Good intentions

Two quite technical topics this week, hinged on the persistence of old viewpoints on current markets: pricing in UK stock markets, and China, and how we might look into emerging market funds. Plenty of good regulatory intentions, but rather less than welcome outcomes.

FIXED ODDS

Little in the debate on UK markets has looked at the major role played by an increasingly poorly performing small UK bank, Close Bros. Even when it was doing well, it felt odd to have a vital market role being undertaken in a backwater, but as its capitalisation dwindles, the core task of equity market maker, which it provides, seems oddly misplaced.

In smaller UK stocks, we therefore still have a ring holder who, it is said aligns buyers and sellers’ interests. Not mine.

Given the fortunes at the disposal of state banks or indeed the London Stock Exchange, why is Winterflood (a part of Close Brothers) still trying to provide this vital service in the style of an old-fashioned bookie?

It matters greatly, because in many UK stocks and investment trusts, the wide bid offer spreads make dealing almost impossible. If you are eking out a high single figure return, and in these markets not doing badly to do so, Close Brothers scooping 10% off a single trade, in the bid offer spread, is pretty lethal.

With them restricting trade, liquidity disappears, without liquidity so does price discovery, and it is not a stock market any more.

Close has itself also suffered a number of hits lately. It is a hotch potch of old merchant banking activities, along with an expensively acquired asset management business, plus a shocking venture into litigation funding that might ultimately (it is itself a matter for litigation) cost almost as much as they paid for it.

While just lately the FCA has been asking (dear CEO…) about insurance premium finance, oh, and Close has a lot of motor finance too, an area of recent expansion, but also another hot spot for the FCA, after issues on commission. The latter Close has known about for a while, it was a disclosed risk in their last accounts.

All places where margins are quite high, perhaps in the view of the FCA too high.

From: Close brothers website – section on ‘who we are’ - their business model.

Given the lack of any announcements, the 40% share price decline in Close (CBG) over six months, to levels seen just after the GFC, is remarkable. Perhaps this benign graphic is not quite the whole picture?

Premium financing is ironically a good business, because the FCA’s wide and unpredictable view of its own remit makes financial services insurance premiums rather high, but that’s another story.

And market making is run as a bookie, not as a market utility. Winterflood itself can be taking a long or short position. So, investors must fathom both the share price, and which way their market maker is facing. In big stocks with lots of choices that’s all fine and pretty transparent. But in small ones, they can look (and behave) like the only game in town.

And it looks as if last year, they possibly went too short in the autumn. So, when the market turned on a dime in November, a fair bit of short covering took place, prices leapt, in places by over 20% and spreads opened out. And market size dwindled to penny packets.

It matters how? Well, you can get ripped off to deal in smaller UK stocks, where smaller is up to about £300m, and the price can be “wrong”, volatility increases, and liquidity goes. Do companies or investors like any of that? Nope.

It is notable that their trading profits in this area seem to far exceed both their gross (long and short) and net (long less short) positions.

Every big company was small once, and if you choke off the supply you get an ossified market, like the current moribund main FTSE index.

Perhaps the FCA could start to look more at best execution and market depth, and less at arcane ways to double count costs, or ‘protect’ those trying to enter the primary market from strict rules. This interview with Witan makes a reasonable case for looking after the secondary market first, not just the big IPO’s, with their juicy listing fees.

Investor protection is about investors making money, not about them losing it as cheaply as possible.

CHINESE BURNS

After our piece last time, we have been looking at Emerging Market funds ex China, because far from being the great hope of EM investors, China (and not just the PRC, but also Hong Kong) has become the rock that shatters fragile performance.

The role of benchmarking

There are several structural problems in EM funds, one is the role of benchmarking. A good idea at one time, it allows investors to compare performance to something specific. But it has become quite expensive (guess who pays?), as benchmarks don’t come cheap, if you now have to have them.

It also rather neatly points out to investors, when an index fund might do a better job than active managers, and worst of all, especially with the oddly amateur directors of most UK investment companies, leaves them ‘hugging’ or enslaved, to the benchmark. For good reasons in one sense (you don’t get fired for just about beating the benchmark) but for bad in others (all the funds are boringly similar). They just make the same mistakes together. And a beaten benchmark, that is itself falling, means the investor still suffers losses. I have yet to meet an investor that liked those.

The impact is both direct, so you can’t find India funds without Reliance Industries (the biggest stock), for example, and indirectly so as to “generate alpha” funds take bigger risks within a market, rather than have a below benchmark position in that market, even if all their analysis says they should just quit that particular town. Which is why funds find reasons to linger in bad neighbourhoods.

