Too chilled

Markets seem far too relaxed about world elections; we suspect from ignorance. Logically if you move from certainty to uncertainty (with a range of possible outcomes) you should adjust your level of risk. India has already shown some of the volatility of the 'wait and see' approach.

Too hot?

So, we start there, where prior confidence in an enhanced majority for Modi, was well wide of the mark, he ended down 63 seats at 240; a majority is 272. Some of that chaos is the electoral system, and some of it the ban on opinion polls - although some accurate information inevitably crept out, despite restrictions, but international investors did not pay much attention to it.

So, when the exit polls announced all was well, the market rose, only to reverse hard when the real result emerged within a few hours. Although then buyers came back in, and we ended up flat.

From this website – date published : 8th June 2024.

On a call with local managers, (and the options for investment in India are wider than you might assume) clearly something had changed, one was almost pleading with the international audience not to take money out. Very little spooks other fund managers quite like being repeatedly asked to not redeem.

The Congress Party has almost doubled its seats, from 47 to 99, a strong result. The other beneficiary was the Samajwadi party, nominally socialist, with a strong presence in Uttar Pradesh, a vast Northern state. They went from 5 to 37 seats and are very much in Modi's BJP territory.

India has always had strong states, with the more populous ones often having a local ruling party, which has been around for ages. So, this is a reversion to the long term normal.

In house collage of a state by state analysis of Indian share ownership percentages

But that is what scares investors; coalitions nearly always break down. There was also damage to the Index from the Adani group of interlocking holdings (long hounded by Congress for alleged corruption).

A weaker Modi

That allied with the long-standing fears about political corruption, uncertainty of policy and no national enforcement, is an unwelcome reminder that Modi is now in his last term. Hopes that stability will follow him, rather than a swing back to the broken past, always felt optimistic.

The commonly voiced issue is that a weaker Modi will have less ability to drive structural reforms and will find it harder to resist welfare payments, and labour demands. Historically, some of these payments and concessions reach the poor, either in higher consumption or better services, but a great part gets stuck with middlemen. That should be less of a problem now, as a result of reforms already implemented, putting in a national bio identity scheme and almost universal individual banking services.

We will see.

While generally expecting strong growth to persist, we are now more cautious about signs of the lost consensus, into the medium term.

The UK - far too chilled

Which brings us to the farce that is a UK General Election, where such discourse as there is has been about whether families are or are not facing a £2,000 tax hike (or roughly 20% more for those on average earnings). Not knowing where they live, or how they spend their money, or indeed how they will adjust to high taxes, you can never tell these things with much accuracy.

This comes with minute (and futile) attempts to list every one of the myriad ways that the assumed tax hike won't happen and extracting a "pledge" from all parties not to raise them. As if all Chancellors do not have multiple ways to raise revenue, carte blanche to create new charges, and a great ability to lie or concoct exceptional circumstances to hit us. Sunak of all people should know that.

Yet most voters are thinking, is that all? Is it enough? We know that existing service demands are not being met and that no party seeks to resist the endless demand for expanded services.

I doubt if growth will save us either: we are close to the point where those that can take investment elsewhere, have left, and no sane investor would now invest, without substantial state subsidy. So, we are simply building up to an inevitable budget crisis in the medium term.

There are a few who hope that change will be its own reward, maybe, but we can't really tell much until after the first Budget, (Labour have pledged to revert to just one a year), and a couple of Parliamentary sessions.

Just waiting and hoping is illogical. Markets do just that, though.

Frozen in the US

Which brings us finally to the USA, the Presidential election feels (to me) fairly easy to call, but how the US Congress and Senate go, does not; the resulting power (or otherwise) of the President is less easy to predict. It may be that we get a split between parties again, which markets like, and it feels unlikely (but possible) that we end up with constitutional change, which markets certainly won't like.

The current Federal Reserve Chairman will be in office for all of 2025, but almost certainly not beyond that, and who replaces him, will figure high on the consequential concerns, as unlike other Central Bankers, he sets the global tone. Powell is not popular with either of the spendthrift presidential candidates seeking office. Nor will he be trying to get reappointed. He has been an odd and erratic champion for the dollar and sound money, but he has been that.

I am not sure other elections are so consequential, the European Parliament has hopefully done its worst already, while investors in both Mexico and South Africa are starting from a low base of limited ambition.

So, to us, the question is how long to follow benign short-term themes, while such dramatic shifts may be hitting us within six months.

Inactivity from ignorance remains attractive, but is it wise? At some point in the interim, markets will probably decide not.

All kinds of everything

We move towards the end of the year with a great deal of challenging uncertainty and big calls to make, on inflation, China, US Politics, whether interest rates are pegged, and a few political issues. The temptation to sit it out and come back after Burns Night, is intense.

A lot of things will be clear then: the severity of the winter, and hence fuel prices, also of the EU COVID spike, the nerve of some Central Banks and who leads the largest one, and how the Beijing Olympics will go. All are potentially significant matters for investors.

Few of these issues are surprises, which is good, indeed we see advanced economies as being in fairly stable shape, but badly damaged by populist politicians, who can’t face telling voters that ‘nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever could’.

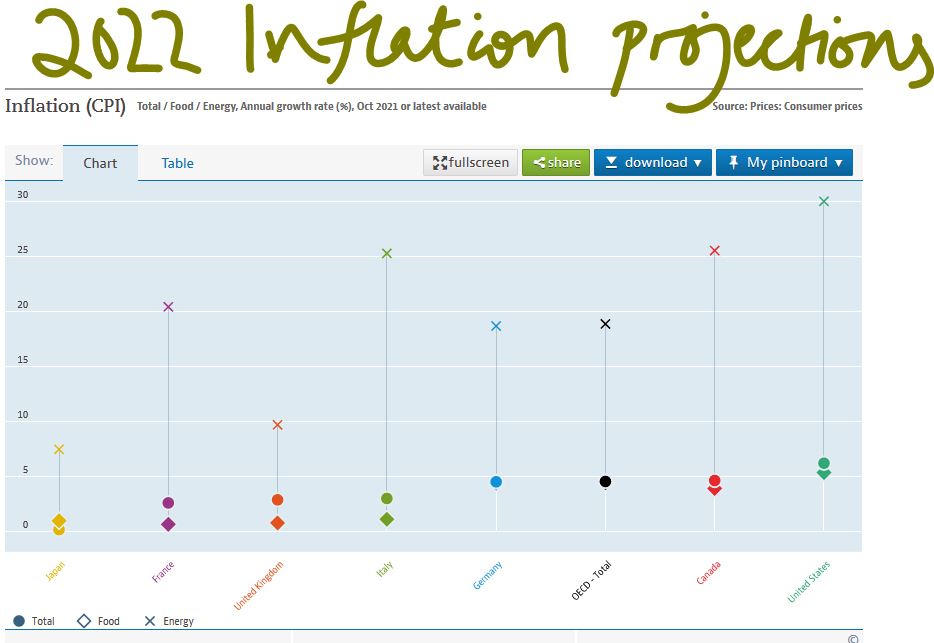

Inflation

So, on inflation, we took some flak back in the Spring for talking about 5% inflation, but we regard that as pretty conservative now.

From the OECD data here.

We see it as structural too, not related solely to excess demand, supply chains or energy prices. All of these matter, but the last two are indeed transient, and excess demand is within the power of the fiscal and monetary authorities to affect. The real trouble is both the lingering and severe harm COVID is causing to productivity, especially in the service sector and in a public sector still too reliant on overmanning and allied with that, the curse of politicians trying to exploit the pandemic to pay off their chums.

Our conclusion is that we will have higher prices at least for the next two quarters and possibly all of next year. Critically Central Banks will most likely be powerless to prevent or reduce that, without bringing the house down.

Broken China?

One cannot but be envious of the performance turned in, yet again, by Scottish Mortgage. The half year gains are massively from one stock, Moderna, and then a broad raft of e-commerce and big data plays. So, really, they just continue to surf the NASDAQ run. By contrast their big cap China positions generally damaged performance but have not yet been visibly trimmed. Although China does drop from 24% to 17% of their NAV, which is significant, with North America rising from 50% to 57%. (I should also mention we don’t hold a position in this stock and have not had one this year.)

So, NASDAQ strength allows them to survive what for most fund managers has been the poison of owning anything in China this year. A decision we took, guided by our momentum models, very early.

We also note the manager’s viewpoint, which broadly aligns with a view that what Beijing is doing, is what the West should do as well, in attacking and controlling big tech platforms and their associated excesses. Telling the biggest companies to also do more to reduce inequality and cure social problems hurts profits; but they still see both as not unreasonable requests and they claim big Chinese companies are already willingly complying.

