Caution: Bumpy Road ahead

Puzzle: World markets have whipsawed in the last few weeks, from high anxiety to an almost beatific calm. The VIX volatility index has dropped to pretty well a post-pandemic low. Which should mean we all agree, but on what exactly? Rising inflation, yes, but how durable, and caused by what?

And that, we all accept, will make interest rates rise, yes, but how high for how long? Markets we feel are, to say the least, fragile.

At the turn, we know that moves can be dramatic both ways, for markets.

Are we really seeing a labour shortage? The UK truck drivers’ situation

What we see now is not a labour shortage, and hence political talk of stemming migration and higher wages is well off target. What it is, in part at least, is a failure of the routine operations of an incompetent government, something politicians typically don’t want to discuss.

The government has insinuated itself into so many areas, with its complex regulations, that the market economy now lies ensnared in myriad interlocking regulations, backed up by a deeply entrenched blame culture (and its friend the compensation economy).

To take one example, there is no shortage of truck drivers, but there is a shortage of qualified, approved, signed off and regulated truck drivers, because as part of the destructive lockdown, the government just halted the conveyor belt of required testing and approvals.

Truckers’ wages have for long been too low, of course, especially for the owner drivers in the spot market. What we have is not a labour shortage, it’s a paperwork shortage. The difference is vital for how enduring inflation is. A new driver will take a couple of decades to grow, but clearing a paperwork jam, a few months. One is enduring, the other transient.

Withdrawal of older workers from the labour market

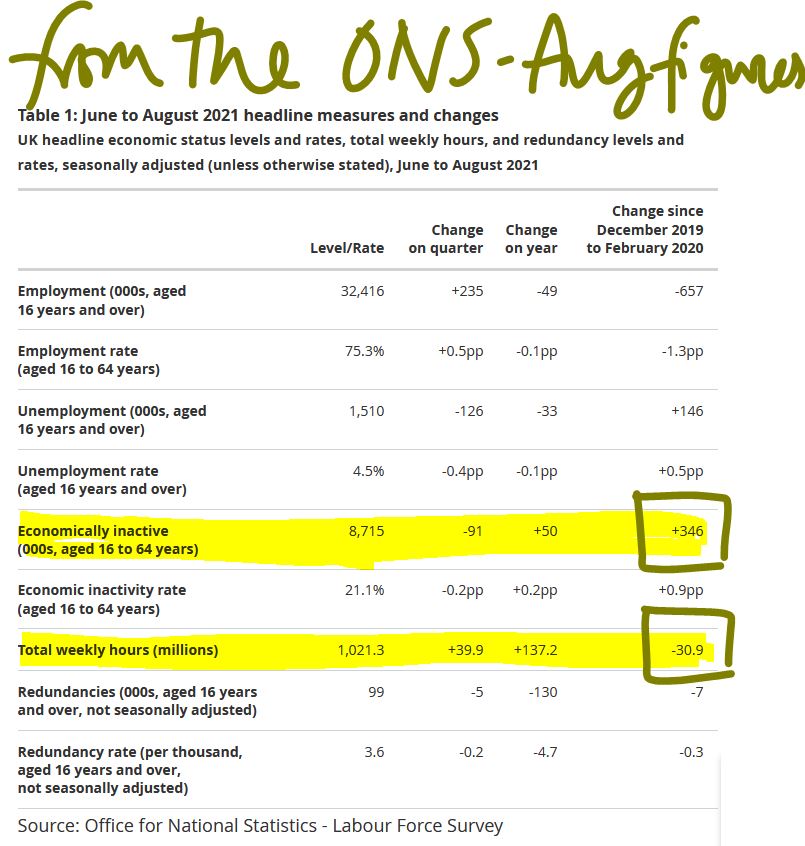

Work after all is something of a habit: once it is lost, it can be hard to understand why it existed. So, we see a marked increase in older workers in the UK who have just withdrawn from the market (Some thirty million fewer hours worked - see figure below). That too is not a labour shortage as such, they all still exist.

But if work was of marginal benefit to the worker, and the costs to resume work (actual or psychological) are high, disruption will cause the fringe or marginal job to be unfilled. Yet again more in the transient column than permanent.

Someone will waive the rules, or the government will notice, well before all drivers get paid high enough wages to cause embedded inflation. In any event articulated fuel tanker drivers tend to work for big employers, with good conditions, and are well organized. They have to be, after all they drive mobile bombs. The spot operator on a rigid rig is in a different market.

Inflation will most likely be transient

So, if it is not an actual labour shortage, it won’t cause wage inflation, and will be transient. Some other areas reliant on highly skilled older workers will continue to see standards fall, but generally younger workers will over time fill those slots and gradually acquire those skills. And it won’t be a long time.

Our view from way back was of 5% plus inflation and labour markets that struggle to clear this year. We were wrong to not foresee the failure of regulatory processes to keep up. However we still do see a permanently higher post COVID cost base and therefore in certain sectors, a large amount of marginal productive capacity are likely to be withdrawn from the market.

With a banking system that still struggles to offer commercial finance to the SME sector, because of excessive regulatory caution, there are swathes of jobs that have simply gone. So that labour will in time be redeployed. The current concern is that many of these workers show no desire, or ability under current conditions, to return to the market. But when they do, the capacity that has been destroyed will slowly return, and once more drive down prices.

Nor should we forget just how much the Exchequer loves inflation, as fiscal drag, their beloved tax on higher prices, smooths away so many budgetary blemishes. They will let it go, if they possibly can.

Commodity prices

On the input side we do still see commodity price rises as transitory, at least within the energy market. As others have noted much of that too is regulatory failure on a grand scale, not a true shortage. Price fixing by the state is a notoriously foolish concept, as we learnt in the 1970’s.

There are a number of other supply factors at play too, but while some will recur, most are temporary.

How long do we think the inflation spike will last?

So yes, inflation will spike, and yes it will stay elevated for much of next year, but no, we don’t see it as necessarily durable, once COVID restrictions and related behavioural changes vanish.

We are still pretty certain that the political costs of aggressive interest rate rises will outweigh any perceived price control benefit. As long as some Central Banks hold off rises, it will be very hard for others to do so, without sharp currency moves or bringing in formal exchange controls. That would in turn spook markets far more than rate rises.

The next phase of markets

All of this says to us that a major market dislocation, despite the benign signals, lies ahead in the next six months.

Markets shifting rapidly are more a sign of uncertainty than of a new degree of confidence, and we simply don’t trust it. We see inflation as apparently out of control, but no significant interest rate rise response is feasible. That can feel like stock nirvana, but also like investor purgatory, as you have no idea what is or is not a sustainable profit.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd