PICTURES OF MATCHSTICK MEN

I noted at the end of our last bulletin, that markets are feeling strangely bullish, for a few reasons, which I share. Although only in some places. I still find little attractive in most debt markets. They are cheap, but given losses this year, are they good value?

And UK politics is becoming boring, which is no bad thing.

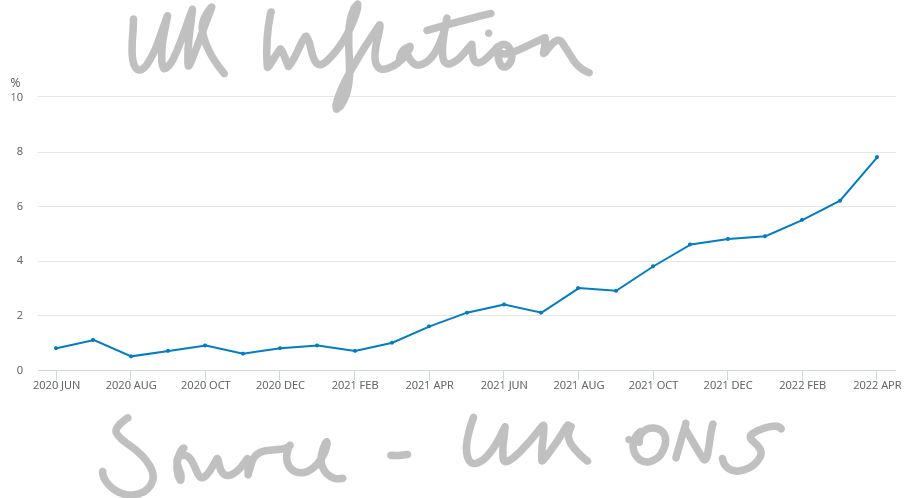

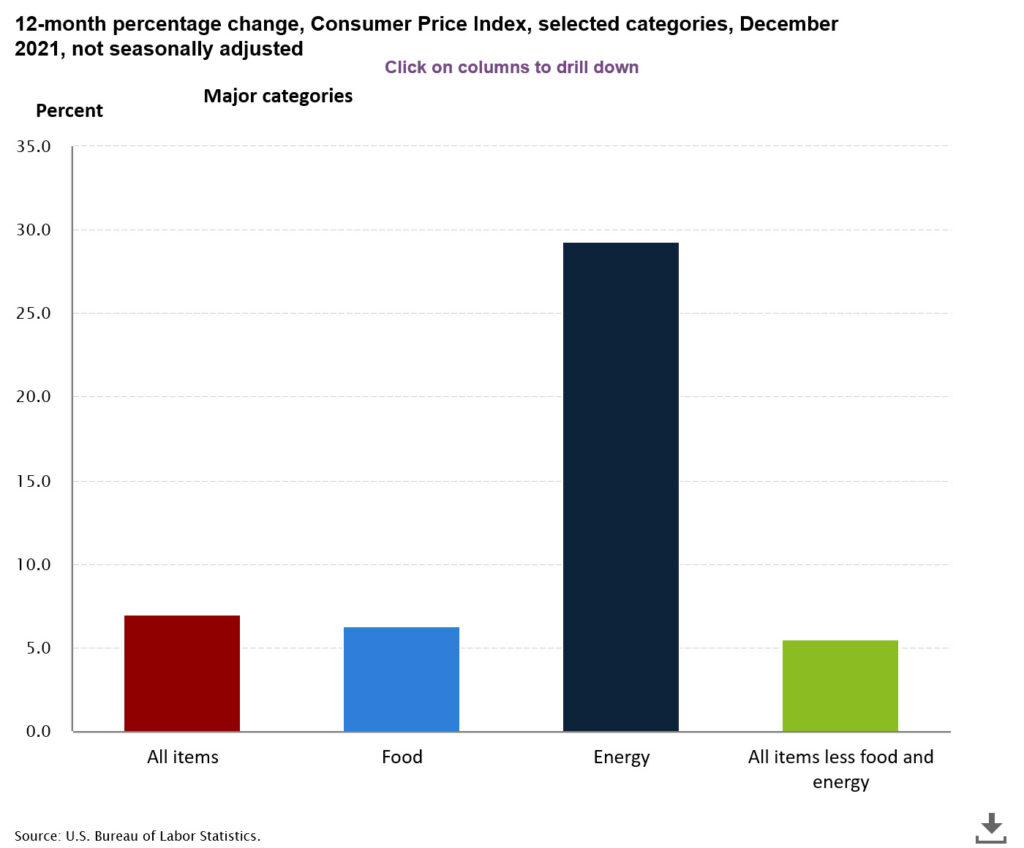

So, were we right to predict that interest rates alone cannot tame inflation?