Another bias that hits the EM sector (which for a decade now has flattered to deceive) is that their stock analysis is focused on stocks they have held, while the investor wants to hear about stocks they should hold.

So, a fund manager typically gives a detailed list of analysts and companies followed by their firm, and it is full of what looked sensible when all those analysts were hired. So, in EM, there are stacks of China analysts, of organisations based in Singapore (the preferred offshore China centre, after Hong Kong got too hot), hundreds (if not thousands) of Chinese stocks covered, but all the buying is now into India. With quite nominal stock coverage; and hardly anyone based in the country.

Just as to a hammer, every problem is a nail, so to those EM analysts every opportunity is in China. Until outfits like Janus Henderson and Templeton stop having toolkits full of hammers, they won’t be able to stop breaking investors’ hearts with China. Nor will investors realise quite how much this infects their performance.

This will slowly correct, but small funds that can exit China totally in a week, and have a global remit, with no equity benchmark, dare I say it, have quite an edge.

It is a vast and nuanced space, Lazards provides a good overview.

And it is not just EM specialists, we looked at Ruffer of late, it has got broken China littered amongst its portfolios.

So, we worry that the Christmas rally looked broad based, because of a bear squeeze over a range of stocks, that then reversed with early January selling, based rather more on fundamentals. In which case 2024, so far, is in danger of looking more like 2023, less like the cyclical turning point many hope for. We do see earnings falling, of course and then ultimately rate cuts rescuing valuations. But ultimately may be quite a while.

Boris finally quits, and 'Quality Growth'

Boris finally quits: the loss of his Chancellor clearly made this inevitable. We also reflect on the London Quality Growth Conference, held in Westminster last month. It implies a very US bias, driven by two US universities, that seem to dominate much of UK investing and indeed public policy.

First as tragedy, then as farce

So, it is over. The absurd repetition of the same error and the same apology passed from tragedy to farce.

Clearly the belief that you fight inflation and unpopularity, by bankrupting the country with printing money, had also simply become too much for Sunak. That was the fatal blow. Let us hope the next leader is less of a deranged populist. In the real world what is popular seldom overlaps with what is right.

We will skip the look backward, over his flawed career, skip the look forward over the seven dwarves, and fervently hope for a different set of economic policies by his successor. It sounds as if there is plenty of time for a long summer of speculation. The likely candidates are less than attractive, let us say.

How might the UK market respond?

Nor can I fathom a market response to a change of leader in London: bullish that it is over? Or could it be bearish as we don’t know what comes next, or indeed bearish in that it surely strengthens the opposition?

While we felt the Old Lady moved far earlier than others (late in 2021) because of UK fiscal laxity, we see no reason yet for them to back off their August rate hike. Politically it is hard to stop and start interest rate moves, while just repeating a previous measure in mid-summer will look innocuous. I suspect that’s true for September too, but that feels a long way off. And I do note, that as we predicted, the great spike in corn and wheat prices has taken just one growing season to unravel, as farmers react quickly, by adjusting cropping patterns, knocking out another justification for any more price rises.

A weak pound is also importing inflation, and the Bank has to make a stand somewhere, but 1.19 to the dollar feels too early, 1.09? Pressure will start.

Alchemy Unchained?

We turn now to ‘Quality Growth’, an excellent conference and well presented with a dozen first rate managers from the US, UK, Europe presenting.

But it led me to ask about the underlying assumptions of the ‘Quality Growth’ model.

Firstly, there is the Santa Fe school, which speaks of the ultimate failure of nearly all quoted companies. This is the old ‘99% of the S&P 500 stocks contribute nothing to returns’ case. Allied to that is the Columbia (New York) mantra that some companies can beat the pack for ever, so the theory is find those “compounders” with their ‘deep moats’ and your investors will win for ever.

It was surprising how much of current fund management practice is wedded to those two assumptions. They look remarkably shaky to me, but if believed by enough of the industry, are likely to become self-fulfilling.

Which adds to another oddity: we know active managers seldom beat index investing. But this year should be showing the exact opposite. Passive long only funds are destroying wealth at a terrifying speed. So true active managers should do well too, but oddly (and absurdly) perhaps because of this “a few chosen winners” theory, they too seem to willingly forget about valuation.