Yet for all the apparently cold rationality of the Scottish Mortgage viewpoint, we do understand it, and do see China trashing their participation in areas of global commerce and capital markets as an odd piece of self-harm, if it is really their aim, not just an ill-thought-out consequence of domestic actions.

So, we see the set back so far in China stock prices, as based on the possibility of the area being uninvestable, like Russia, but not yet on that certainty - see the how strong the trade figures are even with India, a so-called political antagonist. But tipping over to uninvestable would be a market shock and again we inch closer to that, with each diplomatic spat.

United States - and the Fed Chairman

The big US call, and again we signaled this as critical a while back, and actually well before the US Presidential Election, is about Powell. My sense is removing a competent Fed Chair for purely partisan reasons would be damaging to markets and the dollar. But the pressure on the ailing Biden to do just that feels intense, and I am struggling to see who in the White House will have the maturity to stop it, if Biden caves in.

Would a new Chair do things differently? Might markets push harder still for a rate rise and the dollar, short term at least, suffer? For now, re-appointment is still expected, but the odds on a shock are shortening.

Interest rates

The Bank of England is also, quietly in the midst of a storm, it is not actually independent however hard it claims otherwise, it relies too much on Whitehall just to survive, and, in a way, can’t do anything meaningful on inflation anyway. Still a rate rise, even a notional one, would show it is still awake. It makes little sense just now, but as a symbol might yet happen. To us it simply adds emphasis to the political chaos overtaking Johnson and the ongoing shift towards an institutional alignment with a Starmer government.

Material interest rate rises (so returning us to positive real rates) during 2022 therefore still feel impossible. Indeed, German rates have once more flirted with changing the nominal sign, only to collapse back into negative territory.

To sum up - where does that leave us?

Well curiously, mildly bullish. We may not much like the position, but who cares about that, our task is to make money for investors. We also have had a think about what rescued investors from the COVID slump, on the basis that a future sharp inflexion in interest rates could look much the same.

What we see is the power of real growth, not the flotsam of cash hungry concept companies that can never pay a dividend, but fast-growing, broad-based technology – following that has been the winner for a decade. We do want to call time on that, partly for the nonsense and scams it tugs along behind it, but we still struggle to see the turn.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

Which is the Leviathan?

This is a week to ponder the role of private equity in portfolios, in what may be an early phase of a great investment and technological explosion. There seems to be no sign of higher interest rates and a stubborn refusal by Central Banks to care much about inflation. The talk of a UK raise always looked to us like a head fake which we ignored.

Spotting good and bad private equity

So first to private equity, a beast that comes in many guises, not all benign from an investor viewpoint. All liquidity fueled equity explosions come with a heavy loading of chancers; Bonnie and Clyde’s rationale for bank robbery remains valid.

Good private equity relies on management being superior to that of their targets. This can be in their analysis, their execution, their swiftness of foot or their innovation. All of this generally flourishes away from the hidebound inertia of many listed companies and their professional Boards of tame box tickers.

Bad private equity uses accounting tricks, the malleable fiction that the last price is the right price in particular, and the terrible phrase “discounted revenue multiple” which is a nice conceit for “never made a profit”. All of these share the same vice of management marking their own work.

So, we struggle with the likes of Scottish Mortgage and its little array of unquoted Chinese firms, the alphabet soup of non-voting share classes and love affair with management. Maybe they are that skilled, but nothing that looks like a real two-way market is evident to us, in many of these valuations. We have by contrast long admired Melrose Industries for their quite ruthless devotion to turning over their investments, good or bad and stapling executive pay to actual cash realizations paid to investors.

Where we stand – given our strategy

For an Absolute Return specialist there are added constraints: we want to hold under twenty positions altogether and all in ones we can sell tomorrow afternoon. And we like holdings where valuations are transparent, there is no gearing (there is usually quite enough in the private equity deals already), and you can pick them up for a fat double digit discount: oh, and we do like a yield too.

So, we are looking for big, listed options with hundreds of high-quality funds bundled together and for any yield, a bias towards management buy outs. We are certainly not at the venture capital end, with silly pricing, high fail rates, unrealistic managers, and not a decent accountant in sight and aspirations to change the world. Met those, invested in too many, and donated more shirts off my back than I care to enumerate to their serial failures and inexhaustible funding rounds.