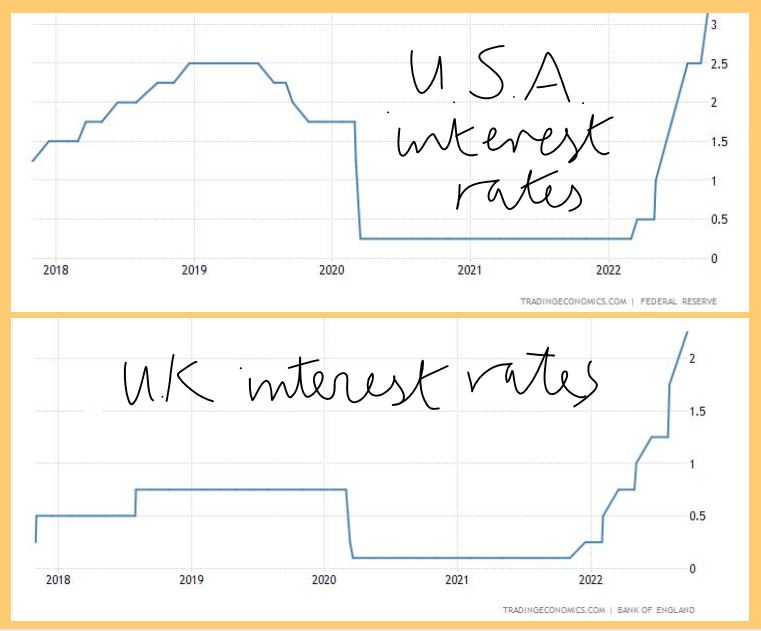

Our original thesis for this year, that interest rates could not tame inflation alone, maybe is right. The level needed would cause too much damage. But that is applicable (we now see) to the UK, but not as yet to the US. And oddly perhaps not as yet to the EU either, although Lagarde midweek, perhaps had the same tilt. But German profligacy may wreck that.

The logic is the same for them all. You can’t tame this beast by rate rises alone, as double figure inflation needs double figure interest rates and that is just not happening.

The UK is certainly not prepared for that level of rates and fiscal restraint is therefore now required. Fiscal drag will do some of the heavy lifting, and energy price declines a fair bit more.

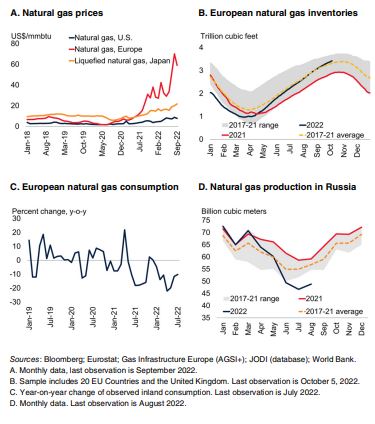

Some commodity market statistics were released by the World Bank, this quarter. The above graph is extracted from their statistical report

But tax rises and government spending cuts will still be needed to cool the UK labour market. In particular the public sector must be reined in, or service cuts made.

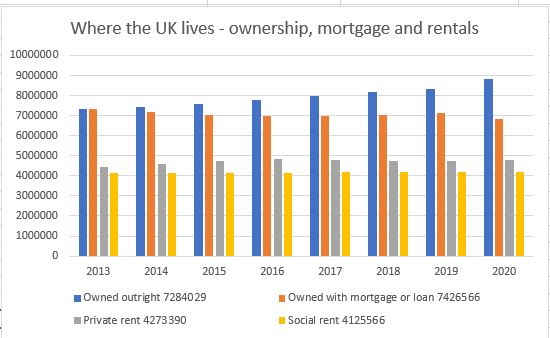

Earnings will fall, taxes rise, growth stall, discontent rise. But still no collapse in housing (secondary) markets or in employment.

Nor do I therefore see much rise in loan defaults. This makes the recent round of forward-looking bank provisions unusually daft. You can’t audit the future, so how can you include it in historic accounts? A weird hybrid. Best to ignore all that and focus on now, and now is still not terrible. With a pretty hefty valuation discount in situ.

(Data downloaded from the Office of National Statistics for this in house graph).

