The Glass Bead Game

We look today at a domestic version of a complex, rulebound meaningless pursuit that too many of our brightest and best waste their lives pursuing, and whose twists and spirals ultimately signify nothing. I mean the UK Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), of which I took a tour this week. Almost nothing there is as it seems.

Meanwhile markets reprise 2023, with tech or bust once more. Although tech and bust is the market fear, as fiscal stimulus and services inflation hold rates too high for some to survive.

UK OBR

The OBR was an explicitly political creation of the coalition government in 2010, with a remit to somehow restrain the ever-increasing debt governments take on, to bribe electors. They were also keeping half an eye on the much older ‘debt ceiling’ style US legislation. It failed; so now the OBR just thrives on telling the government how much more it can spend or not collect, with spurious accuracy; purportedly managing public money.

It doesn’t forecast anything as a forecast is an expected outturn. All it does is crank the handle on the old, discredited Treasury model, creating projections. A projection is 1) a ‘what if’ assuming all other things are equal and 2) only as good as its underlying model.

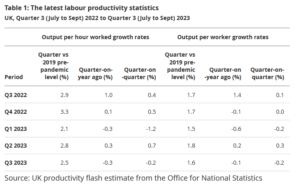

One clear flaw is the requirement to take government spending plans as viable when they are usually not. They also have no idea where public sector productivity is heading. It has no remit to look at how productivity might be helped and no capacity to look back at how wrong its old ‘forecasts’ were. That is the job of the National Audit Office, it seems.

It also won’t talk to the Bank of England, as that organization has executive powers (to raise or lower rates) and the OBR apparently must just be a commentator: more glass bead rules.

So, it fiddles with the model and its six hundred inputs and countless equations to give precise answers to pointless questions, because each answer sits in its own vacuum.

There’s a heavy focus too on tax revenue, but with quite a thin staff, this results in excessive reliance on HMRC, who can be hopelessly wrong (and typically over optimistic on tax yields). But again, if the tax bods claim some complex, job destroying, arcane nonsense will raise income, in it goes. The side effects of such decisions must also be ignored.

It has no remit to assess how taxes impact productivity, which partly explains many of Hunt’s blatantly anti-growth measures. As a result, the economy is locked into low productivity, getting steadily worse.

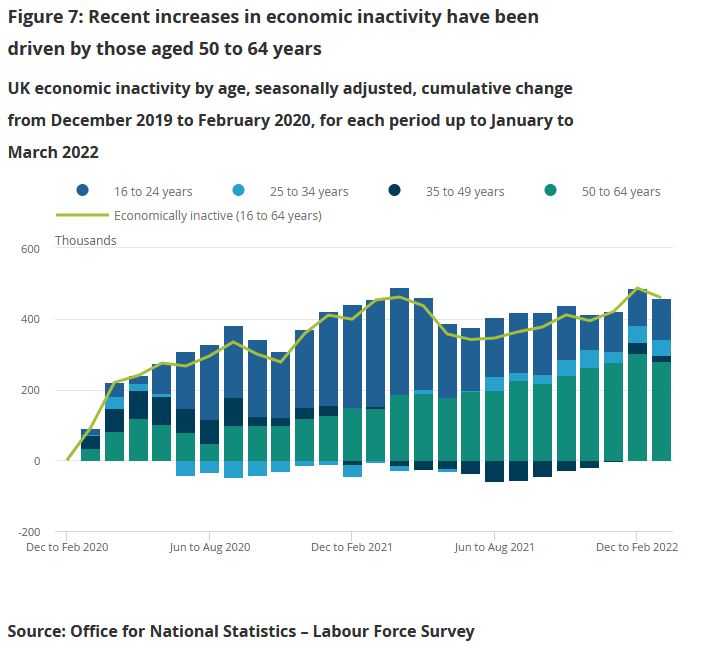

From the ONS flash report here

For all that the financial press will be full of the OBR cogitations on the forthcoming budget (March 6th). One little bit of power they do have involves a requirement for the Chancellor to give ten days’ notice of the budget contents (hence no doubt the usual leakage levels) and for two months before that, they sift through proposals and indicate how each, in isolation, would work. The economy is an interconnected entity, they know, yet there is no attempt to give us an overall view.

THE LOST RALLY

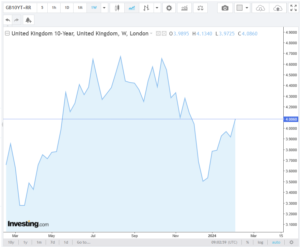

I have few rational reasons why anyone would lend the UK Government at under 4% for ten years, were it not for some foolish faith in the OBR projections, without reading the small print.

Which brings us to markets: back in November the UK ten-year gilt yielded 4.5%, by about Christmas falling to 3.5%, and now it is back over 4% and headed higher.

Chart from this website

Quite a spin in ten weeks for a ten-year duration instrument. This is why that Christmas rally in value stocks was ignited, and indeed started to push out into Real Estate, various Alternatives and certain smaller stocks.

Although it didn’t move those stocks most sensitive to the credit markets, who will need to rollover/refinance current debt. This affects for example, the renewables, private equity, and office property. The problem there is of both rates and availability. With the scale of asset mark downs, whether interest is 6% or 8% is not the issue; there is no funding appetite even at 20%.

The year-end rally moved a wide group of stocks, from extremely cheap to still very cheap. We then realized that it was not yet safe to go back in, so buyers evaporated, and prices faded. With state debt at 4%, against persistent inflation, fixed income is also oddly unenticing. So, the market default has been to pile back into the biggest, most liquid, US tech stocks and similar easy-in/easy-out momentum trades, like bitcoin.

There is little sign of deflation in services, no evidence of it in housing, where supply issues dominate, and little in financial services; indeed, all the supply side mess of COVID and excess regulation, is simply getting worse. Public sector pay inflation is also high and going higher (don’t tell the OBR).

This does not dent the 2024 story of cutting rates and hence higher stock markets, but it may require some patience, and that delay may itself create more pain.

The Glass Bead Game and the ‘lost marbles’ qualification for office

Our games of self deception are not to be confused with lost marbles of course; it turns out that the onset of senility is now a bar to being prosecuted for storing secret state papers and also, somehow, a recommendation for re-election for four more years, to the most powerful post in the world.

If that ends up giving us Trump again, by default, presumably he will at least have a defense in future years, against those same crimes? He does not have the “Biden defense” available at present, perhaps thankfully.

As the OBR shows, very clever institutions can come up with very silly solutions.

WENN DU LANGE IN EINEN ABGRUND BLICKST

We look briefly at China, not as an investment, but more an existential threat. And we finish the lessons of the Greek coup in 2015. While little else surprises? Except perhaps the pessimism apparently shown by the long bond.

But even that might have a good reason.

DIRE STRAITS

I looked idly at a certain pink paper’s New Year quiz and asked my companion for views, and on most topics, we had one, or could find one. But on one, ‘will Xi invade Taiwan?’ I had no idea.

Not because after Ukraine there is any doubt it would be mindlessly stupid to do so, and plunge China back into the dark ages. That much is obvious. There is no way China can “go it alone” - without Western markets, capital, and innovation, it heads back to where Iran, Pakistan, Congo, and Argentina have been.

But a distant echo tells me that I don’t know for certain. Perhaps my confidence that Putin would not be so stupid as to invade Ukraine, tints my view; I was wrong there.

I am also largely assuming any military contest is unpredictable, so I tend to focus on the long-term economic impacts alone. But I still don’t know that Xi won’t try, which will clearly crash world markets.

I will deliberately not gaze into that abyss, but I can’t ignore it. The best response I have is where two stocks are equally attractive, and on like valuations, I would buy the one with the lower Chinese exposure. Maybe my limited action says that I think it is possible, but really not that likely. The other option of course is adding to gold and safe haven currencies.

Looked at a Swiss Franc graph of late?

From : Google Finance currency page

Most investable firms can shed China, just as many have shed Russia, but at a much higher price. The reciprocal asset seizures will be vast.

And although it won’t cripple Starbucks, Tesla or Apple, it will be a big slice of asset destruction for them.

NO DEMOCRACY

Back to Greece - when we last wrote it was to note the ravages imposed by the EU and IMF on the Greek economy, and how the scars still remain. But completing Yanis Varoufakis and his seminal tome, other contexts are clear.

As an academic his note taking and indeed voice and video recordings were quite an exceptional contemporaneous record. Not just of Greece, but of how Europe really worked, in a crisis.

We forget now, that Ukraine also needed a big bailout in 2015, and a choice was made as to which mattered more to, in effect, Germany. The answer in 2015 was Ukraine, with the late Wolfgang Schauble wanting Greece out of the Euro, and Angela Merkel seeing that as a lesser evil, for Germany, than the collapse of the Ukrainian economy.

There is very little ‘EU’ in this incidentally, Germany was the dominant and controlling creditor. The IMF largely sat safely behind its super creditor status. As Yanis notes the IMF funds itself on interest, and that mainly comes from having plenty of distressed debt. Not an attractive feedback loop, however logical. And of course, it largely stood back from Greece – inactivity is often an action taken.

Moving on, the Greek crisis was closely followed by Brexit, at the time we thought that was chance. It is clear it was not, and both sides had learnt a lot from the prior event, to take into the next battle. The EU and Merkel in particular had no interest in rational arguments, having waded through all that guff in Greece; you can see Cameron may have been useless, but he really had no hand to play in his “re-negotiation”. Simply ‘nein’ had worked well in Greece, so Merkel pressed repeat.

The old apparatchik’s argument about “reform from the inside” was clearly flannel; popular mandates are for the birds. As a result, the Brexit faction knew it had to be a clean exit, with one shot to the head. Sadly, Theresa May failed to realise that, and when the EU subsequently realised she had thrown her majority away, they had no reason to agree any deal, or not to expect another craven capitulation.

What of Greece now?

Well, it simply lost a big chunk of its economy (circa 20%) to creditors and demolished welfare payments and entitlements, for a generation. Was that fatal? Not really, life expectancy rose through that decade, as elsewhere in Europe.

The left largely destroyed its high-water mark, one-off advantage, but remains a mid-teens political faction.

The October 2023 regional elections saw even more regional governorships fall to the centre right New Democracy. This was along with a rip-roaring stock market in 2023 as the long rebound continued.

EU

And in Europe? Well, those June Parliament elections are getting interesting, Syriza will suffer more losses, and the gains by the centre right in Italy, Holland etc. are likewise yet to show up in Strasbourg. This provides context for this week’s defenestration of the French prime minister, for a near novice (at ministerial level). It seems this was a poisoned chalice for the big guns of En Marche, as the party are well behind Le Pen in the polls.

The European Parliament is such a mash-up of parties, and with limited real power, no change can be dramatic, but for once it could be at least interesting. The super-spending high regulating internationalist left, may get a setback.

Financial markets

Markets? I don’t think they ever get going till after Martin Luther King’s birthday is celebrated on Monday. Despite the need for news, the decline in global rates is baked in, and remains positive for equities, especially rate sensitive stocks.

You can stare into the Chinese abyss, but be careful that is does not stare back at you, you will see what you most fear or least know, as Nietzsche knew.

Happy New Year.

It is Not a Pipe

A long view this time : Has the price of capital changed for good? How bad is the UK position? Oh, and the unusual universality of colonialism.

A Far Off Galaxy

Let’s start with colonialism. I have been reading about the benighted past of Bulgaria (R.J. Crampton, 2nd Ed, CUP). A Bulgarian I know said that the country ‘has a knack for picking the wrong side’ - a little harsh, I thought. However, it has always existed as a colony, aside from a brief imperial phase around the last millennium but one, and before that when it equated to Thrace, almost as far back again.

