We take a look at three things that move markets: macro, politics, and mood.

We have an inexplicable market rally to explain. On bonds we remain wary and we also take a look at the Keynesian attitude to inflation.

The obvious explanation for the market rally is Santa Claus, or perhaps in more mundane terms mood. The markets (in both bonds and equities) have had a beating, the shorts were satiated, the cash piles vast, and markets had simply had enough.

So, back up like a bungee it went, the heaviest fallers often bouncing back the highest.

Inflation (still)

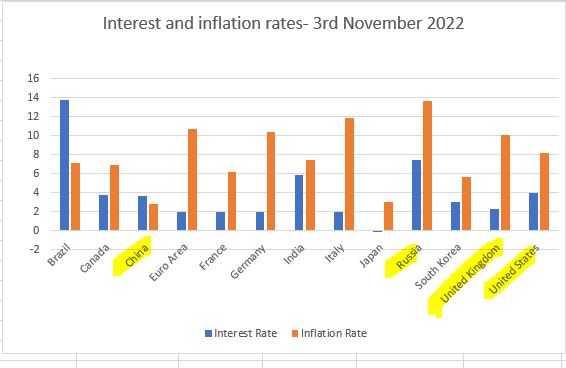

We can talk endlessly about peaks and plateaus for interest rates, but we still don’t see any measures likely to get inflation back to 2%, for several years. But it seems that doesn’t matter now. The so-called base effects, the softness in commodity prices, the excess inventory (rather than prior shortages) all mean inflation will fall, and for most, for now, that’s enough. Regardless of how far or how long it takes.

Indeed, there is some realisation that if prices are really rising at 10%, it is best to buy now, not wait for higher prices.

And for a lot of service-based firms, capacity is indeed short, and they feel free to ram through price rises, to open up their gross margins, assuming (rightly) that if everyone else is doing it, and no one really knows their true cost bases, they are winners. As they are.

And as we long predicted, the elimination of competitors, and monetary tightening, leaves big firms free to expand into a void. After all they have faced flat prices for a long time, so the chance to move prices up is most welcome.

Seeing it like Keynes

So, it is perhaps useful to remind ourselves of the Keynesian view that inflation is “a method of taxation” which is used by the Government to “secure the command over real resources” in the same way as ordinary taxation. So, he was really not a fan.

How then do we explain the UK Treasury (all notional Keynesians) using abundant deficit financing to sustain already overheated demand?

Well in short, we don’t, it is just politics. By raising pensions and welfare in line with inflation, the UK Government is acting as if they need to secure the economy against high unemployment and a recession. The classic ills Keynes addressed.

Although (so far) neither of those disasters is evident anywhere, except in their own predictions. Older hires are rising which is generally a sign of overheated labour markets, looking for marginal supply.

Which is quite neat, as if those evils don’t arrive, the policy clearly worked and if they do, well our politicians tried their best. Given the shambolic recent failures of Treasury predictions, that they have any ongoing credibility is really quite remarkable.

But that process also embeds the long desired extra taxation, resulting from the inflation they are not quelling. There being no limit to how much Governments want to spend, there is equally no limit to their appetite for tax.

All of which nicely pings the pinball back to the Bank of England, which was so very unhelpful in the early autumn, so let’s see how they do now? Will they truly show the steel of the Americans or the Micawberism of the Europeans?

And interest rates (still)

The interest rate (beyond the short-term market rally) is therefore still the big decision. If inflation is here to stay, it all depends (once more) on the US, and on what reason the Federal Reserve has to stop tightening, even with high inflation. We can’t see one. Albeit we are very reluctant to guess there is none, with such strong markets. And it maybe they just had an arbitrary target, which they have now reached.

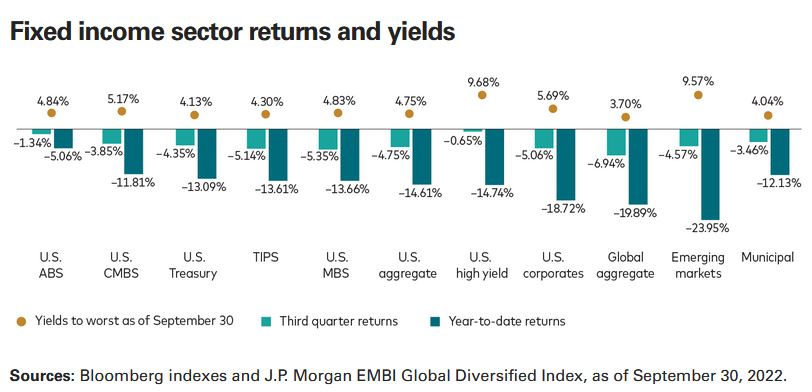

From this page on the Vanguard website

However, that gives us a trio of reasons (apart from the rogues’ gallery above) to still avoid bonds.

- If inflation stays elevated, bonds are a rip off, as they have a negative real return.

- If the Fed stays strong, bonds are a rip off, because base rates are still rising.

- And if the Fed wins, but others fail, then bonds are a rip off, because the dollar keeps rising (and hence other currencies fall).

In summary the only bonds that look attractive to us are still short-dated US ones. Which is not really new, nor does it make long term sense, with strongly negative real rates still. Bonds by definition can only have a real return when rates exceed inflation, either due to falling inflation or rising rates. And we don’t see that crossover for a while.

A THREE-LEGGED STOOL

So, we return to that trio: macro, politics, mood. Political uncertainty is much lower (for the next two years) in both the UK and US, and perhaps is not that unstable in Europe either, although the Ukraine war could still change that significantly.

Even China seems a little less keen on confrontation.

Macroeconomic factors really do not yet feel encouraging. It is way too early to declare victory over inflation.

Paradoxically when inflation is clearly beaten, earnings declines will then set in, as pricing power recedes. The failure to see that decline, will indicate inflation remains a threat.

And finally, mood – yes, the mood feels good, for now, although how long that remains is as much psychology as anything else. But if bonds do start to slip, don’t expect the party to keep going for long. Nor will recent dollar weakness persist.

The overall view seems to be that the handbrake turn has been completed, we may slide a bit more, but we won’t spin again.

But that assumes we know a lot about the track and conditions – do we?