But there are good things about Private Equity, one is that in a rising market, it can be like clipping a coupon. The accounting rules require them to be backward looking, so coming out of a trough they are typically reporting on valuations that are three or four months old, which in turn reflects business activity up to six months old. As they trade at a discount of typically 25% or so, you can buy today at a 25% discount to the value of the business they were doing in the spring. There are no guarantees, but for most, that was a lot worse than current conditions, so today’s price is simply wrong. This is a time machine that lets you buy now but pay at old prices.

Watch for built in volatility in private equity

These lags are complex, the reference points are often public market valuations, and so there is volatility built into them. While in an Absolute Return fund, not only are choices limited but the overall exposure must be too. However, in those rare purple patches of fast recovery and expansion they are excellent for performance.

What kills these bonanzas off is tight credit. In part they need debt for trade, but also their realizations rely heavily on it. A closed IPO market does them no good (just as they enjoy an exuberant one). That is a risk, as liquidity starts to tighten, that this will hurt, but as Powell and the Bank of England both showed, there is no political appetite for that just yet.

The UK and US on taming the leviathan

Indeed, Sunak’s UK budget yet again feels reckless, devoid of any discipline and with every department cashing in. Government spending is predicted to rise to 42% of GDP by 2026, a fifty year high. Healthcare alone is predicted to have grown by 40% in real terms since 2009 (both estimates from the oddly named Office for Budget Responsibility). At that level of loading, it is inching closer to hollowing out the entire budget and causing it to implode. (Leviathan was just such a creature “because by his bigness he seemes not one single creature, but a coupling of divers together; or because his scales are closed, or straitly compacted together” feels an apt description of this new giant state apparatus.)

But that gamble means there is no room to pay higher interest rates, or the economy will be reduced to a double-sided monster. The one face devoted to raising debt and levying taxes and paying interest, the other to feeding out of control public spending, with nothing left in between.

Thanks in a slightly odd way to a Democrat Senator, America has avoided throwing itself under that same bus, but with no effective political opposition the UK is now powerless to resist. Sterling’s relentless decline from the summer high and a FTSE 100 index still below its pre-COVID peak signify what markets feel about all this.

From the London Stock Exchange graph

So, while we were more bearish than we have been all year, in terms of asset allocation, at the end of October, we have yet to call time on the Private Equity cycle, that has provided such a powerful boost this year. It still feels good value to us.

Of course, we recognize too, that the populist fear is of the wealth creators and an opposing adoration for wealth consumption. Unlike politicians, however, we are tasked with producing real results not vapid dreams.

I guess we can each choose which to regard as the leviathan – the burgeoning state, or private equity.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

Caution: Bumpy Road ahead

Puzzle: World markets have whipsawed in the last few weeks, from high anxiety to an almost beatific calm. The VIX volatility index has dropped to pretty well a post-pandemic low. Which should mean we all agree, but on what exactly? Rising inflation, yes, but how durable, and caused by what?

And that, we all accept, will make interest rates rise, yes, but how high for how long? Markets we feel are, to say the least, fragile.

At the turn, we know that moves can be dramatic both ways, for markets.

Are we really seeing a labour shortage? The UK truck drivers’ situation

What we see now is not a labour shortage, and hence political talk of stemming migration and higher wages is well off target. What it is, in part at least, is a failure of the routine operations of an incompetent government, something politicians typically don’t want to discuss.

The government has insinuated itself into so many areas, with its complex regulations, that the market economy now lies ensnared in myriad interlocking regulations, backed up by a deeply entrenched blame culture (and its friend the compensation economy).

To take one example, there is no shortage of truck drivers, but there is a shortage of qualified, approved, signed off and regulated truck drivers, because as part of the destructive lockdown, the government just halted the conveyor belt of required testing and approvals.

Truckers’ wages have for long been too low, of course, especially for the owner drivers in the spot market. What we have is not a labour shortage, it’s a paperwork shortage. The difference is vital for how enduring inflation is. A new driver will take a couple of decades to grow, but clearing a paperwork jam, a few months. One is enduring, the other transient.