Given the option, Bulgaria recently opted to join the Western European empires’ current formulation as the EU and NATO - the latter being the armed wing of Western thought. Bulgaria had suffered horribly under the Soviets, with a steady and ruthless coercion of an existing multiparty democracy, at a speed just enough to keep outsiders ignorant, or if not, passive.

That history gives me a whole new viewpoint, on the string of broadly similar states. The Balkans and The Middle East all appear in a new light, and indeed I start to comprehend the bitter sideshows (as they seem now) in both World Wars, over that same terrain.

The collapsing empires (Russian, Ottoman, Roman,) seem more influential than the current rulers in so many former colonial states. They are really not, as we think now, a series of nations fighting for ‘independence’. In most cases that independence is fragile to the point of being mythical, while the internal fissures are enduring. The cracks of nations within empires, not of states within a world.

Now You See It

One passage in Crampton’s work stood out “by mid-summer social and industrial unrest were widespread with strikes by civil servants. On transport networks, and despite the provisions of the law, in the ports and medical services. The government was forced to grant a 26% wage increase to all state employees, an action which weakened its attempts to control the budget deficit and inflation and which did little to impress the international financial organisations.”

Written about conditions just before another wrenching Balkan realignment last century, this rather made me stop and reflect.

A parallel with the UK?

Just how close are we in the UK to that edge? Lost in a warm feeling for individual strikers and their causes, and a very British willingness just to plough on, there still seems to be a real danger.

I am well aware of our great national strengths, in the arts, our language, higher education, science, heritage, even logistics and retailing - they are enduring causes for optimism. But long-term investors need to weigh up the recent damage, especially the loss of political capital by the “responsible” right, the high levels of debt and taxation, which coupled with low productivity, could also spell trouble, the certainty of ongoing nationalism and the unhealed rift of Brexit.

There is danger too in the probability of a Labour government, which however centrist the leader is, will have left wing factions to assuage. It is equally dangerous to continue our recent experience of minimal ministerial experience. I hope the change won’t be as bad as I fear, but it will probably be worse than I hope.

This remains a reason for the FTSE to be anchored to late 20th Century levels, despite almost every stock I research looking cheap. The fear of being still cheaper tomorrow rules.

Do Markets Care?

On the other hand, re-pricing capitalism after the decade of populist nonsense by central bankers does feel pretty good. If you have no cost of money and no reward for savers, financial gambling prevails.

All of this raises a key issue: is the apparent resurgence of speculation (the greater fool theory of investing) permanent? In which case investors should probably just watch momentum. Or is this most recent re-run of the last decade’s speculative phase, really transient?

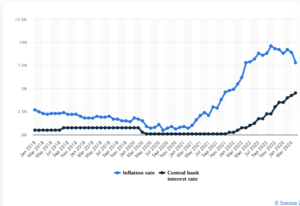

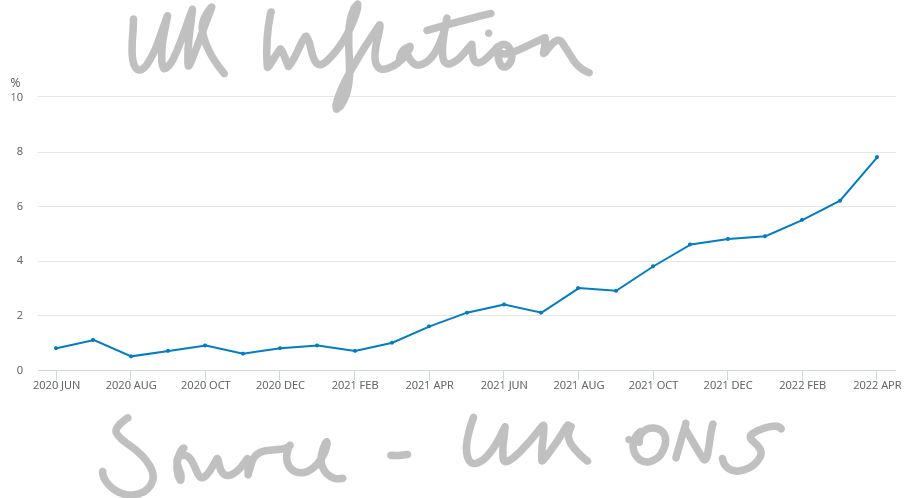

For a better view, see this page on Statista

As long as inflation exceeds the cost of money, assets will likely rise; the widespread return of real interest rates (a point we are almost at) should slow that down.

After that point what matters is cash flow, and whereas gambling will favour growth stocks, real returns come about when interest rates are high, but inflation is also falling. The gap matters and we are not there yet.

This is probably the crux of the next two years, and we doubt that having had a serene and slow drift towards recession, there is any reason either to expect a suddenly faster descent now, or really to expect the corollary, a sudden fall in interest rates, to offset a deep recession.

If rates stay high, but have indeed peaked and inflation declines, value investors should be in a better place. If they get it wrong, they are at least paid to wait.

As we have seen in the last twelve months, growth investors fuelled by borrowed money really do need a rising market, they get hit twice if it falls: both through a loss of capital and then the need to fund loss-making assets at real rates.

The Monogram View

Overall, our position has been that fundamentals should win, but we suspect momentum will win. Spotting the next momentum shift early, therefore remains a powerful driver of returns.

One narrative of 2023 (so far) is that the SVB crisis and stronger growth combined led to far more liquidity than markets expected. This fed into the gambling stocks, giving them momentum.

So, although the first half was not what we expected, the second half might still be. But it is just one narrative, and it may still be the wrong one.

Note : Further reading, for those interested in Bulgaria :

See also, The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Obolensky, Dmitri.

Bonds and Bullwhips

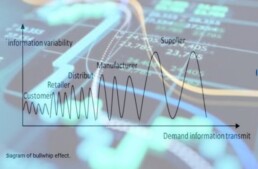

What are bonds for? Not always what you think. And the whiplash of the economy, (the bullwhip effect on all markets) makes recession both inevitable and meaningless.

Corporate bonds vs government bonds

So, to compare bonds - a corporate bond is issued to fund a project to produce a return greater than the interest and principal, and then pay the lender back. Much of the value lies in the assessment of how reliable that redemption is. Some of it is also whether the bond is cheaper or more expensive than a similar one, some of it is who is allowed to hold that bond.

But value lies in redemption, especially at the shorter end.

So, on that basis, what are government bonds? Well, they are there to achieve other objectives, seldom involving either redemption or a cash positive lifetime. It is largely accepted that they are a funding device to load debt upon future taxpayers, who luckily can’t vote. And the price of the bond is just what investors will pay for it.

Market rigging

Governments will therefore try to directly rig the market, to avoid paying too much interest, by for instance, mandating all investors and especially pension funds should hold gilts, their debts, on the gloriously fake grounds that they are “safe”. Well, just remember this year’s disastrous collapse, down by a quarter at the long end, with plenty of volatility too, ‘safe’ they are not. But the regulators and professional bodies still peddle versions of the old homily about the percentage of bonds in a portfolio should equal your age.

They can also apparently use the rate of bond interest to control inflation (so they say), so raising it (and devaluing bonds) if inflation rises, albeit the causes of inflation have little to do with the bonds (or bond investors). Then most marvellous of all, they can rig the price by easing and tightening their ‘quantitatives’ at will. Although no one is quite sure what a quantitative is, or indeed where it lives.

So, the government bond market turns out to be pretty much whatever you want it to be. To be contrasted with the weird and feckless equity, whose value can be, pretty much whatever you want it to be. Or indeed bitcoin, whose value….

A difference of degree granted, but less clearly one of substance. Rigged markets in any asset, make us nervous, and all markets are increasingly manipulated, to some degree.

What of bullwhips and earthquakes?

Well, both show a declining sinusoidal wave, that ripples prettily along and disappears. Whether it is the globe scratching its toe itch in Tierra del Fuego, or an irritated ear in Reykjavik, it is very jumpy. Where you stand now can be higher or lower than yesterday; it is erratic, chock full of faults, and crucially, not smooth and cyclical.

