to the value of the business they were doing in the spring. There are no guarantees, but for most, that was a lot worse than current conditions, so today’s price is simply wrong. This is a time machine that lets you buy now but pay at old prices.

Watch for built in volatility in private equity

These lags are complex, the reference points are often public market valuations, and so there is volatility built into them. While in an Absolute Return fund, not only are choices limited but the overall exposure must be too. However, in those rare purple patches of fast recovery and expansion they are excellent for performance.

What kills these bonanzas off is tight credit. In part they need debt for trade, but also their realizations rely heavily on it. A closed IPO market does them no good (just as they enjoy an exuberant one). That is a risk, as liquidity starts to tighten, that this will hurt, but as Powell and the Bank of England both showed, there is no political appetite for that just yet.

The UK and US on taming the leviathan

Indeed, Sunak’s UK budget yet again feels reckless, devoid of any discipline and with every department cashing in. Government spending is predicted to rise to 42% of GDP by 2026, a fifty year high. Healthcare alone is predicted to have grown by 40% in real terms since 2009 (both estimates from the oddly named Office for Budget Responsibility). At that level of loading, it is inching closer to hollowing out the entire budget and causing it to implode. (Leviathan was just such a creature “because by his bigness he seemes not one single creature, but a coupling of divers together; or because his scales are closed, or straitly compacted together” feels an apt description of this new giant state apparatus.)

But that gamble means there is no room to pay higher interest rates, or the economy will be reduced to a double-sided monster. The one face devoted to raising debt and levying taxes and paying interest, the other to feeding out of control public spending, with nothing left in between.

Thanks in a slightly odd way to a Democrat Senator, America has avoided throwing itself under that same bus, but with no effective political opposition the UK is now powerless to resist. Sterling’s relentless decline from the summer high and a FTSE 100 index still below its pre-COVID peak signify what markets feel about all this.

From the London Stock Exchange graph

So, while we were more bearish than we have been all year, in terms of asset allocation, at the end of October, we have yet to call time on the Private Equity cycle, that has provided such a powerful boost this year. It still feels good value to us.

Of course, we recognize too, that the populist fear is of the wealth creators and an opposing adoration for wealth consumption. Unlike politicians, however, we are tasked with producing real results not vapid dreams.

I guess we can each choose which to regard as the leviathan – the burgeoning state, or private equity.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

Caution: Bumpy Road ahead

Puzzle: World markets have whipsawed in the last few weeks, from high anxiety to an almost beatific calm. The VIX volatility index has dropped to pretty well a post-pandemic low. Which should mean we all agree, but on what exactly? Rising inflation, yes, but how durable, and caused by what?

And that, we all accept, will make interest rates rise, yes, but how high for how long? Markets we feel are, to say the least, fragile.

At the turn, we know that moves can be dramatic both ways, for markets.

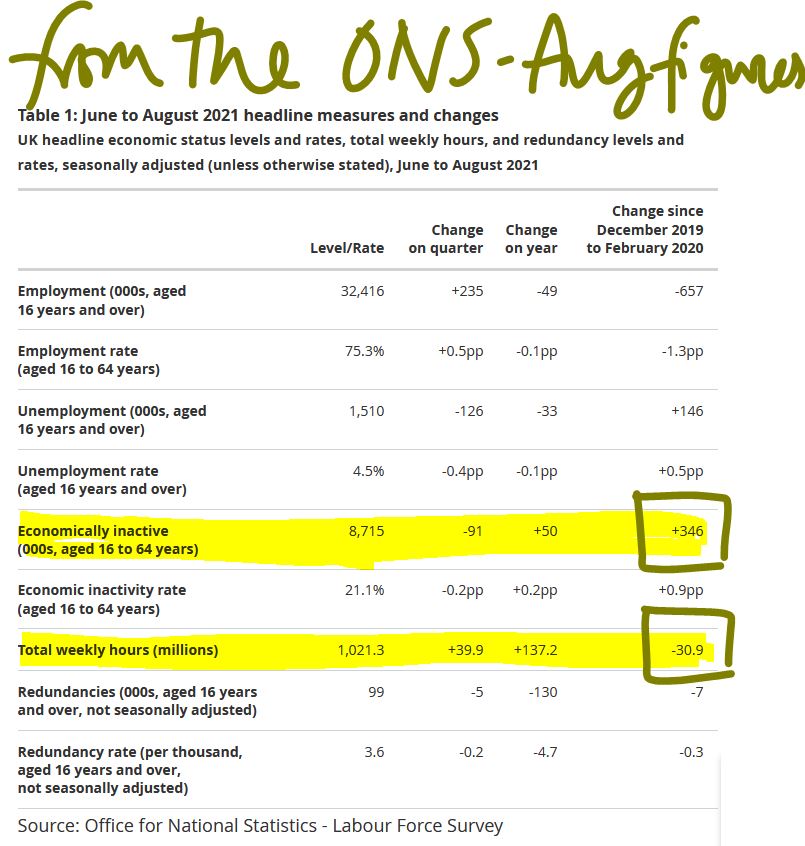

Are we really seeing a labour shortage? The UK truck drivers’ situation

What we see now is not a labour shortage, and hence political talk of stemming migration and higher wages is well off target. What it is, in part at least, is a failure of the routine operations of an incompetent government, something politicians typically don’t want to discuss.