The US political situation

In the US, The Federal Reserve have effectively said if there is no fiscal restraint, they will ramp up rates till there is, or inflation falls. That is scary, but it looks as if the Mid Terms will hobble Biden and stop some of his fiscally reckless measures. He thought the wave that toppled Kwasi missed him, but it was the same ocean, and likely will give him a rough ride too.

Biden’s approach felt good, overindulgence often does, but the pain of the untethered dollar is now starting to hurt US earnings, and in time US jobs, however much they dream of legislating against that. The impact of rate rises is also probably less than it sounds in the media, partly because most reporters are likely to have mortgages, whereas a growing number of investors don’t.

Overall US government policy remains to force up inflation and challenge the Fed to sort it out. Hence all the Fed threats are directed not at the market (which cares) but at The White House (that does not). Mid Terms (on the current path) will therefore be a big boost to US markets, as it means Congress at least, will start to work with, not against the Fed. As with Kwasi, a reckless budget will not pass unchallenged again this time. Those extremes belong to the COVID era, that is now over.

Comparison with the UK position – and where Europe maybe is headed

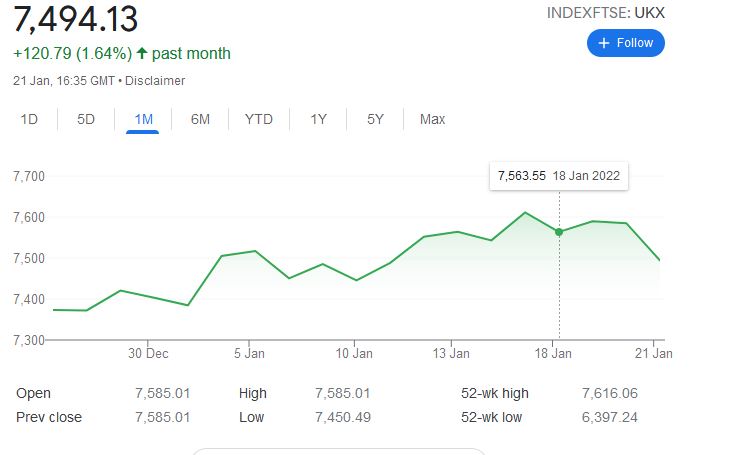

With that battle already won in the UK, both sterling and to a degree UK rates are reverting to the status quo ante. And as sterling rises so the FTSE falls; that link also remains. If the UK is neither chasing interest rates up, nor letting the pound fall, it gives Europe some cover to do likewise.

In truth although sounding dramatic, in the real world it is inflation that really counts not (as yet) interest rates which are still absurdly low.

The Tory Party – what can we discern?

Talking of status quo, that’s where the Tory party is now headed. Cameron drifted too far left, Boris dithered, Truss drifted right, and now the new government is a hybrid, although colloquial English perhaps has a stronger word for it.

I sense that spending decisions may correctly be back with a powerful Chancellor. There is a seeming party truce till the next election, when half the current Cabinet seats will vanish anyway, and then who knows?

Or if this coup and enforced hybridisation fails, we really will know the party is split, and a General Election could follow. Unlikely, though.

Why bullish then?

US earnings except for highly indebted outfits, will probably stay surprisingly strong for a while yet. And likewise, the dollar pivot point is being pushed further out, as no one else in the developed world is going for rates quite that high (or that fast).

There are also two market forces to look out for, rising rates and slowing growth is one, but the simultaneous loss of liquidity is another. The former will cause a patchwork of changes, both good and bad, but the latter the ending of a multi-year bubble.

It all remains cyclical – a transition, not a bounce

The difference is key, rates are possibly a two-year cycle, a bubble a ten-year one. The bubble in non-revenue companies, and in absurd multiples for even profitable tech, will take longer to deflate, be slower to re-inflate and be muddied further by all that spare capital accelerating technological change. This is still not an area we either feel confident in, or trust their valuations.

If we really are back to the status quo in the UK, about to be in the US, why would markets be going down, down, deeper and down?

Lend me your fears

I come not to praise Kwasi, but to bury him. This is an explainable, predictable but probably futile coup in the UK Tory Party, along with more King Canute from Bailey of the Bank.

But in markets there is abundant good value, but with few clues on how, or at what cost, inflation is to be tamed. Or indeed what may escape this time.

Political Manoeuvres

We have long noticed the Tory party’s splits and factions, broadly between the left and the right wing. This was a chasm Boris was uniquely able to bridge, by talking right, and acting left. The puzzle, as we noted, was why the left would bring him down to replace him with a right talking right acting Prime Minister. The preference was for a Blairite Conservative, low tax, high spending, but a steady reformer, with a lethal penchant for foreign wars and illogical hatred of the Euro. After Kwarteng’s departure, the Tories now have the doomed high tax big state faction back in charge again.