True Believers

You see these few companies are (after exhaustive analysis) the nailed-on winners, so if the market halves, they will still outperform - just hold on and they will come good, the fundamental long-term analysis says so. You will recognise Cathie Wood, Scottish Mortgage are, in some measure, exponents of this too.

What is not to like? Well, self-reinforcing buying propelling valuation is dangerous; ask the Woodward investors about that one. But we also get odd clusters (identified as the winners, or the winning group, or amongst which will be winners; choose your terminology, like Tesla or Palantir or Netflix), which cut loose from sane valuations, becoming for a while mere intellectual Ponzi schemes, moving only upward, fed by endless new money.

Until they don’t.

And every time ‘buying the dip’ gets burnt, there is less fuel for the next attempt, and less appetite to try.

Too narrow a view?

I am not wholly convinced by the ‘only a few stocks matter’ theory; for a start, you have to be very lucky with your baseline, even if you can spot the gems.

But even less do I believe that you can really thread the needle to identify the great companies, and secretly buy them, without shifting their prices and then hold them, in public portfolios. If you are right (and success requires you to be right) then everyone else piles in, and valuations simply become a function of overall liquidity.

The belief that having found them, you can leave them in your portfolio for decades, feels somewhat quaint. There are some giants that do perform year on year, but we all know of plenty of giants that rise and stumble (see above), and many that have multi-year slumbers (most oil and bank stocks).

Fashion or Momentum?

So, at the conference, we had a hall of great fund managers, but also the odd IFA pleading to be told about current performance, which was simply shrugged off. Our clients are always keen to be told about our recent performance, I am sure in truth so are theirs.

Given the structure of the market, now may be the perfect time to buy Quality Growth, but that bigger question about rates and inflation trumps all. And investing, we know, is about fashion, that’s why momentum (usually) works.

I do like some of these funds, and respect their hard-working managers, but feel investing needs a hybrid approach, quality, yes, growth yes, but critically valuation and momentum too.

It seems like public policy has also increasingly drifted in the direction of this “picking winners” theory and backing what are believed to be high yield, clean, desirable industries, rather irrespective of their viability.

Public Policy implications

Once you accept fund managers can spot these, you perhaps accept governments can also nurture them and scatter tax breaks around them. This will, at the same time, destroy the rest of the commercial ecosystem, in part, oddly to fund the hoped for predictable and desirable elite. Look at what Tesla (again) has done, extensively subsidised by exchequers round the world.

Does real life work like that? I doubt it - but investing theory has clearly now tainted public policy too.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

River Deep, Mountain High

Welcome back Mr. Powell - so what is a good response to impending inflation?

After nine months or more the newly reappointed Fed Chair conceded the blindingly obvious: we have an inflation issue, along with the equally transparent need to tighten monetary conditions to quell it. At least he’s fronted up to that, unlike the position in Europe.

What diverts us is what the right response is. Some things are perhaps obvious: gold at least in sterling terms now has positive momentum again. But there is a tremendous volume of liquidity to soak up still, while stimulus will keep being pumped in for a long time. But fixed interest just looks hopeless, credit quality is plummeting, rates are rising, and returns are poor, even in high yield.

Are we clear of COVID effects?

Nor are we really clear of COVID effects. We are yet to pass beyond all the “emergency measures”. So here in the UK, VAT is still reduced, commercial evictions banned, and government departments are still showing that odd mix of budget destroying costs and below normal productivity. So, spending pressure will stay elevated for a good while. Tax rises on corporate profits and on labour through National Insurance hikes, will therefore start to bite, well before the last variant has caused another pfennigabsatze-panik. (spike/trough related panic)

Markets have also been jittery. In general, the buying opportunities just after Thanksgiving have held, which is a good sign. The subsequent gyrations have (so far) indicated a good weight of money ready to buy the dips. But there is little doubt cash is fleeing the overhyped stocks, which are far more prevalent in the US, than in the UK. The shift out of basic commodities is also apparent. So, I would still expect enormous cash balances to build up into the year end in the banking sector, albeit maybe not always in the right places. Any Santa Claus rally will be strictly retail elf driven; the old man is self-isolating this year.

Characteristics of this inflation

Our view remains that the expected high inflation is systemic, simply because of the structural damage and inefficiency inflicted by COVID. So, it maybe transient, but multi-year transient. In this case while the seasonal moves down in energy prices will be a welcome relief, assuming Northern Hemisphere temperatures stay around seasonal norms (and that’s what mid-range forecasts are indicating) - it is not a solution to the inflationary pressures.

Nor do we see the any unwinding of the inventory super cycle caused by the holiday season and the ending of lockdowns, all at once, as having much beneficial impact on price levels.

Businesses all want inventory and will keep rebuilding it across their full ranges for a while. After all, right now holding stock has little financial cost attached.

See this article published by Markit.

Most corporates are at heart squirrels; it won’t be easy to break a new habit.

So how should we play this?

The bigger issue is how to play this - the received wisdom is pile into the US, probably the NASDAQ, while having a side bet on bitcoin or some less disreputable alternatives.

That’s where most investors knowingly or otherwise have their funds.

NASDAQ may churn as dealers try to create some volatility, but the overall (and in our view inflated) levels will most likely remain.

This Omicron variant episode at least has halted the IPO madness, and the whole SPAC nonsense is washed up. Sadly, not a big surprise to see portly old London has just tried to catch a train that left the station last year.

The longer view

But it is a bubble we think - our icf economics monthly looks in more depth at how these played out the last couple of times. Not pleasant, but oddly familiar.

NASDAQ and Bitcoin may yet scale new peaks, but the river below is very deep. Perhaps that old affection for base gold is not just nostalgia?

Time for some year end reflection.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management

Thin ice skaters or savants?

Are we drifting out further from the shore of reason, confident we can slide gracefully back to safety, or do we have insight others lack? Perhaps rates just can’t rise, whatever the inflation rate? If so, they are a paper tiger. While in a week others have pondered the failure of UK investing during this century, we look at why our biggest bank seems to hate the country.

I’m talking about the economics prognostications from HSBC, our largest bank. Following an intellectually flawed change in accounting standards (yes, another one), on top of the insanity of “mark to market” comes the “predicted loan loss model”.

Now professional bankers (unlike those in fintech) don’t make loans to lose money.

So, the politicians have instead required them to assume that they do.

Do the regulators know the industry they’re regulating?

Imagine portfolio management where you assume a certain portion of your buys always fail. Might be true, but how? And if you admit you have to buy a certain number of your holdings to instantly lose money, what do your investors feel?

But although banks advance money on the basis of their credit committee assessments, the hordes of regulators deem some of it is immediately lost. Being rational people on the whole, the banks, not great fans of predicting the future (given their record), hire economists to do this for them.

Economists, as we know, actually know little, but they do build nice econometric models. The regulators, who know even less, tweak the models, the bank Boards (see above) also tweak them. Soon every model is so tweaked that the economists wonder why they bothered.

UK shown as the riskiest of places to lend

Which leads us to page 62 of the HSBC Interim Report. We read it, so you don’t have to. There on the excitingly named, but dull as ditch water section called “Risk” it is set out.

Now HSBC lends globally: Mexico, India, Vietnam, Peoples Republic of China. So, guess where “The highest degree of uncertainty in expected credit loss estimates” relates to? Apparently, the basket case to end all wicker weaving is . . . Yes, the UK.

How?

Well first up their ‘central scenario’ model sees the short-term average UK interest rates for the next five years, as 0.6%. Which at least is positive (unlike France, as they hate Macron even more), France (i.e., the Euro) rates are assumed to stay negative till after 2026.

This gloomy central scenario has a 50% chance, although for France it is a tiny bit better at 45%.

Now these are central estimates, but their “downside scenario worst case outcome” for the UK is heavily weighted, with a chunky 30% chance, and oops, France then gets a 35% chance of that disaster, neatly using up the slack just given to them, by the central scenario.

Oh, and there’s worse: house prices crater, double figure unemployment is locked in etc.

And that’s a combined 80% of outcomes sorted; for a bank, that is pretty near certain.

China compared to the UK and France

What about Mainland China, then, their biggest market, if you now include Hong Kong. Well like the US (75%), China is at a high (80%) central scenario certainty, with Hong Kong at 75%. The worst-case scenario for the PRC is ranked at just a measly 8%, the lowest of any of their major markets.

Call it impossible - a prediction that China can’t fail.

Well, if that’s what the economists believe, who are the dumb Board to argue? Well of course they can, to cover their well-appointed posteriors, they then chuck another couple of billion of extra reserves in on top of the doomsday forecasts.

So, you see the vortex, everyone, regulators, economists, non-executives are just adding to reserves, like the good old days.

Maybe they are right, but we are seeing very little sign of those incredibly low global interest rates for five years, negative in France, 0.6% in the UK, 1.1% in the US? Really? If they are right, the markets are wrong.