The government has insinuated itself into so many areas, with its complex regulations, that the market economy now lies ensnared in myriad interlocking regulations, backed up by a deeply entrenched blame culture (and its friend the compensation economy).

To take one example, there is no shortage of truck drivers, but there is a shortage of qualified, approved, signed off and regulated truck drivers, because as part of the destructive lockdown, the government just halted the conveyor belt of required testing and approvals.

Truckers’ wages have for long been too low, of course, especially for the owner drivers in the spot market. What we have is not a labour shortage, it’s a paperwork shortage. The difference is vital for how enduring inflation is. A new driver will take a couple of decades to grow, but clearing a paperwork jam, a few months. One is enduring, the other transient.

Withdrawal of older workers from the labour market

Work after all is something of a habit: once it is lost, it can be hard to understand why it existed. So, we see a marked increase in older workers in the UK who have just withdrawn from the market (Some thirty million fewer hours worked - see figure below). That too is not a labour shortage as such, they all still exist.

But if work was of marginal benefit to the worker, and the costs to resume work (actual or psychological) are high, disruption will cause the fringe or marginal job to be unfilled. Yet again more in the transient column than permanent.

Someone will waive the rules, or the government will notice, well before all drivers get paid high enough wages to cause embedded inflation. In any event articulated fuel tanker drivers tend to work for big employers, with good conditions, and are well organized. They have to be, after all they drive mobile bombs. The spot operator on a rigid rig is in a different market.

Inflation will most likely be transient

So, if it is not an actual labour shortage, it won’t cause wage inflation, and will be transient. Some other areas reliant on highly skilled older workers will continue to see standards fall, but generally younger workers will over time fill those slots and gradually acquire those skills. And it won’t be a long time.

Our view from way back was of 5% plus inflation and labour markets that struggle to clear this year. We were wrong to not foresee the failure of regulatory processes to keep up. However we still do see a permanently higher post COVID cost base and therefore in certain sectors, a large amount of marginal productive capacity are likely to be withdrawn from the market.

With a banking system that still struggles to offer commercial finance to the SME sector, because of excessive regulatory caution, there are swathes of jobs that have simply gone. So that labour will in time be redeployed. The current concern is that many of these workers show no desire, or ability under current conditions, to return to the market. But when they do, the capacity that has been destroyed will slowly return, and once more drive down prices.

Nor should we forget just how much the Exchequer loves inflation, as fiscal drag, their beloved tax on higher prices, smooths away so many budgetary blemishes. They will let it go, if they possibly can.

Commodity prices

On the input side we do still see commodity price rises as transitory, at least within the energy market. As others have noted much of that too is regulatory failure on a grand scale, not a true shortage. Price fixing by the state is a notoriously foolish concept, as we learnt in the 1970’s.

There are a number of other supply factors at play too, but while some will recur, most are temporary.

How long do we think the inflation spike will last?

So yes, inflation will spike, and yes it will stay elevated for much of next year, but no, we don’t see it as necessarily durable, once COVID restrictions and related behavioural changes vanish.

We are still pretty certain that the political costs of aggressive interest rate rises will outweigh any perceived price control benefit. As long as some Central Banks hold off rises, it will be very hard for others to do so, without sharp currency moves or bringing in formal exchange controls. That would in turn spook markets far more than rate rises.

The next phase of markets

All of this says to us that a major market dislocation, despite the benign signals, lies ahead in the next six months.

Markets shifting rapidly are more a sign of uncertainty than of a new degree of confidence, and we simply don’t trust it. We see inflation as apparently out of control, but no significant interest rate rise response is feasible. That can feel like stock nirvana, but also like investor purgatory, as you have no idea what is or is not a sustainable profit.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

Thin ice skaters or savants?

Are we drifting out further from the shore of reason, confident we can slide gracefully back to safety, or do we have insight others lack? Perhaps rates just can’t rise, whatever the inflation rate? If so, they are a paper tiger. While in a week others have pondered the failure of UK investing during this century, we look at why our biggest bank seems to hate the country.