Hence the need for a pretext to overrule the party members and threaten Truss with the ever-gleaming sword of Damocles, held by the 1922 committee - we are back where the plotters wanted to be after Cameron – with the neutral Hunt playing the safe stooge to hold the fort.

Unlikely to win the next election

It foretells the inevitable party split – but we had never seen another Tory term as possible, regardless of the leader. Nor have we ever seen Keir Starmer as needing to do anything but sit tight and keep a grip on his party. If he is also spared the crippling cost of a really tight General Election, he can now face down the Trade Union money men as well.

As for Kwasi, if he stays the course, his troops will yet triumph at Philippi, he is by far the best the Tories have just now and looks to be the future. He has understood that if you fail to free the supply side, in a new productivity revolution, the current national decay will just go on, as it has for twenty years or more. But he has also not torched his future, Miliband style, in the wrong leadership move.

Will any of this stem the attacks by market traders? I doubt it. Will any of this forestall the inevitable sharp rise in interest rates, I doubt it. Or indeed stop ongoing sterling losses. To quell inflation requires interest rates above inflation, you can’t bear down from below. It remains daft to think UK interest rates can be effective whilst remaining underneath US ones either, as we said in our previous post.

Both clipped from this site, and set out side by side. The core data as is cited below are from the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England respectively.

So, what is the shape of this next recession?

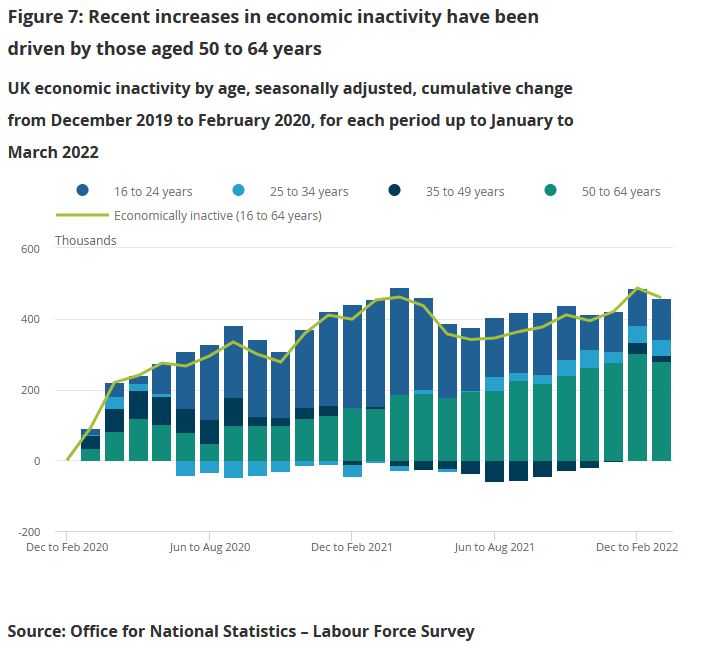

I think we are now starting to see it. Not that much unemployment, the current tight labour market, without addressing increased workforce participation, is going nowhere. Nor is a secondary residential property crash certain. That is so last century, both areas are now far more heavily fortified sectors than they were last time. And both are now designed (and legislated) to be fiercely inflexible downwards. That is what the current labour market (and our dire productivity performance) is telling us.

House prices are propped up by a very generous market backdrop, ongoing vice like planning, high land taxation, tons of liquidity and a deep political fear of the consequences of a collapse. For all the moaning, borrowers are still able to load up at negative real rates, with a highly competitive mortgage market and generous fixed term offers.

But do expect a general slaughter of small businesses (or rather the current collapse will go on despite the various support packages). Expect weak margins for UK based firms, ever more exposed to competition, from far more generous and protectionist states.

WTO rules really are in tatters now and routinely ignored by powerful countries like the US and Germany. Expect a resulting fall in quality both in goods and services, again a continuation of current trends, as globalisation retreats.

But remember too, that so far, we do have inflation, but not a recession. The current dislocation is caused by a resource switch towards savers, who at all levels have had slim returns for a while, and we will now instead punish borrowers, who have had an absurdly easy, subsidised, inflationary decade.

The big picture, overall

Meanwhile in the energy world, a resource transfer is taking place from energy users to energy producers, who have likewise had a thin time of it. That those energy producers are places like the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Nigeria, Brazil, is a remarkable own goal for Europe.

But it is neutral for the world.

Indeed, much of those surplus funds will now be collected as various direct and indirect tax revenues, or to pay down debt, or as new investable funds, or distributed as dividend payments, but very little of that vast energy price transfer leaves the known universe.

For Europe, however the decline happens with the slow loss of productivity, plus the demographic torque. Meanwhile borrowing our way out, is suddenly becoming far more painful.

The political turmoil is ultimately from this change, and the longer states borrow more and pretend nothing has changed, the less effective will be their remedies. And indeed, the more the big efficient producers, like China, the US and Saudi Arabia will thrive. Neither more debt, nor protectionism will solve this, nor indeed will more global military adventurism.

Confidence is understandably damaged

Given that backdrop the mood music is damaged just now. Markets are trying to spark rallies, but with no real confidence yet.

Investors sense there is value, but with too little data to know where.

But whisper it quietly, Santa Claus is due, and the market mood is not quite as bleak as events suggest it should be.

Seeking an end to the turmoil

This market turmoil feels interminable, as asset markets stumble to find a firm footing and churn relentlessly. Instinct says that’s a time to buy. But there is so much happening, as this multi-year trauma unwinds, it is quite hard to know what.

Although we try to segment it, the key problem is the terrible dishonesty of politicians, who have bullied their citizens into an unthinking reliance on institutionalised theft on a grand scale and a belief that nothing really matters, as long as you have a press release to deflect it.

IT IS ALL STILL COVID

So, working through piles of annual accounts, as a pleasant distraction, (I have always enjoyed history), the one repeated theme, is of shrinkage, under investment, caution. This, in a way, is natural because COVID reset two years of global production, and indeed destroyed large areas of output and services. Which also makes it terribly hard to understand what “normal” is now.

Not helped by the piteous vagaries of those craving spurious accuracy. Big banks and resource companies seem overall just to want to carry on shrinking, which is odd as their results seem very good. But they are not. All that has happened is they took big write offs and reserves in 2020 (which were not needed) and that then reversed in 2021. However, the underlying business volumes fell, the trend to more disposals than acquisitions was unremitting; these are shrinking businesses.

To the populists who believe higher taxation lowers inflation (are they mad?) and indeed, to market commentators, this looks good, but it is really not, productive employment is shrinking too, workforce participation is not roaring back.

And with inflation we will again see plenty of “top line beats” or rising revenue, but that too is an illusion. And indeed, raised dividends. For example, Shell now proudly offers a 4% dividend rise, as if that is generous; last decade it was, but not now.

That is now a real dividend cut.

As we struggle with a badly damaged global economy, government policy is unremittingly wrong-headed: you wonder what we could do worse than the vast debt fuelled bubble after COVID?

But then we stumble on the idea of doubling or trebling domestic fuel prices. We do this to punish big energy exporters like Saudi Arabia and Russia. Only a simple clown could believe that will help us, and only a child-like vandal, that it will halt Russian armies. We take our own possessions out and smash them on the street, like voodoo dolls, because we are hurting and want others to hurt too. Nuts - it is tearing our own clothes in blind anger, but we ourselves are not the enemy.

Meanwhile, underneath all this noise, is the game up?

Is the expansion we have seen for two decades based on cheap Asian product imports, and low interest rates fuelling inflation in non-traded goods now done? The non-traded category is everything that can’t be shipped in. Land, services and the like that must be consumed, where they are provided. Although with that went quite a lot of imported labour consumption too, of course.

I keep wanting to write positively on China, but I simply don’t know. Is their COVID winter politically sustainable? Is it a massive pivot back to a closed state? Was the aberration their great expansion, and they are now reverting to being a hermit kingdom? Instinct again says no, who would reverse the greatest success story of our time? But evidence the other way just slowly piles up. Another giant nation seems slowly to be sliding towards belligerent stagnation.

And so much went crazy with the toxic mix of low interest rates, and excess liquidity. We may at last have learnt that if you have a blocked pipe, spraying it with gold is not a remedy. The pipe stays blocked, but everyone gets flecks of gold on them. Better (and cheaper) to hire a plumber.

WHAT WILL BE THE THIRD POLICY ERROR?

We certainly don’t see the recent bubble implosion reversing, for all the bluster, crypto, and concept stocks, feel to us like a long term drag on the indices, remorsesly lower.

The turn feels to be more likely in bonds. The fight is between a shrinking set of outputs, but rising prices and apparently rising consumption. As long as policy blunders persist, and they show no sign of ending; then the upward pressure on rates will also persist.