And it is not just technical, with a 35% chance of France hitting the worst-case scenario, no wonder the Board has shipped out their French operations to a fin tech start up, albeit one backed by private equity giants Cerberus. Not an outfit known for overpaying. With five-year rates at 1.1% the dash for cash in the US makes sense too, selling out of their retail side as well. While with a virtually nailed on, global leading, 5% five-year average GDP growth in the PRC included, surely time to expand there?

Their loan book does not bear out HSBC’s bullish estimates of Chinese infallibility

So it is with some trepidation that we look at their loan book, on Real Estate, in China. It must be massive? Certainly, markets apparently assumed so last week. But no, a paltry $6.336 billion, for HSBC that’s a rounding error. Luckily too, all rock solid, just $28m of reserves needed, although given their certainty that almost feels excessive. The Board probably slipped that bit in.

I have great admiration for HSBC, and for me personally it is a long-term hold, but I have much less regard for regulators and ‘economists’ models, about which only one thing is certain. They are wrong.

So, I try to just strip out the predicted loan loss nonsense, but it is still driving asset allocations, even when palpably false. It explains much of the last two year’s volatility in bank share prices and reported profits, it also justified the highly damaging dividend ban.

Yet the HSBC share price is still not much above 50% of its pre-COVID peak. Great investor protection that was, it hammered HMRC receipts too, for what? Based on what?

Does anyone challenge those weird scenarios internally at HSBC?

Is there really a 35% chance of France virtually collapsing in the next five years?

Or is this just part of cozying up to China? In which case as the IMF has shown, bankers accused of fiddling data for China, are not always seen as professionals and can lack credibility.

Regulators should not impose those odd fictions on real investment decisions either.

If they do real economies and yes jobs, suffer.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

EVERY DOG

Boris seems slowly to be turning into the opposition to his own party, which I suppose is not new for him. Meanwhile China also seems to be hitting an identity crisis. Neither bodes well for investors.

We apparently have a real budget due soon, but this vain Prime Minister seems bent on upstaging his own team, so we had a pile of tax rises and changes to tax law bundled out in a haphazard fashion in response to the endless (and insatiable) demands of one ministry.

A likely collision course with natural Tories

That pretty well defines bad governance, and these ad hoc excursions into major spending plans are a hallmark of waste and short termism. So, to me the investor headline should be about planning ahead for the Tory government to either fail in front of an exhausted electorate, or less plausibly given the large majority, to implode. But have no doubt that No 10 and the mass of the Tory party are now set on a collision course.

The extraordinary extravagance of the blunt furlough scheme has always been the fiscal problem, and it is hard to believe, as many bosses are clamouring for new migration to solve multiple labour problems, largely in some measure of their own making, that the government has still parked up a fair chunk of two million workers, on pretty close to full pay.

I struggle to comprehend that number in a hot summer labour market, nor do I see why employers would cling onto staff until October at which point, presumably they take a decision? Are these ghost workers? Already happily in new jobs, but having done a deal with their bosses to split the loot, their fake pay for not being? Are these people HR have forgotten or are too scared to fire? Will they really try to pick up work they put down eighteen months back, in a largely different world and probably for a now quite alien organisation?

Who knows, but the whole thing cost £67 billion (so far) and that’s what Boris needs back. I challenge anyone to give a lucid explanation of how his latest proposal “fixes” social care for the elderly. Nor to explain how in parts of the country like this, with no state care home provision anyway, it can ever be called “fair”. So, to me, it is just bunce for the ever-gaping maw of the state, and the idea, with Boris in charge, that it will ever be temporary or even accounted for, is somewhat risible.

What would “fix” social care is transparent, autonomous, local provision, not bullied by a dozen state agencies, not run by money grubbing doctors, not harried by property developers and absurd land costs, nor daft HMRC grabs on stand-by staff pay, and it needs to be highly invested in simple technology, all IT integrated with the NHS; not this crippled, secretive, subscale mess.

