Pain delayed, pleasure denied

June 4, 2023investments,UK politics,valuationsUK,investment markets,Economy

We look at the startling emergence of another US based tech bubble, the failure of value investing and offer some reflections on the UK market.

The Bones of World Financial Markets.

This has been a baffling half year in which, with few exceptions, we have ended up going sideways for most of it. The exceptions were in descending order, within equities, the NASDAQ (by a mile), Japan, Germany, the S&P and France. Although all, especially Japan, offset by a weakening local currency for UK investors. A quite unusual, largely unrelated, mix of old and new.

Overall, cyclicals in general, and energy in particular, as well as bonds, and China have been painful and financials at best so-so. It feels like a year to not hold what worked last year and vice versa. Nor is it as simple as growth versus value; neither have worked consistently, except in the case of a small (but rotating) group of tech stocks.

Our view thus far, has been that until global growth starts to move, we stay out of the way. This has been wrong, because the overvalued US mega stocks, were almost the only game in town. Yet jumping in now, of course, also feels very dangerous.

However, a few of our growth markers have, even if flat on the year, started to shift, not the highly speculative micro stuff, which is still falling away, but the solid middle ground. The hot India tech sector, far more connected to Silicon Valley than we realise, has suddenly jumped.

Macro Skeleton

What about the underlying macro story? Well, the pain of the invisible recession, and the pleasure of resulting rate cuts, have been delayed and denied respectively.

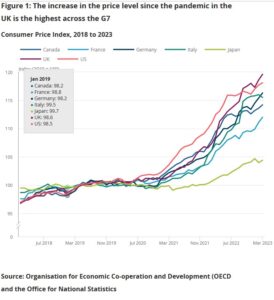

From the UK office of National Statistics – see this chart more clearly on this page.

From the UK office of National Statistics – see this chart more clearly on this page.

Well, there it is, poorly controlled inflation persists, a longer rate squeeze may still be needed. The vanishing China post-lockdown boom means that there was no sudden stimulus to offset that. Our published data (from Andrew Hunt) was saying Chinese ports were remarkably empty three months ago, from soft export demand, a good lead indicator.

All of that was hidden by strong services demand, and in closed economies (as the UK is oddly becoming) there is no relief valve, and hence it suffers embedded high inflation. But clearly consumption is dropping in the US, recent retailer numbers are all over the place, confirming those China export stats.

While on commodities, the failure of sanctions to impact energy is ever more clear, and I doubt OPEC’s ability to stem the energy glut. As a final blow to value stocks, “higher for longer”, on interest rates, which we have been predicting for two years, hurts indebted companies, who increasingly have to refinance at high rates. It also makes their dividend yields less attractive.

When rate cuts do come, growth having survived the storm, may well soar; as we have noted before, the prevailing fashion in investing heavily favours so called “tech moats” and dislikes debt. That markets keep seeking out new moats, real or imagined, is all part of that.

The speed at which digital currency and virtual reality have become old jokes, but generative AI will save us all, is remarkable.

Bond Dilemmas

In bonds we have seen no point in our lending to governments at rates that are below inflation; in most of the world as inflation falls, bonds still remain unattractive, as yields then start to drop too. So, the bond trade has been messy to say the least.

With greater certainty about a consumption recession, the fear of defaults also rises, and the longer rates are high, the more that refinance risk looms. Jumping a spike is possible, vaulting a table, without spilling your drinks, rather less so.

There is also still a ton of money parked up in fixed interest, just waiting for the equity ‘all clear’.

Lost London?

The UK market (yet again) simply flattered to deceive; I struggle to see much hope for it. While we can hope the likely change of government will be an enhancement, it really will just entrench welfare dependency and producer capture of state services, albeit in a rather more disciplined way.

The risk of Brexit always was that we would use our new freedom to rebuild old prisons. Can a new flag on an old workhouse change much? As for where our stunningly high inflation comes from, again, it must be our own creation, the Ukraine energy peak is now a dip, so it is not imported.

While no one wants to say it, tax rises, especially of such magnitude of corporation tax, in particular, are inflationary, but so is the cheap theft of frozen income tax thresholds. Trade unions employ good economists too, they negotiate for higher take home pay. Rate rises also cause extra inflation, especially with our persistent high national and consumer debt levels.

Sterling strength (it is now moving up against the Euro too) is a sign of markets seeing the UK as the best bet for avoiding rate cuts (and for getting more rate rises). That is not a good sign domestically.

Small Earthquake

May 18, 2023scottish companies,pensions,corporate culture,valuationsOpinion,private equity,investment markets,UK

Full year corporate accounts have now all been published, in several cases even read, so it is time to look at the raw data beneath all those clever funds and derivatives, at the underlying companies.

There are two themes emerging: one is the extraordinary scale of movements last year in defined benefit pension assets and liabilities, and the other is how we should evaluate the size of the Scottish discount.

Pension Asteroids Collide

Enormous numbers are shifting on defined benefit pension schemes, nearly all the big ones seeing asset losses of several billion, but with matched declines in liabilities of the same scale, leaving almost no apparent change, all stitched back together. This impacts in particular the big banks, utilities, resource majors and of course life companies.

It is a source of some nervousness, when large numbers crash about the balance sheet, dwarfing the trivial numbers in the profit and loss account. But they are also quite different items, the asset declines (from long dated gilts) are real money, stuff you could have woken up at the start of the year, picked up a phone and sold.

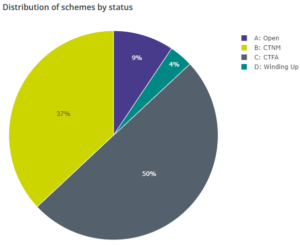

Yet the liabilities in terms of actual money to retirees hardly shifted, it was just discounted differently. While nearly all (91%) of the 5,000 odd UK schemes are either Closed To new members (CTNM) or to future accruals (CTFA). So, of little current relevance to operations.

From: This page on the UK Regulator’s website – the key to the abbreviations is also there.

What is relevant is the sudden loss of tens of billions of pounds ny these pension funds. But that is ignored, because of the liability offset, but it was lost and is gone. This came along with dramatic changes in the value of the gilts they hold, in cases by more than the unit value decline, as gilts were actually being sold quite hard too - a big chunk of assets that no longer exists.

Scottish Exceptionalism

So, to the Scottish discount. What is it? In our valuation models we discount earnings for political and operational risks, including for governance, including the location of the auditors. It is an internal assessment, so matters not a jot, unless others do the same.

We know the discount exists, the reversing tide of “swimmers” or companies raising money outside their domestic market, tells you the entire UK is already at a fair old discount to the US, even for companies with mainly US earnings. Should the same apply to Scotland? And by how much more? 20%? Whatever it is, it is getting bigger for us.

In my view if you are a FTSE100 Company, you have big four auditors, London office. Regional offices and smaller firms will be more dependent on a single big client and in enough cases to matter, that disproportionate power will swing it, for the Board, against the investors. Not that London based Big 4 is perfect (we know they are not).

So, to Scotland, there is a long-standing assumption they will use Scottish audit offices, and a drift to using Scottish firms too. This used to mean high quality, but I now sense they lack experience. Boards have also increasingly become reliant on a smaller pool of candidates, and two recent high-profile cases leave me wondering about their governance.

1. Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust

We sounded the alarm on the peculiarities of this popular fund two years or so ago, in their glory days. Like some other troubled funds, they took on more and more unquoted holdings. All disclosed and approved, but in the end clearly linking private and public markets, indeed boasting of how many of their quoted holdings started out as private ones. Well, a closed IPO market knocks that bet pretty hard. When a lot of them are also Chinese, that renders that pipeline even more suspect.

While disclosed, yes, but adequately disclosed? In one case they hold G, I, H, A, C, B Prefs and A Common Stock, with greatly varying valuations by class. We were nervous, when the share price failed to discount these holdings, at a time when other equity trusts, indeed private equity specialists, were facing growing discounts on their holdings.

That has now corrected, the Board has finally stood up to the manager and questioned the existence of the in-house skills to back up these valuations. But in the process our Scottish discount opened up.

From a three year high of over £14 per share, SMIT has fallen hard to just over £6, wiping out half the value or the thick end of £10bn, from presumably mainly UK retail holders. It has kept falling. I think it will need to list those unquoteds separately, and give holders a share in each asset pool, to regain its once illustrious crown.

2. John Wood Group

The John Wood Group, which operates in natural resource consulting and contracting, has been a disastrous investment. A well-respected consulting firm, its Board decided to merge with another well-respected quoted consulting firm, Amec: outcome? Hugely negative. Five years ago, its shares were over £5 and even quite recently shareholders were hoping a private equity bid would rescue them after only a 50% loss.

But having overseen that catastrophe, the Board seemed not to be listening. They only very reluctantly agreed to bid talks, and somewhere in those talks something persuaded the bidder to back off. From the bid inspired high of £2.55, it has now virtually halved again. The Board feels old style, out of date, insular. I particularly enjoyed (it is one of the few pleasures of reading so much verbiage) their illustration for the diversity report, (see below).

Extracted via screenshot from the Annual Report and Accounts of the John Wood Group

This reminded me of sitting on a School Curriculum Committee (see the fun I have). We had to cover multiculturism, and the teacher (in the high pale Cotswolds) chose India; intrigued I asked why? The answer was that allowed the topic to be covered for our forthcoming Ofsted inspection, by having a takeaway meal in class. That was it. No map, no history, no people, just an affiliated consumable.

But nice money for the executives, look at last year’s bonus structure. That odd picture served them well. For an original business that is now itself worth nothing and half of what it paid for Amec !

Now, but for that Board, or that history, Wood looks a nice business, cleaned up, $5 billion of apparently profitable sales, with a market cap of £1 billion, not a lot of debt, all three divisions profitable at least at the EBITDA line. Heavily exposed to renewables, including in North America, it even reports in dollars. You could argue the bid was low - no doubt the Board did - but if the price then halves, after the bid vanishes, how credible are they?

So, in comes the Scottish discount – because this pattern of behaviour speaks of a particular culture and leaves me feeling the need for a bigger safety margin, to buy a business from that region.

The Long Recessional

May 7, 2023UK Politics,Central Banks

English local elections, and US regional banks

The English local elections saw the Tories lose 1,058 seats, dropping to 2,299 in the wards contested on Thursday, Labour gained 536 rising to 2,674, while the minor parties saw the Liberal Democrats rise by 405 to 1,626, Independents dropped by 104 to 962, Greens rose by 241 to 481.

What does all that mean for next year? Well, we called the next General Election for Labour the day after the results of the last one, and nothing has changed that view. Nor do we believe talk of falling short of an absolute majority is anything but wishful thinking by bored commentators. Rishi is largely in office, but not in government: a fairly weak cipher for the mandarins behind the throne. When they tell him to abandon core Tory principles, he obeys. This divides his party even further.

So, investors really should focus on the ‘what’; not the ‘if’. The Tories as we noted last time, had most to lose, and will take some heart at the spread of their defeats amongst the opposition parties. Although given the locations contested, both official Labour, and the Corbynite rump voting Green, did well.

This was an anti-Tory vote, rather than pro anything in particular.

We will still see a solid Labour governing majority next year. The Lib Dems will likely be back over fifty seats; as ever un-representative of their larger vote share.

So, what of Starmer?

His big offer is that he will stop party infighting and provide stable competent government. It will be Blair redux. The core five aims are currently crime, education, NHS, climate change and growth. Who would have guessed. No doubt apple pie is next.

The method it seems is Blairite targeting, with a bit of management mumbo-jumbo about breaking down silos, overarching aims etc. With the one area of large-scale Soviet style planning in the energy sector, with a state-run organisation, with what sounds like loads of money, but in truth (for the task) is not. Anyway, the big issue is not power generation but transmission.

I guess we do know from Wes Streeting, (the next health minister) that Labour knows the real problem is the public sector unions, part of why Starmer was so keen not to rely on their funding or support. But while ‘silo breaking’ is neat code for curing chronic demarcation fights, again, how does he propose to tackle it? Breaking ossified crusts needs steel. We know soft soap and water won’t do it.

But to tackle that, means splitting up some giant empires and even if Labour wanted to, I doubt if it has the means. At the same time public sector reform requires exiting vast areas where mission creep has expanded a thin film of under-funded interference and sub-par delivery. True Blair did cut loose Scotland and Wales, to wreck their own patches, raise their own taxes, maybe we will see more of that?

So, we should not hope for too much, we will get another well-meaning ambitious left-wing lawyer, but he is not Blair, and Blair despite fond memories, still gave us the GFC and Iraq.

We fear that the hostility to business and enterprise shown by Sunak will persist, it is probably embedded in the Treasury and Whitehall.

The slew of rate rises, and the slow sacrifice of the US Regional Banks

Somehow Wall Street keeps looking for rate cuts, and collapsing inflation, when it is simply not visible in the data. They are so hidebound by their models, that they see inflation as a pile of bricks. You count the bricks; you know what inflation is. But it has never been that, it is like the water table, it is a level, not discrete pieces, and like water it spreads, dampness pervades all. Sure, you can remove bricks, even big pieces of wall, but the water table needs everything to dry up for it to subside.

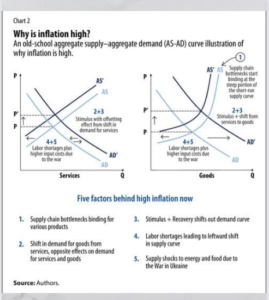

Taken from this article by IMF staff writers, Agarwal and Kimball in 2022.

You can see the flaws, factors 1, 2 and 5 look like classic bricks, or transitory bricks we should call them now. As for 4 that has been entrenched by regulations, especially on minimum wages, by tax hikes, health fears and support payments, which leaves 3 as the real solvable problem, and it endures. True they rightly noticed it, but by relying too much on the bricks falling, institutional economics just keeps getting it wrong.

You can’t lower the level, while demand remains too strong to be drained away. While the idea you can disperse inflation while piping liquidity in to offset the cost-of-living crisis, is simply daft. Until excess fiscal stimulus stops, inflation will quietly shift, steam away, reform, and then drip back on us; clammy and damp as an English spring.

It helps a bit that vacancies per job seeker are falling in the US, but it is all pretty glacial, the job market is still very tight and wage inflation still embedded. We are awfully short of swallows to be declaring summer’s arrival.

Yet, we do accept Central Banks have largely given up on rate rises, we think too soon, and their main mechanism will now be leaving rates elevated for longer. Along with quantitative tightening, which as few politicians really understand it, they can get away with. Well, it may slowly work.

Looking ahead

We (still) see inflation as higher for longer, rates likewise, and over time the big users of debt, mortgage borrowers and national Treasuries, are going to get used to paying more for it.

Although expect some other fiddle to try to stop this too, which will, naturally, embed inflation and stagnate productivity.

Markets? Well, with plenty of liquidity still and indeed (unjustified) rate cut optimism and many cash flow yields staying attractive, they remain skittish, but with no panic.

So, we are not that gloomy. Although perhaps a sideways summer is ahead.

If your base case is rapid rate cuts and mean reversion, we still have our doubts.

Charles Gillams

Monogram Capital Management Ltd

The Recessional is a great poem by Rudyard Kipling. And the Long Recessional, the title of David Gilmour’s book on RK.

While Shonibare’s trademark mannequins rely on implausible inflation to prevent disaster too.

Wood for the trees

April 23, 2023bull market,UK politicsOpinion,UK Politics,investment markets,Economy

We have all been obsessed with rates and inflation, but we seem to be in danger of missing what looks like a widespread bull market running broadly from last October. This is widely applicable outside the main US markets, including in gold. There is a similar and at times masking trend of dollar weakness.

What are the implications of this?

We also look at the unending tragedy of the various remnants of the Tory party.

Still Rising?

With markets still fixated on the next crash, we can sometimes overlook the long momentum swings. Although the US banking crisis matters, it is of little relevance to the far more concentrated and tightly controlled Basel III banks in Europe. Many would say to excess, but they are clearly tighter rules. The few assets not marked to market are a footnote in Europe; in the Wild West of US regionals, they can be the whole story.

On a one-year basis, the France CAC 40 is up 14%, the German DAX by 12%, with both the UK large cap and Japan’s Nikkei also positive, so equity markets have been strong, almost regardless of rate rises. The US is the main home of negative twelve month returns, but the gap between the S&P and the NASDAQ declines over that period, is now quite small, after the spring bounce back in the latter.

What does that mean?

For all the media love of the disaffected trashing their own communes, doing the right thing on pensions (they were very out of step) apparently helps France.

While the splitting of power in the US Congress and the meanderings of a senile President, has perhaps hurt the US, with everything from banking regulation to the debt ceiling made into a political game.

Brazil is down too, but India and Russia are up.

Well perhaps I go too far, but maybe there is a pattern? Markets like stability.

Relative values

While comparisons are complex where accounting systems diverge, the UK still looks like the lowest rated with the highest yield, and conversely the NASDAQ still has (by some way) the highest rating and lowest yield. US earnings are it seems still much more valuable.

The savagely anti-business stance of the UK, including a brutal rise in corporation tax maybe part of it, it will create a fall in earnings (and likely dividends) next year.

While the less visible, but still onerous onslaught in the US, including a minimum tax take, won’t be good.

So, does inflation matter?

The UK perhaps is also seen as the one major European market that looks to have dithered too long on controlling inflation (which could explain sterling strength). However, I see no real appetite for more austerity in the UK, so I find that assumption slightly puzzling. Having the FX market convinced UK rates are going a lot higher (because of policy failures) is hardly comfortable, but feels a little like re-living last year now.

Oddly too, controlling inflation the US way, has hurt equity markets more, it seems, than letting it burn out in the European style. Heresy to many of us, but that’s what the numbers imply.

All the theory, all the historic data says we now must get a sharp recession, but then grandpa, pray where is your beloved recession? Still looking, since mid February. It seems we must appease the inverted yield curve and believe base rates matter, but a bit more evidence would certainly help.

And rate cuts will be a powerful tonic, when they come. The bears are now reliant on widespread recessions, and soon.

Perhaps the best of this little bull market has gone, but there is a lot of liquidity still about and being out of the market with high inflation, is not great.

A multitude of sins – local elections coming up

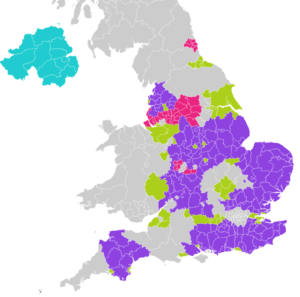

And what of the UK Tory “Party”, if such a mess can be called that. The assumption for a while has been that the imminent local elections will be bad for them. However, they are a curious mix of voting locations this time, not London, not all of the Home Counties, none of the Celtic fringe, but a good chunk (but again not all) of the Red Wall seats. See map below.

Map from Wikipedia page on 2023 local elections

But really it is heavily biased to the Tory heartland, vast swathes of Labour free wards, where they are not even bothering with candidates, so it will not tell us that much. The Lib Dems will do well, but significant conquests in many areas will now require quite substantial swings.

The assumption is also that Dominic Raab was cut down by Sunak, who has yet to learn that throwing competent colleagues under the bus may feel good, but it thins the ranks of effective ministers, and builds up the malcontents. He has handled these badly, and forgets the real target is not his ministers, but his own position.

Tory strategy

Seemingly the Tory party has run just one electoral strategy for years, based on old victories; just trash the opponent. In a two-party state, voters must then decide who they dislike least. And both Labour (and the SNP) have reliably offered something so vile, that a simple victory follows.

But no longer, Labour (despite their recent rather crude posters) still seem innocuous.

The Lib Dems are sticking to their amateur politics, which can also look strangely alluring, if the other two parties look mysterious or inept. The Tories (like the SNP) are now in danger of being judged by results, not by fear or hatred of the alternative.

The score card on that basis looks pretty bad, and Sunak’s pledges are so far, going the wrong way.

The Sleep of Reason

April 2, 2023US Dollar,regulation,investments,banksEconomy,regulation,investment markets

Big picture risk assessments today, and worries about the prevailing style of regulation - we look at where the next bank blow up maybe. We’re assuming this will again be caused by regulators and their herding behaviour. On the upside, an improving medium-term market outlook. Also, dollar danger.

But before I begin…

First of all, many thanks to those who replied to our sentiment survey, you are a cautious crowd! Over half (53%) sitting on the fence, alongside us. The largest directional group is bullish on equities (18%), but it is a pretty even bull/bear split with bonds, and quite a few equity bears too.

Regulatory Myopia and Declining Banks

Bank boards (and auditors) are still clearly confusing regulatory approval with sound banking, in the odd belief that excuse will wash, when they implode. In particular we worry about the vast amount of debt that is sitting on bank balance sheets, at below current market levels, and not in this case issued by governments.

We have notable anxiety about two areas, fixed rate mortgages and investment grade debt where, especially for the former, the numbers are vast. Perhaps the tightening steps to date appear so ineffective, just because so much of this old low-cost issuance, is only very slowly rolling off .

Big picture – the effect of long dated low-cost loans, with rising interest rates

This leaves cheap money in the system, funded by banks, that have to pay way more to keep funding these long-term deals. They’re doing this typically with short-term sources, like deposits. In sub-prime, asset finance, trade finance, consumer finance, none of it matters much, as they are pretty short duration. Which is where most people worry, because of default rates, we don’t.

But in mortgages especially the regulator typically issues the future economic scenarios to banks, who then price (originate) and provide for losses against that projection.

If that projection is absurdly few rate rises, for a decade (as it was till fairly recently), it seems banks just follow obediently along. As a result, they have issued vast amounts of long dated, low cost loans based on false or unrealistic assumptions.

Those regulator driven economic assumptions/scenarios are key, and yet are lost in the detail. Each bank has to publish them if you dig deep enough. (Some are on p155-157 of the HSBC accounts, for example, if you have the stamina.)

Re-mortgages – what they contribute to our big picture

The other part is refresh rates, in a falling interest rate world, borrowers re-mortgage every few years, but in a rising one early redemptions virtually stop. So, the whole system gums up, without fresh liquidity. Regulators have not seen, and have no data, on such a ‘higher rates for longer’ world. So, it is assumed that world cannot exist. While the key thing (still) on these scenarios is that interest rates are still assumed to be like rockets, straight up straight down.

Now if you assume that, there is some short term pain, but normal service resumes soon enough with no long-term issue. But is it realistic? It is a vast slow moving market as in this publication of the FCA’s mortgage lending statistics .

Inevitably the scenario dispersion used is small, indicating a regulatory finger remains on the scales. So, most banks take the Central Bank forecast as the middle way, with say 10% either side. All as at the historic balance sheet date. Last year they were nonsense even before publication, two months on.

That is aside from Hong Kong, where real economic models, with real outcome ranges are visible. For most markets you see a skein of twisted rope drifting laconically into the future, but on HK they produce an exploding ammunition graph, smoke trails looping everywhere.

To a lesser extent BP debt (a classic investment grade, big, global borrower) is a similar problem. It has half fixed, half floating issuance, but the fixed is at 3% with a fourteen-year average term and the floating at twice that, at 6%. Now someone holds that fixed debt, and if regulated it will have to now be held below par. Are BP going to prepay it? Despite the roar of cash coming in, why would they? It is stuck, unusable for 14 years, unless inflation (and rates) collapse as fast as predicted.

What else is driving markets?

The big upside drivers to us are, the end of COVID, the end of the energy spike and falling rates. The first two will help through 2023 and 2024. Rising rates are still hurting, but again 2024 and beyond looks good.

While the biggest current downside driver is the recession, which will impact 2023, but again rebound in 2024. So, the issue is: will the rather timorous monetary tightening and anaemic reductions in the absurd fiscal overdrive, be enough to defuse all that good news coming in the next year?

Markets apparently think not.

We are particularly struck by the NASDAQ up 18% year to date, yet our tech bell weather share, Herald Investment Trust (HIT) is still (marginally) down YTD. So is this a bitcoin-type story (all about liquidity) or is it based on tech fundamentals? If the latter, then why is it seemingly glued to the US, and not translatable? Even failing to reach non-US holders of US companies.

For now, until the price of global tech shifts, I treat the US as a special case; growth is not back yet.

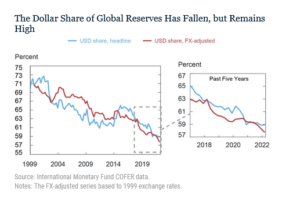

While the currency charts are unclear, it does also feel like the beginning of the end of the great dollar story, with sterling persistently ticking higher of late.

From: this page published by the NY federal reserve.

From: this page published by the NY federal reserve.

That’s a real danger for portfolios that thrived on dollar power last year.

We close wishing you a happy Easter break. We will be back with St George.