Stop Making Sense

The benign Powell’s fireside chat has left us all very happy, while I have been pondering the Yanis Varoufakis saga from afar. So how did Greece survive the doom and gloom after the Euro crisis?

An apposite topic, as high state debt, unproductive spending, and uncertain or burdensome credit, pretty much all over the West, apparently beckons once more.

The Song of Chairman Powell

We start with Chairman Powell in his recent Q&A: he could hardly have been nicer, the equity markets loved him, the bond markets sweetly retreated, and the dollar fell away.

It was not so much the repetition of ‘data dependent’, a seemingly meaningless phrase, or the deft swerves around repeated questions about the path of rates.

It was more the extra lengths he went to, to dismiss the data outliers, particularly on much faster GDP growth (4.9%) in the US economy, for Q3 and the sharp upward shift in longer term inflation expectations. The bond markets had found both metrics spooky.

The GDP number was dismissed, rather airily, as related to strong consumption, which in turn was linked to high employment and rising real wages on the one side, but more importantly to COVID savings balances. Although he admitted no one really knew what these were, but somehow, they were still contributing.

The inflation expectations got dissed even faster: Powell thought it an outlier, more recent data was far more consistent. Suddenly the evil portents were gone.

It would be wrong to think he knows what he is talking about (why start now?) but right, to know how he is feeling; that’s it. Sure, he keeps the rate rise out in the open, like an old dog, but the chain is lax and rusted, the beast benign.

It would take a lot to make the US raise rates again and he was happy with tighter monetary policies. Even nicer for the long end, while Powell is not sure where the “neutral” funds rate was (who is?), it was certainly a lot lower than where we are now. You might even choose to quantify a gesture; I’d say his was in the 3% area.

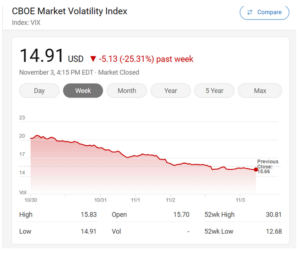

So, I feel like crisis-driven prices should not really apply. While the VIX? Down 25% in five days. Game over?

Search Results from MSN

Yanis, Right or Wrong?

Politically Yanis got lured by the old trap of supporting a party without a history, after sudden promotion, as a technocrat.

A rookie error.

But how does History see the Global Financial Crisis?

I looked at GDP from 2007 to 2022, for Bulgaria, Greece, France, Germany, UK, and the US. Here is the World Bank Chart of GDP growth rates. You can see Greece tumble out of the bundle, but it was also gathered back in, quite fast.

By 2007 the Eurozone was apparently out of control, spending was too high, it needed debt write downs, balanced budgets, selective privatisations and a war on tax evasion.

And Yanis felt Greece was being unfairly picked on to trial that medicine.

Size Counts

So, it is perhaps more instructive to look at levels, not growth rates. Here the damage is clearer, Greece has a GDP still substantially below the 2006 level. Bulgaria a neighbouring Balkan state, has doubled (and more) in the time. So Yanis has a point there.

Elsewhere France grew a shade faster than the UK, but from a slightly smaller base, so really little change.

But the US added almost twelve trillion dollars to its economy, which is like bolting on a new economy the size of the UK, France, Germany and Italy in just two decades.

We could adjust for currencies, population, different data points, calculation bases, of course and it is non-linear, inevitably. But we are looking big picture here.

Was The Left Right?

Gordon Brown was quite keen on the Yanis theory, and to some extent that adoration survived the subsequent dilettante Tory rule. Seizing big banks, attacking tax evasion at any cost, and aiming to balance budgets (Yanis was big on the primary surplus then) all crept into UK policy. The first two are oddly very non-Tory, especially when used to destroy economic growth by over-regulation. The third is quite sensible by comparison, but it was ignored.

Greece has since taken its medicine, with a steady swing to the Centre Right. Yanis finally lost his seat (for his new party) early this summer.

If the pain was indeed all inflicted to help the struggling IMF, no one told the US. If it was all done to save the Euro, I ask myself why did France go nowhere fast? It didn’t obviously hurt other Eastern European countries.

So, Greece remains an outlier, vastly reduced in wealth by the whole episode. It saved the Euro; it did not save Greece.

Where Next?

In the end, all national budgets work better with a growing economy, and in the long term that is essential. Flat or declining economies are the real crisis, especially without flat or declining state spending.

My highly selective period – (2007 being the pre-crash high) finds considerable upsides in both Trump and Biden’s expansion and in Obama’s reconstruction.

While if you need to know why the US stock market dominates in that period after the GFC, it is because GDP growth was twice that of Germany, and on course to double from 2007 quite soon.

Elephants can’t dance, they say, but when they do, the world shakes.

Insert Media here

Although Yanis, indeed has stopped making sense.

Charles Gillams

4.11.23

Sweet Dreams

Here we talk about the delights of the Conservative Party Conference in rainy Manchester, the failure of the in-built two-year time horizon in inflation models, and what may happen to interest rates.

FANTASY IN BLUE

At times in Manchester, it felt like everyone was looking for something. As government steps up spending initiatives, and empowers regional governance, and drives big spending on not achieving net zero, the chorus of demands for more taxpayers’ cash grew deafening.

There was utter silence on efficiency or capital allocation; it was all just “a good thing” to spend more.

And oddly too, with so much lip service to the long term and reducing debt and halving inflation, the ‘how’ of those was also ignored. Surely halving inflation is not even a government task? It was devolved to Bailey of the Bank - yet we heard not a word of criticism. If ever an eight-year commitment to a disastrously run project needed cancelling, his appointment looks to be just that.

This would spare him (and us) those endless letters on why he’s failing to control inflation.

For all that Conference was oddly cheerful - quite a bit of steel on show, from Suella of course, the only natural politician involved - some guts from Steve Barclay at Health, and Stride, a little less convincingly, at work and pensions - else, all rather wooden and on autocue. Although you could not help but notice that Farage still charms the fringe crowds.

COMPETENT DELIVERY?

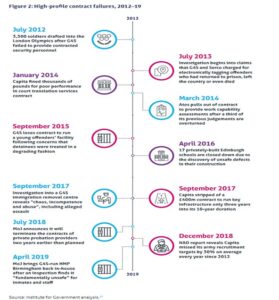

The abiding issue remains competent delivery. It was odd to hear the government on HS2 arguing for accountability by sacking their own Euston delivery team. As if the failure of HS2 is not theirs, and theirs alone.

Instead of penny packet incrementalism, government needs a holistic delivery view - perhaps why France can build a TGV, and we simply cannot.

From this report of the Institute for Government

From this report of the Institute for Government

The Maude/Osborne “reforms” destroyed half our domestic contractors, by a short-term focus and ceaselessly moving the goalposts. As a result, home grown firms are in the minority on the HS2 contractor list, and giant multinationals with more lawyers than bulldozers were the main bidders.

They want top dollar to take on the risk of a lazy, indecisive government machine - no wonder.

THE CHANGE PRIME MINISTER?

We have been very clear since 2019, that the Tories can’t win another term, none of that changes, but the scale and composition of the anti-Tory majority next year is rather less clear.

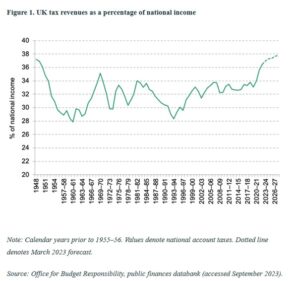

In many ways, the best case for a Labour defeat, at the next election, is that the Tories have done it all already. They have blown the bank on out-of-control spending, splurged on unaffordable welfare, and raised taxes to unsustainable levels.

From this website

From this website

This government also crashed the pound, let inflation loose, let rhetoric overtake sense and has gone in hock to foreign debtors. I suppose they have yet to invade a sovereign country without a UN mandate, but they are working on that too.

So? Well oddly Starmer is still slightly boxed in, and in terms of polling data, not really getting much help from the weak Lib Dems, in those critical three-way marginals in the South. While Scotland clearly has had enough of the SNP running Scotland, it is less clear that they don’t want the cause of independence to be heard in London. The Rutherglen by-election could be sending both messages, but in a general election voters only send one. I would not assume that genie is back in the bottle just yet.

JITTERBUG BLUES

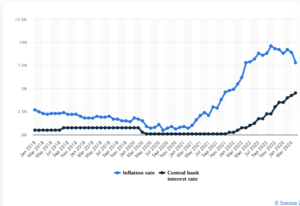

We continue to see US rates above inflation, which is very different from UK rates which are still below.

So exactly what Powell (and Bailey) are doing with selling down the Central Banks balance sheets at a time of maximum new issuance, is not clear; it solidifies vast paper losses, creates new losses on the rest, so seems to be quite a pricey warning shot to politicians. But it is a plausible reason (along with super high levels of new issuance) for current bond market nerves.

We have always felt the Central Bank models, where whatever the question the answer is “it will be fine in two years” are a fiction. The awareness that rates and inflation are staying high, is long overdue. But we have been in no doubt about it, for two years, nor have we ever flinched in our aversion to bonds, we were never being paid enough for the risk.

The jitters in the bond market feel more like a turning point, the sudden chop as the tide turns. The dollar has risen; people want to be there; if there is enough demand, that will lower bond yields again. So, I am not looking at US rates rising, so much as at the battle switching back to fiscal policy. Although in the end if Biden really wants 7% rates, I guess he can try to have them.

The UK and Europe are less contested, the labour market in Europe at least is not that tight, although still at record low unemployment levels, but with a lot of surplus workers in France, Spain, and Italy, and especially amongst the young. Euro interest rates are also really quite low still and are not yet looking restrictive.

So, it looks like another round of softening currencies, stagnant inflation and rate rise pressure. Central Banks still hope they have done enough. Even so it is quite odd that UK long rates are only just touching the level of a year ago, logically they should be two points higher. As for oil, we have seen this autumnal spike as a little surprising but transient, and as ever at this time of year, the short-term path is weather related.

Overall if the start is any guide, October yet again could be rough for markets, but longer term still looks brighter.

JENSEITS VON GUT UND BOSE

We ponder the point of the UK markets, ignore clashing BRICs, set up for the slow fall in interest rates in 2024, yes, long lags are long.

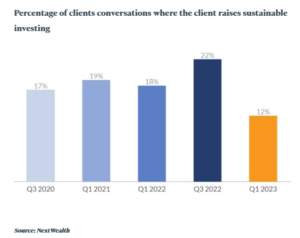

There are two investor markets, one akin to gambling and speculation, one allocating capital efficiently to invest capital or fund governments. But like weeds in a nutrient rich field, spare liquidity attracts the rankest growth of useless vegetation. There’s no clear way of knowing which is which. Money famously does not smell, and clients don’t really care much about how they earn a return, whatever they may say.

From: The FT Adviser Website

Fads and fashions in investing fuel some success at first - then they can no longer conquer new lands, and deflate, dragging down asset values as they go.

ARE INDIVIDUAL UK STOCKS WORTHWHILE?

I look back, as all investors should from time to time, at my successes and failures. Luckily out and out failures are pretty rare, and in some measure, so are successes, as I quickly milk the wins (usually from takeover bids), so they disappear from the record.

This leaves me a pretty solid mass of fairly dull UK equity holdings, I slightly favour value over growth. So, I know a simple snapshot won’t reveal the steady benefit of, at times, decades of good dividends.

But at the end of it all, for a UK investor, what remains is a mass of general mediocrity. Resource stocks have been good to me, still are, but the mass of industrials? Not really.

Or property companies?

Well big dividends from REITS, but again not really. Of financials? Again, long years of high dividends, but capital values stay scarred by the GFC. Chemicals, retailers, distributors, tech, utilities: well, all fascinating, with some good runs, often good yields. But in the end?

I could ignore such perennial plodders when their yields were far above base rate, but they are now surpassed, by a simple savings account.

So, I do wonder at times like this, why I hold them. Doubtless we will get rallies, but the tone feels a tad discouraging just now. And I sense the politicians of all hues, who seem to be eager to relieve me of anything that looks like a nominal gain, or enforce their often extreme views on my assets.

PERHAPS OTHERS DO IT BETTER

My long-term winners by and large stack up in investment companies, with specialist fund managers, and almost entirely overseas, or at the very least global. Not that is much of a surprise, we have mentioned before how the FTSE100 has not moved much in twenty, going on twenty-five years. Yet again it has flattered to deceive this year, yet again it has that slumping dinosaur feel to the graph.

The UK is not alone in that. Most of Western Europe shares that fate, and Eastern European investing has been a good way to create losses. Somehow Europe’s governments have done just enough to keep investing alive - and somehow the stock markets have had just enough liquidity to avoid collapse.

It is partly why so many investors love small companies, but they are savagely cyclical, as we are seeing just now.

I could blame management, and their apparently limitless greed, but while many quoted boards maybe have rogues or knaves, but nigh on all of them? No, I won’t accept that.

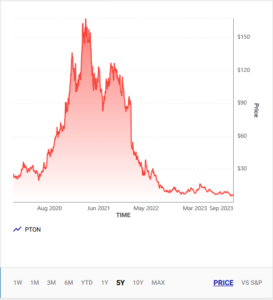

Globalization has freed capital to move easily and fast. Far faster than any real business can adjust, and in this world the ability to attract capital is vital. True many attract it, to waste it, like a meme stock, or Peloton, but it would be wrong to see that as a line of tricksters repeatedly finding ways to con the market (although many have) more about the power of liquidity to inflate prices, attract buyers, inflate prices once more, in an unending climb. That is until the last buyer has paid up, and the tipping point is reached.

Taken from this website

Then the whole thing unwinds downwards, down to a true value, or less.

WHERE NOW?

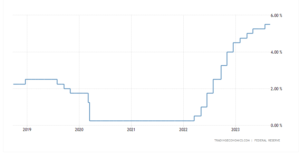

On the one hand, as interest rates fall, and they will do soon, even if that one last hike is much discussed and may well happen, the path looking forward is downwards.

FED rates in the last 5 years

This should benefit value stocks, as more and more dividends emerge once more above the high-water line of cash deposits. Rates won’t go all the way back to zero, that is gone, but should start on the way down.

On the other hand, the liquidity trade is here to stay, money attracts money until the thermal tops out and the vultures glide along to the next spiral, or indeed back to the last one.

And looking over decades, as fund managers must, that is all that happens in most markets globally, one or two have true secular growth that also gets returned to investors (a key caveat), most seem not to. Investors become either hobbyists in love with a stock or short-term traders. It is notable how many of the new breed of big company directors spurn the shares of their own companies, bar a token few thousand.

Markets seem to have progressively been made easier for momentum, versus ‘true’ investors, allocating capital to create real jobs. The capital allocation bit is worthy but dull, and arguably governments and regulators seem to have strangled it into stasis.

The endless, joyful, mindless dance of momentum, is simpler, prettier, easier to tax, cheaper to trade; quite wonderful really. But is it much else besides that, or is it substance without meaning?

It is odd how governments moan about the lack of growth and yet cripple capital allocation. In a market system, the best capital allocator wins. It is really quite simple.

Once the tightening stops, there should be more currency stability (of sorts) as all the Central Banks realign their rate patterns again. In (to us) an unresolved month, the dollar’s strength has been notable, when not a lot else was.

It is Not a Pipe

A long view this time : Has the price of capital changed for good? How bad is the UK position? Oh, and the unusual universality of colonialism.

A Far Off Galaxy

Let’s start with colonialism. I have been reading about the benighted past of Bulgaria (R.J. Crampton, 2nd Ed, CUP). A Bulgarian I know said that the country ‘has a knack for picking the wrong side’ - a little harsh, I thought. However, it has always existed as a colony, aside from a brief imperial phase around the last millennium but one, and before that when it equated to Thrace, almost as far back again.

Given the option, Bulgaria recently opted to join the Western European empires’ current formulation as the EU and NATO - the latter being the armed wing of Western thought. Bulgaria had suffered horribly under the Soviets, with a steady and ruthless coercion of an existing multiparty democracy, at a speed just enough to keep outsiders ignorant, or if not, passive.

That history gives me a whole new viewpoint, on the string of broadly similar states. The Balkans and The Middle East all appear in a new light, and indeed I start to comprehend the bitter sideshows (as they seem now) in both World Wars, over that same terrain.