But we doubt that any conceivable interest rate rise can solve this inflation. In short, the fire must burn itself out or at least no longer be stoked up.

In which case posturing about a long run 2% 3%, or 5% rate is really guesswork. But that’s the big question. If it is 3%, we are already there, but there is no great market conviction on that. At least the belated but long inevitable addition of the Europeans to rate rises, should take some heat off exchange rates.

LETTERS I’VE WRITTEN

What about Boris? I was quite surprised at the swift and co-ordinated move to a no confidence vote. The Tory party is rubbish at a lot, but plotting it does do rather well. And also surprised at the vote itself. The rebels can not win, without a candidate that both factions like, that is the real Tory party and this odd “Cameron light” lot in Downing Street. Of course, Boris himself is already largely that candidate, talks right, acts left. Which means all sides hate him, but neither can replace him, for fear of the ‘wrong type’ of fake instead. Just what you want to be, you will be in the end.

There was also a fair bit of bile, stirred up by the media, and rather infecting what are loosely called the “activists”, who are anything but, but do bend their MP’s ears. They just want to dislike Boris and his lack of scruples, but also like the gifts he brings them.

They don’t want local trouble, so enough of those MPs voted against him, to keep their local associations happy. If that “terrible man” stays in office, they can at least claim they did their bit, but ‘others’ then let the side down.

Will Boris last up to the election?

Our core belief remains Boris stays in power long enough to hand over to Keir and Nicola. But perhaps we have rather less conviction than last week. We thought Keir was more likely to be in trouble, but perhaps the Tory plotters could be desperate enough to finally agree on a candidate? Either way this is now a lame duck UK government.

But then like markets, outside events may rescue it, it’s just we really can’t see how at present.

As for where to consider investing? Our MonograM momentum model loves the dollar, for sterling investors and for USD ones, increasingly just cash, and decreasingly the S&P, so long the global refuge.

But that is in no way a recommendation, just an observation; more detail on our performance page.

He who pays the piper

A very strange quarter: the FTSE100 was up, in sterling terms the S&P 500 was up, and the Russian Rouble ended where it was just before the Russian invasion. Short term dollar interest rates are nicely positive at last.

So where is the problem?

UK policy changes – could we finally be leading in economic policy?

Well, at long last the UK Chancellor has finally realised that just throwing money at inflation has one clear outcome: more inflation. This is tough lesson learnt back in the 1970’s and seemingly since forgotten.

If true it is a turning point and we predicted that it must always come sooner for the UK, if it persists in staying out of the Euro, than for bulkier continental currencies. Sunak also seems miraculously to be finally tackling some long overdue, multi-parliament, structural taxation issues, a rare sign of political maturity.

Whether he can hold the line against an increasingly dimwitted set of MPs and a media who constantly bay for more fuel to be added to the inflationary fire is unclear, but at least he has had the courage to step out into the unknown night, not cower by his warming bonfire of magic myths.

Nor is it clear whether he has the clout to unpick the cosy mess created by Theresa May and her childlike energy price fixing, or the ensuing nonsense from Ofgen. This fine-tuned capacity to the point of absurdity, guaranteeing a massive breakdown in the generating buffers, which had been painstakingly installed under a series of Labour governments.

Inflation policy is being taken seriously

But Rishi is trying; to cool inflation you simply must have demand destruction, there is no choice. This type of deep-seated widespread inflation will be hard to quell in any other way. True, areas of it can be contained, but it is hard to hold it all.

He is lucky to be helped by a Bank of England that seems to be serious about its brief, not regard it like Lagarde and Powell, as some kind of political inconvenience, to be wished away in double talk and evasion.

But he’s unlucky in other ways; we noted a while back that China no longer seemed to care about headlong export led growth, or more broadly about access to hard currency. It feels it can invest with and gain from its own currency and avoid importing the monetary excesses of the West. That in turn means it cares less about the endless flows of cheap goods to Europe and the US, and conversely about soaking up those surpluses in luxury goods and services. None of this is good for our inflation.

Meanwhile by eliminating the oddly divergent starting points for the two income taxes, National Insurance and Income Tax, Sunak has opened the way to many benefits. It continues to drop taxpayers out of the system, despite desperate measures by HMRC to suck more in. A key step, and a sign of, for once, a more liberal, more efficient government. Many more steps are needed to unshackle wealth creation, but it is a start. It makes much of the Universal Credit complexity around thresholds also fall away. Most of all it is a step closer to combining the two income taxes.