So, measuring whether you are higher or lower than last week’s datum matters little, if your fields have vanished into the sea, or indeed your sea has become a field.

So it is with recessions, after the shock we have had, being up or down two quarters in a row is trivial. Indeed, as that slick whipping wave races by, we will certainly be both.

Do changes in the Government bond markets matter?

And trying to decide whether the gyrations in the government bond market have any relevance to the level of the economy when the whole structure is bucking around, is slightly crazy. Nor are yesterday’s maps going to be of any use.

That is even assuming that the price of bonds has any relationship to anything except how little governments want to pay for their exorbitant debts. While I have not even mentioned the wealthy autocracies involved in the same game.

And that’s the market muddle we are in. The US Central Bank is playing old style economics, using the interest rate to control inflation - hang the cost of debt, that’s a problem for Congress.

But the UK and European Central Banks are playing new style, because they fear that the usual medicine will be disastrous for their rather sickly patients.

And US stock markets are using that funny old, discredited, yield curve to predict a recession that is by their definition (two down quarters in a row) inevitable, but ignoring the COVID earthquake which has upended all our old data and assumptions, simply because we have never had one like that before. The curse of econometrics is that we can only predict the future if it resembles the past.

EU stock markets

Meanwhile European stock markets have understood rates are not going up much more, because the EU would prefer to rig the market, so investors think they must have avoided a recession, which is equally a delusion.

And underneath all that is the great big chunk of molten sludge at the core, the vast irredeemable mass of government debt, where real yields are apparently staying submerged everywhere.

So wise men can select from all of that to predict that markets in debt and equity are going to go up a lot or down a lot, really as you wish. And they may all be right, at least somewhere on the globe.

Our own choices

But we still see no point in holding state debt, nor much in holding cash for too long. Corporate debt and equities, especially equities with a real value that you can figure out, maybe. We look at ones without state interference rigging the price, and with an ability to raise prices to hold margins, and which have a dividend yield. Those, we think, may still be attractive.

And we are not alone, many markets and stock prices bottomed out in October and are steadily inching up. Our own MonograM momentum models (both in the USD and GBP versions, a rarity this year) have triggered a re-entry into equites, and for once in a while, not US ones.

Something is shifting under our feet. So next year at least, is very unlikely to be like this year.

When we next write the calendar will have changed and no doubt many rate rises will have happened. But we doubt if the big themes will change much.

In the meantime, Seasons Greetings and a prosperous New Year, to all our readers.

Seeking an end to the turmoil

This market turmoil feels interminable, as asset markets stumble to find a firm footing and churn relentlessly. Instinct says that’s a time to buy. But there is so much happening, as this multi-year trauma unwinds, it is quite hard to know what.

Although we try to segment it, the key problem is the terrible dishonesty of politicians, who have bullied their citizens into an unthinking reliance on institutionalised theft on a grand scale and a belief that nothing really matters, as long as you have a press release to deflect it.

IT IS ALL STILL COVID

So, working through piles of annual accounts, as a pleasant distraction, (I have always enjoyed history), the one repeated theme, is of shrinkage, under investment, caution. This, in a way, is natural because COVID reset two years of global production, and indeed destroyed large areas of output and services. Which also makes it terribly hard to understand what “normal” is now.

Not helped by the piteous vagaries of those craving spurious accuracy. Big banks and resource companies seem overall just to want to carry on shrinking, which is odd as their results seem very good. But they are not. All that has happened is they took big write offs and reserves in 2020 (which were not needed) and that then reversed in 2021. However, the underlying business volumes fell, the trend to more disposals than acquisitions was unremitting; these are shrinking businesses.

To the populists who believe higher taxation lowers inflation (are they mad?) and indeed, to market commentators, this looks good, but it is really not, productive employment is shrinking too, workforce participation is not roaring back.

And with inflation we will again see plenty of “top line beats” or rising revenue, but that too is an illusion. And indeed, raised dividends. For example, Shell now proudly offers a 4% dividend rise, as if that is generous; last decade it was, but not now.