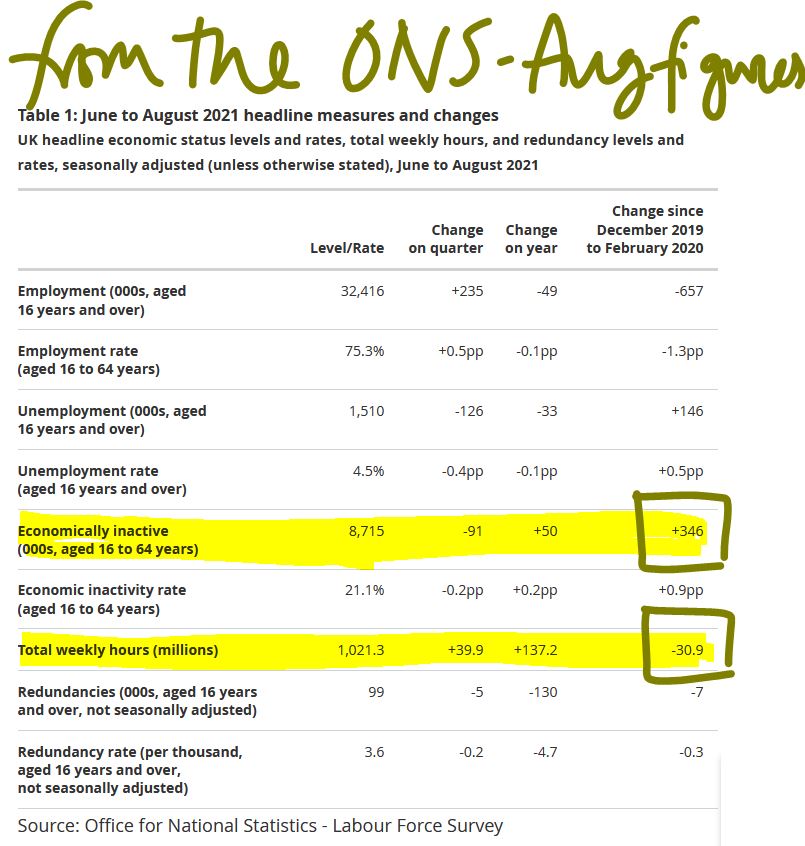

Withdrawal of older workers from the labour market

Work after all is something of a habit: once it is lost, it can be hard to understand why it existed. So, we see a marked increase in older workers in the UK who have just withdrawn from the market (Some thirty million fewer hours worked - see figure below). That too is not a labour shortage as such, they all still exist.

But if work was of marginal benefit to the worker, and the costs to resume work (actual or psychological) are high, disruption will cause the fringe or marginal job to be unfilled. Yet again more in the transient column than permanent.

Someone will waive the rules, or the government will notice, well before all drivers get paid high enough wages to cause embedded inflation. In any event articulated fuel tanker drivers tend to work for big employers, with good conditions, and are well organized. They have to be, after all they drive mobile bombs. The spot operator on a rigid rig is in a different market.

Inflation will most likely be transient

So, if it is not an actual labour shortage, it won’t cause wage inflation, and will be transient. Some other areas reliant on highly skilled older workers will continue to see standards fall, but generally younger workers will over time fill those slots and gradually acquire those skills. And it won’t be a long time.

Our view from way back was of 5% plus inflation and labour markets that struggle to clear this year. We were wrong to not foresee the failure of regulatory processes to keep up. However we still do see a permanently higher post COVID cost base and therefore in certain sectors, a large amount of marginal productive capacity are likely to be withdrawn from the market.

With a banking system that still struggles to offer commercial finance to the SME sector, because of excessive regulatory caution, there are swathes of jobs that have simply gone. So that labour will in time be redeployed. The current concern is that many of these workers show no desire, or ability under current conditions, to return to the market. But when they do, the capacity that has been destroyed will slowly return, and once more drive down prices.

Nor should we forget just how much the Exchequer loves inflation, as fiscal drag, their beloved tax on higher prices, smooths away so many budgetary blemishes. They will let it go, if they possibly can.

Commodity prices

On the input side we do still see commodity price rises as transitory, at least within the energy market. As others have noted much of that too is regulatory failure on a grand scale, not a true shortage. Price fixing by the state is a notoriously foolish concept, as we learnt in the 1970’s.

There are a number of other supply factors at play too, but while some will recur, most are temporary.

How long do we think the inflation spike will last?