Politically this is highly desirable, as it strips away the pretence of a low starting rate of taxes on income.

It perhaps even gives an excuse for the otherwise inexplicable step of introducing National Insurance on employees passed retirement age. Given so much of current inflation is due to the mass withdrawal of older workers, another step in that direction looks remarkably stupid, but perhaps it has a higher purpose. It is good to see that the “Amazon” tax as Business Rates should be called, as it gives Amazon such a massive earnings boost, is also clearly still under long term review.

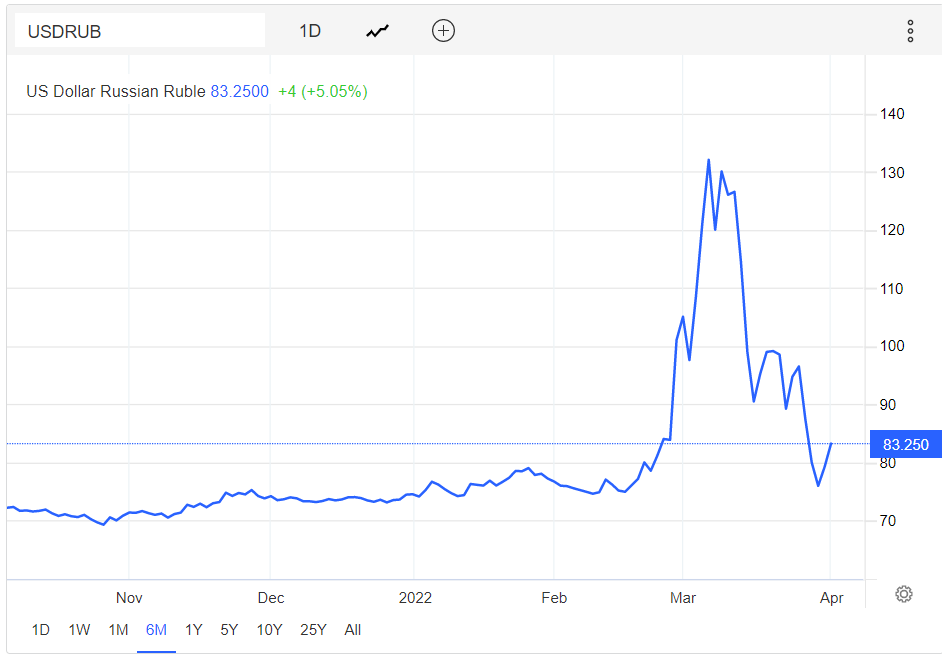

Why has the rouble recovered?

Source : this page on tradingeconomics.

The recovery of the rouble is of course not a market step alone, doubling interest rates, exchange controls and the mass withdrawal of exports to Russia from the West, are part of the story too. But it also shows a turning point. At first the West was so shaken by Russian military attacks, it was prepared to follow its own scorched earth policy, regardless of the harm caused to our own people and employers.

But at some point, the realisation that Ukraine’s army would hold, that Putin’s army was not that good after all, especially up against modern weapons and we start to understand that the further blowing up of our own bridges just raised the ultimate bill. Here are the sanctions we've imposed.

So, it seems it is no longer true that any price is worth paying to help Ukraine or hinder Russia. Clearly, we don’t have to jettison all our principles in dealing with other tyrants, nor one hopes do we need to alienate every piece of remaining goodwill with the rest of the world, by panicked grandstanding.

The mob is still rampant, goaded by an American president for whom no European economic sacrifice is too great.

But maybe it is also time to tell Ukraine that no NATO also means no imminent EU: Brussels has its hands full with its own struggling ex-Soviet states.

And what about Powell and his policy?

Well, we don’t expect him to hold inflation down with his trivial rate rises, nor politically can he do more than tinker. It seems too that Lagarde at the very least has to get Macron back in, before telling the bitter truth about rates.

So, we feel the bond market has rates where the market would like them to be, in the US, not where they will be set by the Fed anytime soon. And the Euro is now in a very odd place, still with monetary stimulus being applied and with an unstable gap to US interest rates.

So, we may look to be where we were late last year, but in most cases the cracks are now alarmingly wide.

Europe, quite urgently, but the US as well needs a sharp jolt upwards in rates to halt inflation.

Oddly only the UK looks to have spotted the danger, stopped the false COVID ‘economic expansion’, tightened fiscal policy, reformed taxes and raised base rates steadily, towards where they need to be. How unusual.

Long may PartyGate continue if this is the end result.

We will take a break for Easter now, and resume on the 23rd.