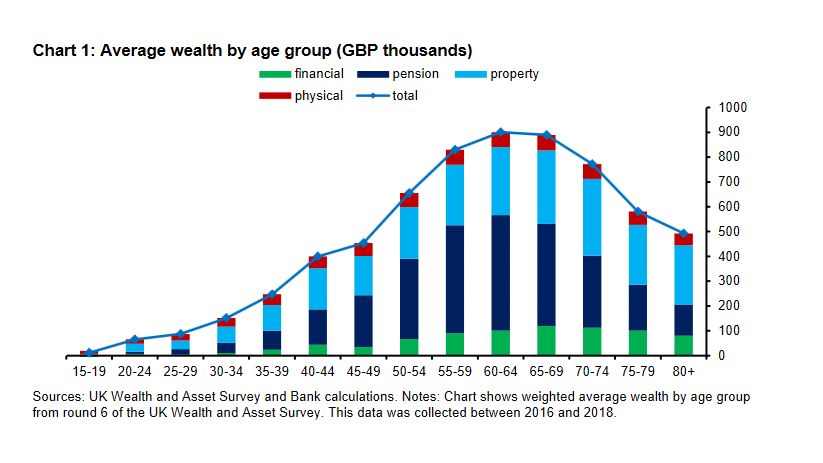

It is not that there is no problem, but it is as much operational as financial. A recent Bank of England paper looking at wealth distribution highlights how in retirement property comes to both dominate assets and also shrinks far more slowly with age.

(Sourced from this speech given at the London School of Economics, by Gertjan Vlieghe, member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.)

Of course, the crux here is seeing a family home as both an asset and an essential for life. That is the distortion, and this fiddling with care rules attacks the symptom, not the cause.

Can you trust a word he says?

So, now tax on income rises, a broken promise, employer tax rises, broken promise, the ‘triple lock’ on pensions is ditched, broken promise, and to top it off those working beyond normal retirement age (now 66) get a 25% tax penalty, via another broken promise. Oh, and if you are mug enough to save, then dividends will get hit too.

Again, there is a real problem but this is by no means a logical answer either: I guess the Treasury were applying heat on excess debt, and this is sand kicked back in their face, but it shows no sign of anyone solving anything. The UK has both high debt levels and no supportive currency block around it, sure France and Italy look bad, but they have Germany to help. The UK does not. Hence the anxiety.

So, Boris has had a fine Cameron-like bonfire of dozens of electoral promises; the worm turned on Cameron (and Clegg) when he couldn’t keep his word, and so it will turn on Boris. This time he won’t have Corbyn as the pantomime bete noir to bail him out. Indeed, Kier Starmer’s response linking this problem to inflated property prices is remarkably prescient, even if his typically confiscational solution is not.

These tax levels (as a % of GDP) have not been seen in fifty years, for an economy with a noticeably less effective grasp on government expenditure and a rather less globally competitive commercial base.

While tax rises are emerging everywhere (see below), and public service reform has become a simple money equation, need more service, spend more money, a dangerous one-way road.

Source: from this primary report

While notably, ‘buy to let’ is again left untouched. London house prices have doubled in this century, the FTSE 100 has moved from circa 6800 at its late 1999 peak to 7030 now and remains below pre-pandemic levels. So clearly this is not the time to hit the investors in jobs and business, who have had a 5% nominal gain (that is a 60% real loss) in twenty years and yet to leave the buy to let rentiers trading in second-hand hopes, with their 60% real gain in that time, untouched.

And don’t give us the dividends argument; the buy to let plutocrats get plenty of rent and all their sticky little service charges. This measure simply hits the workers and investors in business and pampers the bureaucrats and the rentiers. It makes very little sense, unless you are a senior civil servant or a retired prime minister, like Blair, of course.

Chinese insularity - the new version

Meanwhile China I feel is now detaching itself from both the rule of international law (in so far as it ever bothered) and more interestingly the world financial system. It may indeed end up better off, but for now (and this is also a change from much of the last 50 years) it does not feel it needs to attract external capital.

So much of its trade and capital markets engagement has been predicated on securing capital; this is an odd and novel twist. Although perhaps a logical response to the West, who rather than conserving capital as a scare resource, are immersing the world in torrents of surplus cash and inflation.

Much of China’s policy about their own global investment (so outside China) also used to have the same theme, driven by the desire for returns, influence and to hold their own export-based currency down.

But no more, it seems, and their inherent desire for autarchy, the hermit kingdom trope, has only been emphasized by Trump, WHO and the madness of the internet. It apparently wants to be the new Germany, (no longer the new USA), so it will be insular and conservative: cautious, not driven mad by debt and the baubles it procures.

Well, if true it will be different, whether it can really be done, without a wave of disruptive defaults is unclear, but don’t doubt the length of vision, so unlike our own government. While a theme of this century has also been where China leads, the rest must reluctantly follow.

Even a dog has its day, but for investors both the UK and China now feel significantly more canine than at the start of the summer.