The collapsing empires (Russian, Ottoman, Roman,) seem more influential than the current rulers in so many former colonial states. They are really not, as we think now, a series of nations fighting for ‘independence’. In most cases that independence is fragile to the point of being mythical, while the internal fissures are enduring. The cracks of nations within empires, not of states within a world.

Now You See It

One passage in Crampton’s work stood out “by mid-summer social and industrial unrest were widespread with strikes by civil servants. On transport networks, and despite the provisions of the law, in the ports and medical services. The government was forced to grant a 26% wage increase to all state employees, an action which weakened its attempts to control the budget deficit and inflation and which did little to impress the international financial organisations.”

Written about conditions just before another wrenching Balkan realignment last century, this rather made me stop and reflect.

A parallel with the UK?

Just how close are we in the UK to that edge? Lost in a warm feeling for individual strikers and their causes, and a very British willingness just to plough on, there still seems to be a real danger.

I am well aware of our great national strengths, in the arts, our language, higher education, science, heritage, even logistics and retailing - they are enduring causes for optimism. But long-term investors need to weigh up the recent damage, especially the loss of political capital by the “responsible” right, the high levels of debt and taxation, which coupled with low productivity, could also spell trouble, the certainty of ongoing nationalism and the unhealed rift of Brexit.

There is danger too in the probability of a Labour government, which however centrist the leader is, will have left wing factions to assuage. It is equally dangerous to continue our recent experience of minimal ministerial experience. I hope the change won’t be as bad as I fear, but it will probably be worse than I hope.

This remains a reason for the FTSE to be anchored to late 20th Century levels, despite almost every stock I research looking cheap. The fear of being still cheaper tomorrow rules.

Do Markets Care?

On the other hand, re-pricing capitalism after the decade of populist nonsense by central bankers does feel pretty good. If you have no cost of money and no reward for savers, financial gambling prevails.

All of this raises a key issue: is the apparent resurgence of speculation (the greater fool theory of investing) permanent? In which case investors should probably just watch momentum. Or is this most recent re-run of the last decade’s speculative phase, really transient?

For a better view, see this page on Statista

As long as inflation exceeds the cost of money, assets will likely rise; the widespread return of real interest rates (a point we are almost at) should slow that down.

After that point what matters is cash flow, and whereas gambling will favour growth stocks, real returns come about when interest rates are high, but inflation is also falling. The gap matters and we are not there yet.

This is probably the crux of the next two years, and we doubt that having had a serene and slow drift towards recession, there is any reason either to expect a suddenly faster descent now, or really to expect the corollary, a sudden fall in interest rates, to offset a deep recession.

If rates stay high, but have indeed peaked and inflation declines, value investors should be in a better place. If they get it wrong, they are at least paid to wait.

As we have seen in the last twelve months, growth investors fuelled by borrowed money really do need a rising market, they get hit twice if it falls: both through a loss of capital and then the need to fund loss-making assets at real rates.

The Monogram View

Overall, our position has been that fundamentals should win, but we suspect momentum will win. Spotting the next momentum shift early, therefore remains a powerful driver of returns.

One narrative of 2023 (so far) is that the SVB crisis and stronger growth combined led to far more liquidity than markets expected. This fed into the gambling stocks, giving them momentum.

So, although the first half was not what we expected, the second half might still be. But it is just one narrative, and it may still be the wrong one.

Note : Further reading, for those interested in Bulgaria :

See also, The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo-Manichaeism, Obolensky, Dmitri.

Skipping along

Skipping is the week’s theme, following the inadvertent use of the term by the Fed Chairman, along with the rather weird behaviour of Jeremy Hunt.

Although any skipping seems unlikely soon, on this side of the Atlantic.

The dear old ‘recession’ still lingers, unseen but feared, like an ex Prime Minister. We are convinced it will arrive, but as a ‘technical’ recession only. It should be hard for anyone to be surprised. Labour markets are much stickier and far more fragmented. Supply is short, so any systemic shock feels unlikely. While as old hands keep noting, single figure mortgage rates, well below inflation rates, are hardly restrictive.

Chair Powell (almost) mentions ‘skipping’.