So yes, inflation will spike, and yes it will stay elevated for much of next year, but no, we don’t see it as necessarily durable, once COVID restrictions and related behavioural changes vanish.

We are still pretty certain that the political costs of aggressive interest rate rises will outweigh any perceived price control benefit. As long as some Central Banks hold off rises, it will be very hard for others to do so, without sharp currency moves or bringing in formal exchange controls. That would in turn spook markets far more than rate rises.

The next phase of markets

All of this says to us that a major market dislocation, despite the benign signals, lies ahead in the next six months.

Markets shifting rapidly are more a sign of uncertainty than of a new degree of confidence, and we simply don’t trust it. We see inflation as apparently out of control, but no significant interest rate rise response is feasible. That can feel like stock nirvana, but also like investor purgatory, as you have no idea what is or is not a sustainable profit.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

POWELL / GOVE : DROPPING THE PILOTS?

Jerome Powell looked ill at ease twice at his Wednesday press conference, with neither occasion related to monetary policy. While in the UK, Gove’s sidelining is the end of any chance of reform from this UK government.

Oddly when asked about his ‘hand in the till’, for bailing out his own family position in US Municipal bonds, Powell barely flinched. So why then is he worried?

The Powell press conference - what riled him?

He should be upset that the unemployment rate among black Americans is twice the level it was pre-COVID, at over 6% still. Given his pledge to hold the money taps open till that is fully recovered, which has for a while been clearly impossible without traumatic inflation, harming those same citizens, that should concern him.

This has long been Powell’s talisman to ward off the hard left, who are bent on two great goals, firstly taking over the reins of power by ejecting him and secondly finishing off Wall Street, as they so nearly did under Obama. Kamala Harris has not been in that triumphant position, at least not yet, so do the left really want to accept another deputy?

I doubt it.

So, the two questions Powell was riled by, were one about the new deputy governor, who has in this case the power to drive the regulatory agenda, mandated under Dodd Franks. Now, if one of Senator Warren’s acolytes can be inserted there, Powell will find life immeasurably harder. But for markets worse still,(the second question) was if Powell himself is chopped (Trump looked into it) before the recovery is complete. A weakened Biden has few other goodies to offer, if his portmanteau bill to throw $3 trillion of cash to his voters fails, scrapping a top Trump nominee at the Fed, might be the political trade-off.

While for Powell, as this all starts to get rather dirty, I could see him for the first time, asking if he was really that bothered.

The US recovery - stimulus, markets, and minorities unemployment

The rest was all telegraphed passivity, still pumping enormous stimulus into the US economy, long after the recovery is running hot.

The US 10-year bond resumed its gentle lapping sound against the low-rate rocks, the storm of inflation roared on overhead, and the shadow of crossed fingers, fell on every vault.

The market has turned, in the US at least, from worrying about ‘when’, to guessing ‘how high’, with, given the global malaise, some confidence that “not very” is the answer.

Chop the Chair of the Fed, and that delicate illusion shatters. While whatever his politics, shipping Jerome off the transom, will hurt those same beleaguered minorities most. We should never underestimate the zeal of a convert, and he is that.

Sidelining Gove

We have not seen that kind of zeal on these shores for over a decade. True, various short-lived moneymen have breezed through ministries, failing to unpick their form and function, scattered management speak and chums’ contracts around equally liberally, and left.

But lifting the drains, sorting the plumbing, fixing the boiler type reform, no, Gove is oddly (because he was useless at it) the last of those to fall. But he had the great merit of scaring people and driving legislation, which with the stodgy morass of public sector spend, is part of the battle. But the idea that he can either help on “levelling up” (which is just a catch phrase, and always will be) or pacify the Celtic fringe, hungry for real power (and unaware it does not exist) is risible.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet Office is quietly stripped of ministers, to be put back in the box marked “too difficult” once more.

A parallel with Chinese policies

This is like selling the inhabitants of East Turkmenistan down the road for some of Chairman Xi’s foggy promises on future coal fired power stations. It would be sad if it weren’t true.

Although China is now helping us return to a land beloved by investors, where money is scarce and hence actually earns a return. While risk still clearly comes in many forms; including Marxist morality, that is, if such a thing exists.

Big corporate failures do at least achieve that heightened risk awareness.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

:) You might already know that 'dropping the pilot' is a famous cartoon by Tenniel from 1890 when the Kaiser dropped Bismarck.