A long view this time : Has the price of capital changed for good? How bad is the UK position? Oh, and the unusual universality of colonialism.

A Far Off Galaxy

Let’s start with colonialism. I have been reading about the benighted past of Bulgaria (R.J. Crampton, 2nd Ed, CUP). A Bulgarian I know said that the country ‘has a knack for picking the wrong side’ – a little harsh, I thought. However, it has always existed as a colony, aside from a brief imperial phase around the last millennium but one, and before that when it equated to Thrace, almost as far back again.

Given the option, Bulgaria recently opted to join the Western European empires’ current formulation as the EU and NATO – the latter being the armed wing of Western thought. Bulgaria had suffered horribly under the Soviets, with a steady and ruthless coercion of an existing multiparty democracy, at a speed just enough to keep outsiders ignorant, or if not, passive.

That history gives me a whole new viewpoint, on the string of broadly similar states. The Balkans and The Middle East all appear in a new light, and indeed I start to comprehend the bitter sideshows (as they seem now) in both World Wars, over that same terrain.

The collapsing empires (Russian, Ottoman, Roman,) seem more influential than the current rulers in so many former colonial states. They are really not, as we think now, a series of nations fighting for ‘independence’. In most cases that independence is fragile to the point of being mythical, while the internal fissures are enduring. The cracks of nations within empires, not of states within a world.

Now You See It

One passage in Crampton’s work stood out “by mid-summer social and industrial unrest were widespread with strikes by civil servants. On transport networks, and despite the provisions of the law, in the ports and medical services. The government was forced to grant a 26% wage increase to all state employees, an action which weakened its attempts to control the budget deficit and inflation and which did little to impress the international financial organisations.”

Written about conditions just before another wrenching Balkan realignment last century, this rather made me stop and reflect.

A parallel with the UK?

Just how close are we in the UK to that edge? Lost in a warm feeling for individual strikers and their causes, and a very British willingness just to plough on, there still seems to be a real danger.

I am well aware of our great national strengths, in the arts, our language, higher education, science, heritage, even logistics and retailing – they are enduring causes for optimism. But long-term investors need to weigh up the recent damage, especially the loss of political capital by the “responsible” right, the high levels of debt and taxation, which coupled with low productivity, could also spell trouble, the certainty of ongoing nationalism and the unhealed rift of Brexit.

There is danger too in the probability of a Labour government, which however centrist the leader is, will have left wing factions to assuage. It is equally dangerous to continue our recent experience of minimal ministerial experience. I hope the change won’t be as bad as I fear, but it will probably be worse than I hope.

This remains a reason for the FTSE to be anchored to late 20th Century levels, despite almost every stock I research looking cheap. The fear of being still cheaper tomorrow rules.

Do Markets Care?

On the other hand, re-pricing capitalism after the decade of populist nonsense by central bankers does feel pretty good. If you have no cost of money and no reward for savers, financial gambling prevails.

All of this raises a key issue: is the apparent resurgence of speculation (the greater fool theory of investing) permanent? In which case investors should probably just watch momentum. Or is this most recent re-run of the last decade’s speculative phase, really transient?

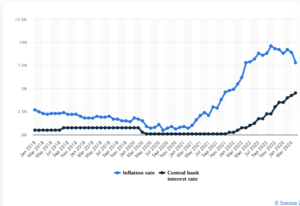

For a better view, see this page on Statista

As long as inflation exceeds the cost of money, assets will likely rise; the widespread return of real interest rates (a point we are almost at) should slow that down.

After that point what matters is cash flow, and whereas gambling will favour growth stocks, real returns come about when interest rates are high, but inflation is also falling. The gap matters and we are not there yet.

This is probably the crux of the next two years, and we doubt that having had a serene and slow drift towards recession, there is any reason either to expect a suddenly faster descent now, or really to expect the corollary, a sudden fall in interest rates, to offset a deep recession.

If rates stay high, but have indeed peaked and inflation declines, value investors should be in a better place. If they get it wrong, they are at least paid to wait.

As we have seen in the last twelve months, growth investors fuelled by borrowed money really do need a rising market, they get hit twice if it falls: both through a loss of capital and then the need to fund loss-making assets at real rates.

The Monogram View

Overall, our position has been that fundamentals should win, but we suspect momentum will win. Spotting the next momentum shift early, therefore remains a powerful driver of returns.

One narrative of 2023 (so far) is that the SVB crisis and stronger growth combined led to far more liquidity than markets expected. This fed into the gambling stocks, giving them momentum.

So, although the first half was not what we expected, the second half might still be. But it is just one narrative, and it may still be the wrong one.

Note : Further reading, for those interested in Bulgaria :

See also, The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Obolensky, Dmitri.