Jerome Powell was bowling along contentedly, when he suddenly described the Reserve Board’s June inactivity as ‘skipping’. Although it actually was just a ‘skip’, before he realised the error and with a guilty look speedily reverted to the far more passive ‘pausing’. But we knew how he was thinking. He was going to keep his foot on the neck of borrowers for a bit longer – interestingly, he refers to real rates of interest, as somehow unjust and injurious. Odd that when asked anything about fiscal policy he instantly plays the neutral, technical banker, no good and evil there.

Moves in the real economy.

So, what has really happened?

Not a lot, energy prices have climbed all the way up, and now slid all the way down. Aggressive fiscal stimulus continues, any chance Biden has to bribe the electorate with their own money, he still takes. Employment remains strong, although there is some tightening in hours worked, but it is still pretty hard to see how the Fed gets down to 2% inflation for a year or two.

And yet, markets by a mix of that unseen recession and faith in so called base effects, do think inflation by the autumn, will justify a real pause. No skipping.

UK Chancellor’s odd statements

Here in the UK Jeremy Hunt is in quite a different place. Inflation still looks high and embedded, but he has carefully outlined how he would keep going with substantial hand outs to offset inflation (aka fiscal stimulus).

However, inflation control was all for the Bank to sort out.

This is nonsense, of course. The UK Government is yet again stoking inflation while taking no responsibility for stopping it. He then gave a tortuous explanation as to why his policies have now produced exactly the same interest rates as the Truss typhoon, created by his reckless predecessor, but somehow, not at all the same.

Rate rises – a global feature.

Funny that, as we noted at the time, there was little odd about the October rate spike, and much that the Bank could have done (but refused to) by a prompt rate rise (matching the US) to stabilise the currency and inflation.

Rate rises are a global feature, with not a lot one small country could do about it.

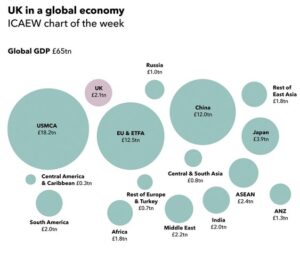

2021 chart produced by the UK Institute of Chartered Accountants

So quite where the virtue of the Truss toppling quarter point rise is now, is rather unclear.

As sterling shows, the prize for that autumnal sloth will be higher rates (and inflation) than elsewhere for longer. The thing about fire fighting is the sooner you start the less you have to do.

So how did Monogram’s methodology work?

Our in-house model switched into Japan in December 2022 and Europe in March 2023. As we only ever deal in half a dozen big global index Exchange Traded Funds, this is not a tickle, but 25% of the total equity position in (or out) at once.

Brutal and scary, but effective.

We look at the signal, kick the tyres, thump the bonnet, turn it off and on again, look for reasons to ignore it, and then six months later look back in wonder and say, “oh yes, that was right”. These signals are delicate enough to very seldom feel right at the time, but after almost a decade of running the model, we have learnt to obey.

So, our Momentum performance discussion, yet again, is about how much we made, not about in which direction the money went. While the GBP version, seeing similar signals, has also never come out of the S&P 500, which for a good while also felt wrong, but it seems was right, taking a long view. The USD model was more skittish but is back in both (S&P and NASDAQ) US indices now.

So, we do know where momentum has been, and it is quite strong.

Markets in the political timeline

The rational thinkers say the market is (still) too expensive, but the trend followers don’t agree, who is right?

We tend to feel just as Central Bankers were very slow to spot inflation, they are possibly being too slow to see it has now been contained, and the US skip may be a pause and then a snooze. Which would be very convenient for the Fed during the US Primaries, allowing for cuts into the US election?

Related to that, we watch with amusement a dialogue about the attractiveness of stock exchanges, in particular in London, couched entirely in terms of what potential listing companies say they want. Not a mention of what investors want, as if they just don’t matter. Quite absurd, as what all listings need is a deep market, good liquidity, stable tax regimes, and an attractive base currency.

Is London aiming to provide these? We seem to favour founders – so, tweaks to voting rights, smaller free floats, fewer shareholder rights. But then oops! No buyers.

This is worse than nonsense, it damages what little is left of London’s reputation. In this market you start with the buyers. The price performance of many a recent IPO spells out the problem, the sellers are finding it too easy to deceive people – a call is needed for greater transparency, longer lock-ins, and less pandering to insiders and their advisers (not more).