If the first quarter is a guide, by then everything will have changed again.

Sea change

A trio of influential knaves to worry about this week, united by a belief that “this time is different”. Well pantomime season is behind us, however we can still all shout “oh no it isn’t”.

Boris seems to be the least of our problems, if the greatest of villains, for the scurrilous crime of enjoying himself, what a rat. While Powell is providing an increasing threat to the poor and exploited across the globe by generating financial instability, and the lamest of the lot, Lagarde is just repeating a political line. The Euro zone debt figures look like this. A sharp rise from an already overstretched position, but still benefiting from falling rates, so when that rate line turns, the problem will really bite.

Will markets ever trust the Fed (if they did this time, outside the gilded denizens of Wall Street) again? Hopefully not, the trouble with putting administrators in charge of Central Banks is they rely only on historic facts, it is in the job description, that’s what they polish, hone and serve up.

But the economy is dynamic

The mismatch is that the economy is dynamic, and has no printed rule book, beyond that of the rocket; what goes up, must come down, immutable like gravity. And you simply can’t wish gravity away.

So, this Fed is programmed to repeat what it can see looking backwards, and all the obedient commentators on Wall Street who simply echo its nonsense, are of little use, except to fleece the gullible and to signal false comfort to one another.

Having said for most of last year “there is no inflation” they have turned on a sixpence, to say inflation is now out of control. Talking of six or seven rate hikes; they wish, just banker’s fantasies. Although markets, not surprisingly, are now suddenly jittery.

Investment implications

This week we went from feeling over 20% cash was too cautious, to feeling we had missed the boat on value stocks, back to feeling 20% cash was really just fine, all in the space of four short days.

So, because that sea change in inflation expectations was so abrupt, this is a genuine dislocation, we do see the NASDAQ and both the concept stocks on infinite multiples and the mega tech stocks on thirty- or forty-times earnings, as in some trouble, in a process that does not feel over yet.

There is a ton of selling, and the spoofing assets, including crypto, will be heading down, in a dip that feels likely to be around for a little while. But two things stand out, firstly until rates start to top out, this excess money simply can’t go into bonds, so what happens to it? Secondly if the market assumptions about Powell and Lagarde are both right, you are going to be paid handsomely to hold dollars, while simultaneously being charged to hold Euros. We don’t see that as sustainable either. One must be wrong.

Looking ahead

This is why Lagarde’s confidence in no rate hikes, feels like a lawyer’s bluff, as if currencies move, it won’t be her choice for long. While uninvested money, on which fund management fees are still charged, always makes asset gatherers nervous; it will all go somewhere.

That also leaves the question of how much growth we will actually see, as if it is below expectations, then inflation will be choked off, labour force participation will fall, US rate rises will run out of steam. There are already signs of that. While given the scale of market movements, the ending of bond buying by the Fed (long overdue) and even a modest run off of the balance sheet, will be pretty irrelevant, both are really drops in the financial ocean.

The froth blown off

So, the good news is we will see normal investment conditions, the froth blown off, bonds producing a yield, along with slower growth and moderating inflation, which we do feel will be backing off by mid-year. All of course will rather depend on the progress of COVID, because we still see (and have done for nigh on two years) this inflation is directly caused by COVID responses.

Reducing the output capacity of the economy, with no cut in demand, has to cause price rises. These price rises will exist everywhere COVID does, so trying to pin them to a single cause or location is not easy. They will persist until the demand/capacity equations correct, which with COVID is a multi-year task.

The FTSE finally gets a look in

So, a sea change yes, a market dislocation yes, but if it is as bad as is currently feared, with some big winners resulting in the financials, real assets and energy. All of which, on those fundamentals, still look to us good value, hence the visible support for the FTSE 100.

While if it is not that bad, sufficient money will flow into US Treasury stock, from low interest areas, forcing the dollar to rise, and rates down, until other areas are simply pulled along. So no, we won’t then be getting seven rises on this data and equity markets can start to relax.

And what of Boris?

Finally, Boris, now degenerating into farce, but much as we hate what he has become, we recognize one wing of the Tory party feels he is too right wing, while another feels he is too left wing. Both dream of replacing him with their own, but in so far as he splits the difference, the risk that the other faction wins, should keep him in office.

Either faction will demand more of his replacement than they can ever deliver, given that core fundamental split, so such a divide simply hands Downing Street to Keir Starmer. For now, I still feel he survives, and given his nature he will remain impervious to change, but remarkably adept at promising it.

Sterling seems notably unfazed by it all.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Limited