That is now a real dividend cut.

As we struggle with a badly damaged global economy, government policy is unremittingly wrong-headed: you wonder what we could do worse than the vast debt fuelled bubble after COVID?

But then we stumble on the idea of doubling or trebling domestic fuel prices. We do this to punish big energy exporters like Saudi Arabia and Russia. Only a simple clown could believe that will help us, and only a child-like vandal, that it will halt Russian armies. We take our own possessions out and smash them on the street, like voodoo dolls, because we are hurting and want others to hurt too. Nuts - it is tearing our own clothes in blind anger, but we ourselves are not the enemy.

Meanwhile, underneath all this noise, is the game up?

Is the expansion we have seen for two decades based on cheap Asian product imports, and low interest rates fuelling inflation in non-traded goods now done? The non-traded category is everything that can’t be shipped in. Land, services and the like that must be consumed, where they are provided. Although with that went quite a lot of imported labour consumption too, of course.

I keep wanting to write positively on China, but I simply don’t know. Is their COVID winter politically sustainable? Is it a massive pivot back to a closed state? Was the aberration their great expansion, and they are now reverting to being a hermit kingdom? Instinct again says no, who would reverse the greatest success story of our time? But evidence the other way just slowly piles up. Another giant nation seems slowly to be sliding towards belligerent stagnation.

And so much went crazy with the toxic mix of low interest rates, and excess liquidity. We may at last have learnt that if you have a blocked pipe, spraying it with gold is not a remedy. The pipe stays blocked, but everyone gets flecks of gold on them. Better (and cheaper) to hire a plumber.

WHAT WILL BE THE THIRD POLICY ERROR?

We certainly don’t see the recent bubble implosion reversing, for all the bluster, crypto, and concept stocks, feel to us like a long term drag on the indices, remorsesly lower.

The turn feels to be more likely in bonds. The fight is between a shrinking set of outputs, but rising prices and apparently rising consumption. As long as policy blunders persist, and they show no sign of ending; then the upward pressure on rates will also persist.

But we doubt that any conceivable interest rate rise can solve this inflation. In short, the fire must burn itself out or at least no longer be stoked up.

In which case posturing about a long run 2% 3%, or 5% rate is really guesswork. But that’s the big question. If it is 3%, we are already there, but there is no great market conviction on that. At least the belated but long inevitable addition of the Europeans to rate rises, should take some heat off exchange rates.

LETTERS I’VE WRITTEN

What about Boris? I was quite surprised at the swift and co-ordinated move to a no confidence vote. The Tory party is rubbish at a lot, but plotting it does do rather well. And also surprised at the vote itself. The rebels can not win, without a candidate that both factions like, that is the real Tory party and this odd “Cameron light” lot in Downing Street. Of course, Boris himself is already largely that candidate, talks right, acts left. Which means all sides hate him, but neither can replace him, for fear of the ‘wrong type’ of fake instead. Just what you want to be, you will be in the end.

There was also a fair bit of bile, stirred up by the media, and rather infecting what are loosely called the “activists”, who are anything but, but do bend their MP’s ears. They just want to dislike Boris and his lack of scruples, but also like the gifts he brings them.

They don’t want local trouble, so enough of those MPs voted against him, to keep their local associations happy. If that “terrible man” stays in office, they can at least claim they did their bit, but ‘others’ then let the side down.

Will Boris last up to the election?

Our core belief remains Boris stays in power long enough to hand over to Keir and Nicola. But perhaps we have rather less conviction than last week. We thought Keir was more likely to be in trouble, but perhaps the Tory plotters could be desperate enough to finally agree on a candidate? Either way this is now a lame duck UK government.

But then like markets, outside events may rescue it, it’s just we really can’t see how at present.

As for where to consider investing? Our MonograM momentum model loves the dollar, for sterling investors and for USD ones, increasingly just cash, and decreasingly the S&P, so long the global refuge.

But that is in no way a recommendation, just an observation; more detail on our performance page.