I’m talking about the economics prognostications from HSBC, our largest bank. Following an intellectually flawed change in accounting standards (yes, another one), on top of the insanity of “mark to market” comes the “predicted loan loss model”.

Now professional bankers (unlike those in fintech) don’t make loans to lose money.

So, the politicians have instead required them to assume that they do.

Do the regulators know the industry they’re regulating?

Imagine portfolio management where you assume a certain portion of your buys always fail. Might be true, but how? And if you admit you have to buy a certain number of your holdings to instantly lose money, what do your investors feel?

But although banks advance money on the basis of their credit committee assessments, the hordes of regulators deem some of it is immediately lost. Being rational people on the whole, the banks, not great fans of predicting the future (given their record), hire economists to do this for them.

Economists, as we know, actually know little, but they do build nice econometric models. The regulators, who know even less, tweak the models, the bank Boards (see above) also tweak them. Soon every model is so tweaked that the economists wonder why they bothered.

UK shown as the riskiest of places to lend

Which leads us to page 62 of the HSBC Interim Report. We read it, so you don’t have to. There on the excitingly named, but dull as ditch water section called “Risk” it is set out.

Now HSBC lends globally: Mexico, India, Vietnam, Peoples Republic of China. So, guess where “The highest degree of uncertainty in expected credit loss estimates” relates to? Apparently, the basket case to end all wicker weaving is . . . Yes, the UK.

How?

Well first up their ‘central scenario’ model sees the short-term average UK interest rates for the next five years, as 0.6%. Which at least is positive (unlike France, as they hate Macron even more), France (i.e., the Euro) rates are assumed to stay negative till after 2026.

This gloomy central scenario has a 50% chance, although for France it is a tiny bit better at 45%.

Now these are central estimates, but their “downside scenario worst case outcome” for the UK is heavily weighted, with a chunky 30% chance, and oops, France then gets a 35% chance of that disaster, neatly using up the slack just given to them, by the central scenario.

Oh, and there’s worse: house prices crater, double figure unemployment is locked in etc.

And that’s a combined 80% of outcomes sorted; for a bank, that is pretty near certain.

China compared to the UK and France

What about Mainland China, then, their biggest market, if you now include Hong Kong. Well like the US (75%), China is at a high (80%) central scenario certainty, with Hong Kong at 75%. The worst-case scenario for the PRC is ranked at just a measly 8%, the lowest of any of their major markets.

Call it impossible - a prediction that China can’t fail.

Well, if that’s what the economists believe, who are the dumb Board to argue? Well of course they can, to cover their well-appointed posteriors, they then chuck another couple of billion of extra reserves in on top of the doomsday forecasts.

So, you see the vortex, everyone, regulators, economists, non-executives are just adding to reserves, like the good old days.

Maybe they are right, but we are seeing very little sign of those incredibly low global interest rates for five years, negative in France, 0.6% in the UK, 1.1% in the US? Really? If they are right, the markets are wrong.

And it is not just technical, with a 35% chance of France hitting the worst-case scenario, no wonder the Board has shipped out their French operations to a fin tech start up, albeit one backed by private equity giants Cerberus. Not an outfit known for overpaying. With five-year rates at 1.1% the dash for cash in the US makes sense too, selling out of their retail side as well. While with a virtually nailed on, global leading, 5% five-year average GDP growth in the PRC included, surely time to expand there?

Their loan book does not bear out HSBC’s bullish estimates of Chinese infallibility

So it is with some trepidation that we look at their loan book, on Real Estate, in China. It must be massive? Certainly, markets apparently assumed so last week. But no, a paltry $6.336 billion, for HSBC that’s a rounding error. Luckily too, all rock solid, just $28m of reserves needed, although given their certainty that almost feels excessive. The Board probably slipped that bit in.

I have great admiration for HSBC, and for me personally it is a long-term hold, but I have much less regard for regulators and ‘economists’ models, about which only one thing is certain. They are wrong.

So, I try to just strip out the predicted loan loss nonsense, but it is still driving asset allocations, even when palpably false. It explains much of the last two year’s volatility in bank share prices and reported profits, it also justified the highly damaging dividend ban.

Yet the HSBC share price is still not much above 50% of its pre-COVID peak. Great investor protection that was, it hammered HMRC receipts too, for what? Based on what?

Does anyone challenge those weird scenarios internally at HSBC?

Is there really a 35% chance of France virtually collapsing in the next five years?

Or is this just part of cozying up to China? In which case as the IMF has shown, bankers accused of fiddling data for China, are not always seen as professionals and can lack credibility.

Regulators should not impose those odd fictions on real investment decisions either.

If they do real economies and yes jobs, suffer.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd